By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

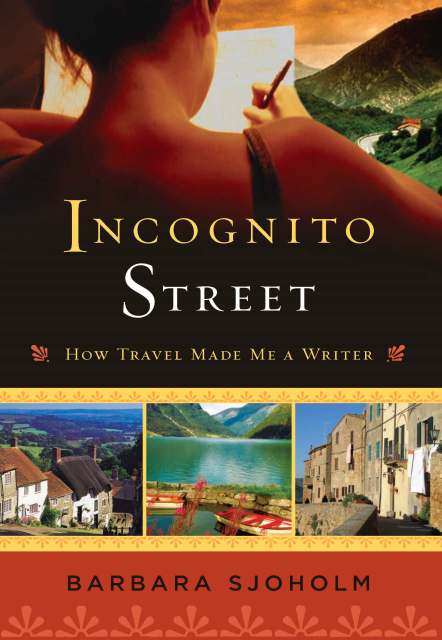

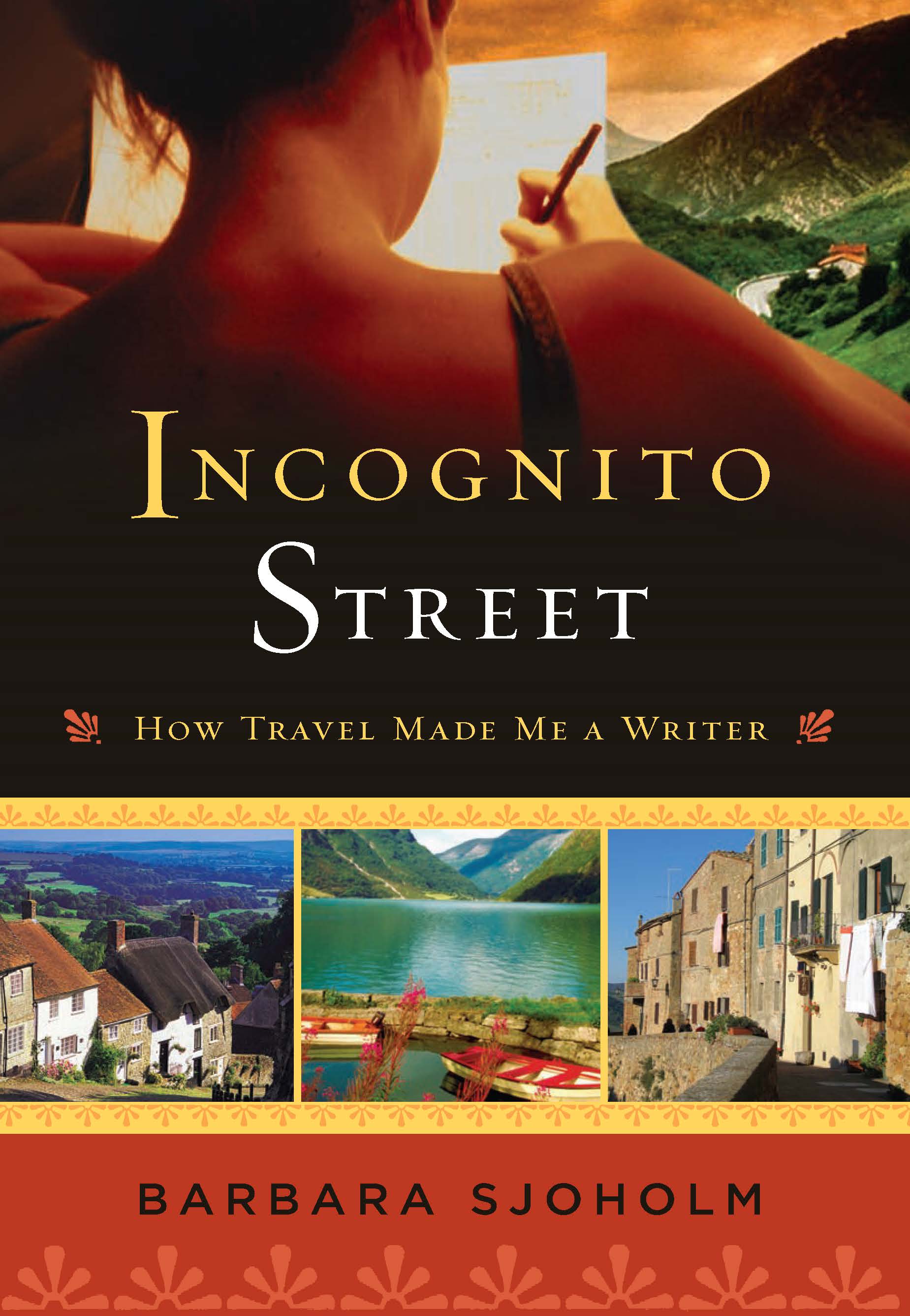

Incognito Street

How Travel Made Me a Writer

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 7, 2015

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580056069

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 7, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Barbara Sjoholm arrived in London in the winter of 1970 at the age of twenty. Like countless young Americans in that tumultuous time, she wanted to leave a country at war and explore Europe; a small inheritance from her grandmother gave her the opportunity.

Over the next three years, she lived in Barcelona, hitchhiked around Spain, and studied at the University of Granada. She managed a sourvenir shop in the Norwegian mountains and worked as a dishwasher on the Norwegian Coastal Steamer. Set on becoming a writer, she read everything from Colette to Dickens to Borges, changing her style and her subject every few weeks, and gradually found her voice. Incognito Street is the story of a young woman's search for artistic, political, and sexual identity while digesting the changing world around her.

As she sheds the ghosts of her childhood, we come to know her quiet yet adventurous spirit. In moments that are tender, funny, bewildering, and suspenseful, we see an evocative look at Europe through the blossoming writer’s maturing eyes.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use