Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

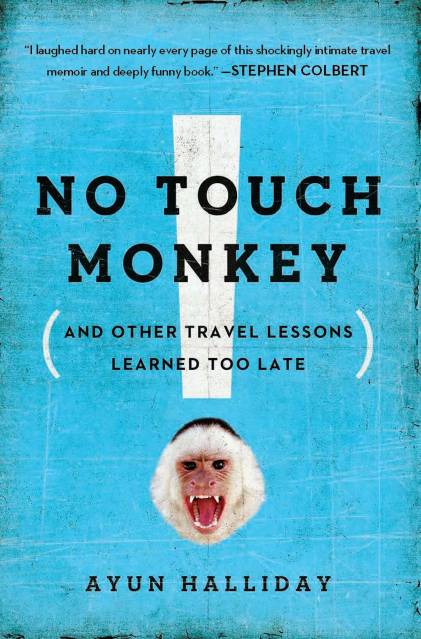

No Touch Monkey!

And Other Travel Lessons Learned Too Late

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 25, 2015

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580056021

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $17.00 $21.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 25, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Ayun Halliday may not make for the most sensible travel companion, but she is certainly one of the zaniest, with a knack for inserting herself (and her unwitting cohorts) into bizarre situations around the globe. Curator of kitsch and unabashed aficionada of pop culture, Halliday offers bemused, self-deprecating narration of events from guerrilla theater in Romania to drug-induced Apocalypse Now reenactments in Vietnam to a perhaps more surreal collagen-implant demonstration at a Paris fashion show emceed by Lauren Bacall. On layover in Amsterdam, Halliday finds unlikely trouble in the red-light district — eliciting the ire of a tiny, violent madam, and is forced to explain tampons to soldiers in Kashmir — “they’re for ladies. Bleeding ladies” — that, she admits, “might have looked like white cotton bullets lined up in their box.”

A self-admittedly bumbling vacationer, Halliday shares — with razor-sharp wit and to hilarious effect — the travel stories most are too self-conscious to tell.

Includes line drawings, generously provided by the author.