By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

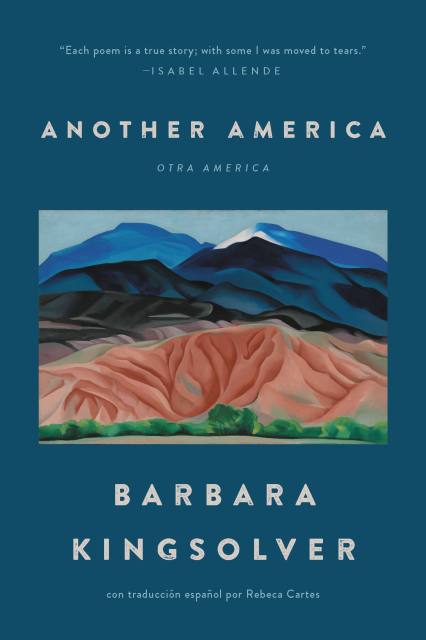

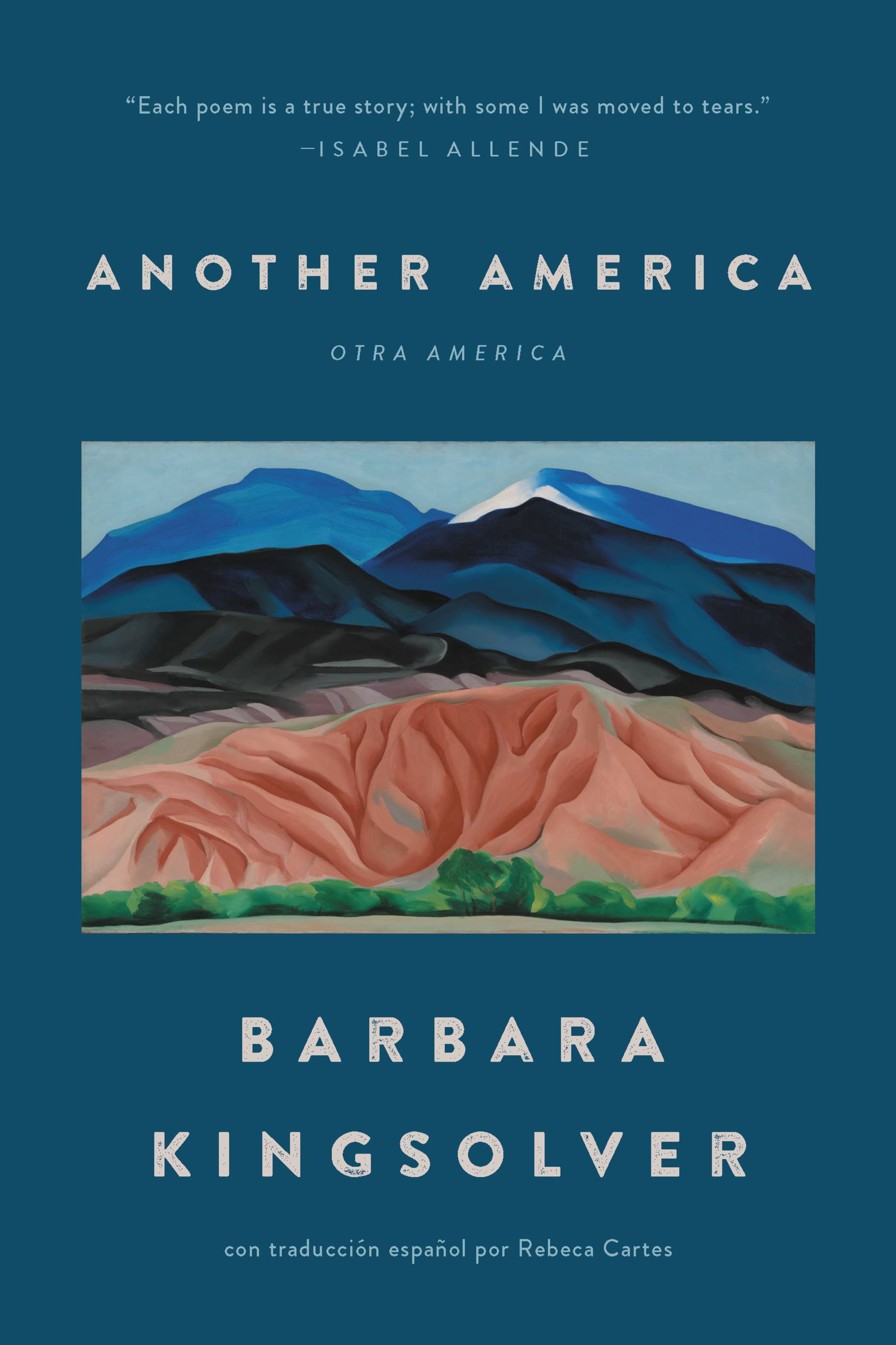

Another America/Otra America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 22, 2022

- Page Count

- 144 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781541600386

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 22, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From a bestselling and beloved author, an intensely personal collection of poetry “rich with political and human resonance” (Ursula K. LeGuin)

Before becoming the bestselling author we know today, Barbara Kingsolver, as a new college graduate in search of adventure, moved to the borderlands of Tucson, Arizona. What she found, she says, was “another America.”

Interweaving past political events, from the US-backed dictatorships in South America to the government surveillance carried out in the Reagan years, Kingsolver’s early poetry expands into a broader examination of the racism, discrimination, and immigration system she witnessed at close range. The poems coalesce in a record of her emerging adulthood, in which she confronts the hypocrisy of the national myth of America—a confrontation that would come to shape her not only as an artist, but as a citizen. With a new introduction from Kingsolver that reflects on the current border crisis, Another America is a striking portrait of a country deeply divided between those with privilege and those without, and the lives of urgent purpose that may be carved out in between.

Genre:

-

“Barbara Kingsolver belongs in the company of such poets as Clifton, Levertov, Hogan, Forché and Rich. Her pure American voice, chorded in both the great American languages, is rich with political and human resonance.”Ursula K. LeGuin

-

“Each poem is a true story; with some I was moved to tears.”Isabelle Allende

-

“These poems made me stop mid-book, telephone a friend and brave saying the unsayable – palabras del corazón that often go unsaid.”Sanda Cisneros

-

“The best of American political poetry, melding emotion and analysis, daily life and national issues, voice and heart.”Booklist

-

“This powerful collection of poetry deals with protest against political and social repression experienced by ordinary people, particularly women, under military regimes in Central and South America during the last 20 years. Through vivid imagery and compelling messages, Kingsolver makes a passionate appeal to end the suffering of victims of revolution, oppression, and war.”School Library Journal

-

“[Kingsolver’s] poems present a vision of an underprivileged America redressed, and are, in that respect, songs of hope and longing as opposed to howls of protest and despair.”Foreword Magazine

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use