By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

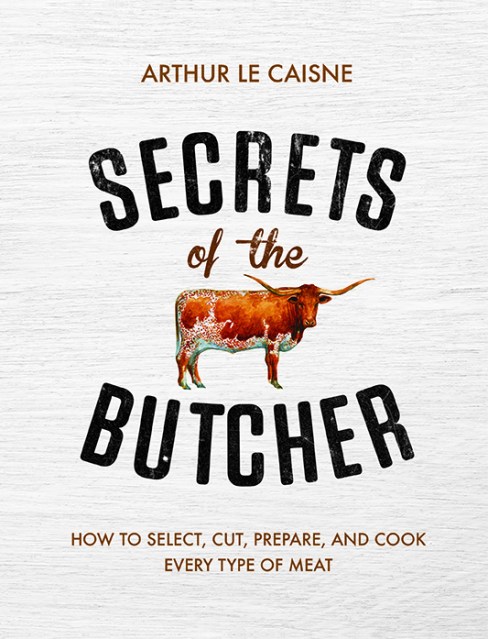

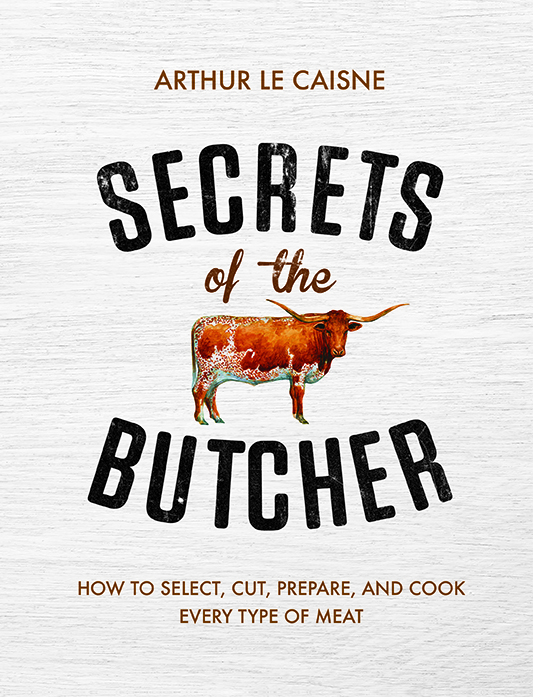

Secrets of the Butcher

How to Select, Cut, Prepare, and Cook Every Type of Meat

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 1, 2018

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780316480666

Price

$27.99Price

$33.99 CADFormat

Format:

Hardcover $27.99 $33.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 1, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In Secrets of the Butcher, author Arthur Le Caisne takes readers step-by-step through the ever-evolving and artisanal world of meat. Organized by type of protein — beef, veal, pork, lamb, poultry, and turkey — the book categorizes and describes the origin and characteristics of the best of each type. Secrets of the Butcher also includes state-of-the-art information on techniques and little know tricks of the trade, including answers to variety of questions such as What is dry aging? Is a sharp knife the best to cut meat? Is it better to pre-salt meat several days in advance or just before or after cooking and why? Do marinades really works? At what temperature is it best to cook meat? Is resting the meat after cooking really necessary? And much more. Accurate, scientific, and fully illustrated throughout with clear and useful four-color illustrations, Secrets of the Butcher is a must have for anyone serious about cooking meat.

Genre:

-

"Anyone who loves to cook or eat meat deserves a copy of this hardcover. On page after inviting page, Arthur Le Caisne details everything you need to know (and much that you didn't know you needed to know but will be glad to) about beef, pork, lamb, poultry, and game."Fine Cooking

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use