By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

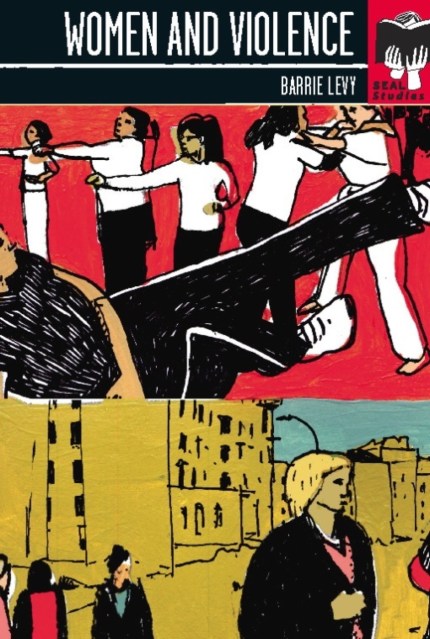

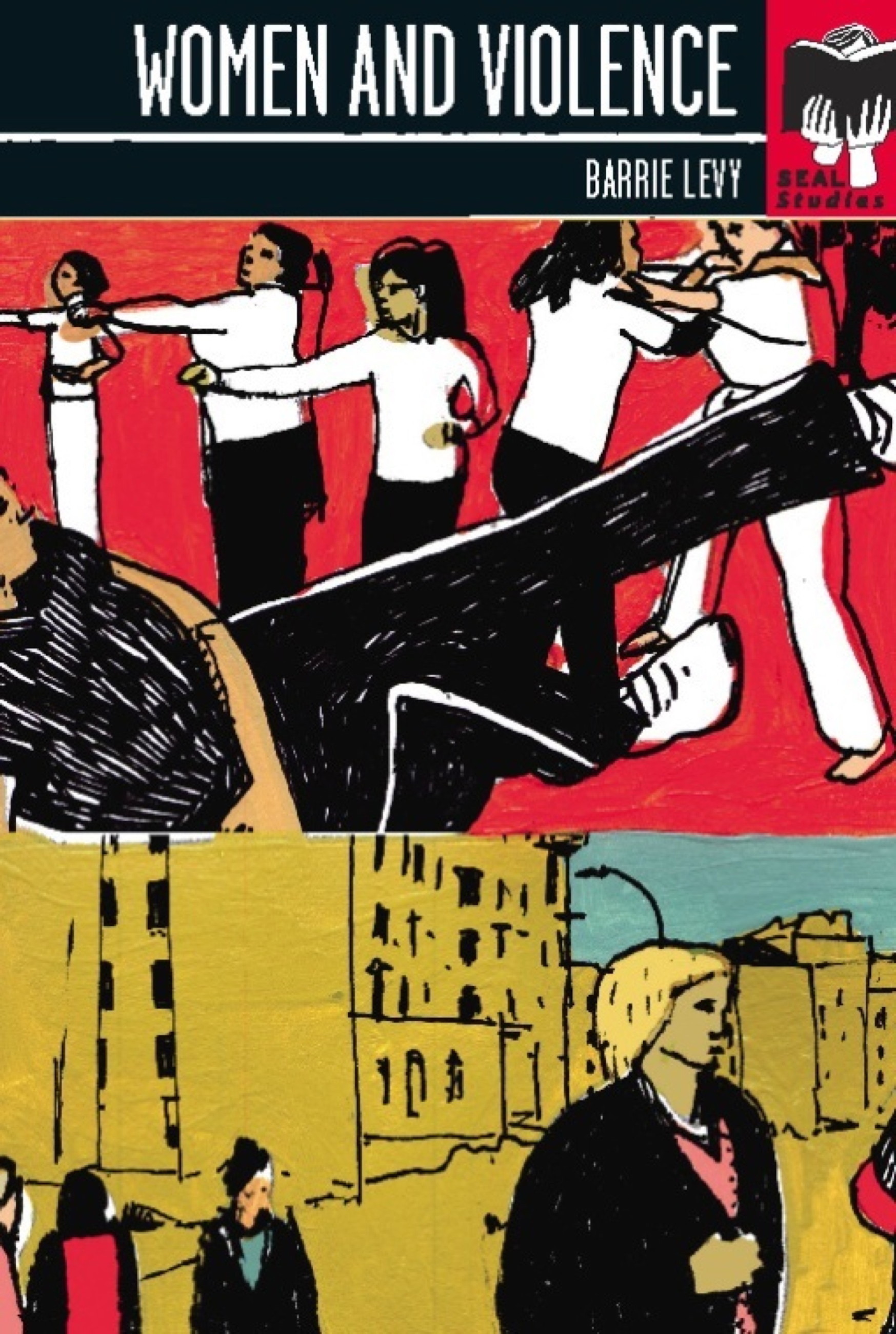

Women and Violence

Seal Studies

Contributors

By Barrie Levy

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 12, 2008

- Page Count

- 150 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786726721

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 12, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

When women decide what to wear, where to go, how to get there, what time of day to be outdoors, and what affects their sense of security and safety, are they aware that they’re afraid of being sexually assaulted? Violence against women is, on a global scale, so common that some experts consider it a "normal” aspect of women’s experiences—and yet research on the issue is subjective and inconsistent.

Women and Violence is a comprehensive look at the issue of violence against women and its many appearances, causes, costs and consequences. Understanding that personal values, beliefs and environment affect an individual’s response to—and acknowledgement of—violence against women, this book addresses topics such as global perspectives on violence, controversies and debates, and social change strategies and activism.

Series:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use