By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

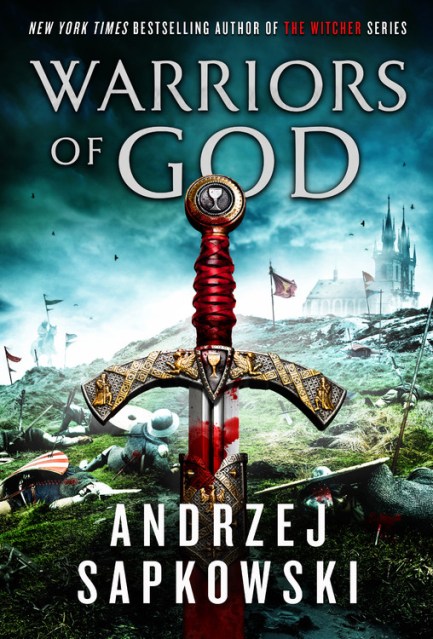

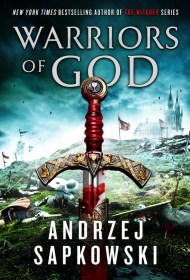

Warriors of God

Contributors

Translated by David French

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 19, 2021

- Page Count

- 656 pages

- Publisher

- Orbit

- ISBN-13

- 9780316593243

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $44.99

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 19, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From the New York Times bestselling author of The Witcher: Reynevan—scoundrel, magician, possibly a fool—travels into the depths of war as he attempts to navigate the religious fervors of the fifteenth century.

When the Hussite leaders entrust Reynevan with a dangerous secret mission, he is forced to come out of hiding in Bohemia and depart for Silesia. At the same time, he strives to avenge the death of his brother and discover the whereabouts of his beloved. Once again pursued by multiple enemies, he must contend with danger on every front.

Full of gripping action replete with twists and mysteries, seasoned with magic and Sapkowski’s ever-present wit, fans of the Witcher will appreciate this rich historical epic set during the Hussite Wars.

Praise for the The Tower of Fools, book one of the Hussite Trilogy:

“This is historical fantasy done right.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“A fantastic novel that any fan of The Witcher will instantly appreciate.” —The Gamer

“A ripping yarn delivered with world-weary wit, bursting at the seams with sex, death, magic and madness.” —Joe Abercrombie

“Sapkowski’s energetic and satirical prose as well as the unconventional setting makes this a highly enjoyable historical fantasy.” —Booklist

Also by Andrzej Sapkowski:

The Hussite Trilogy

The Tower of Fools

Warriors of God

Witcher collections

The Last Wish

Sword of Destiny

Witcher novels

Blood of Elves

The Time of Contempt

Baptism of Fire

The Tower of Swallows

Lady of the Lake

Season of Storms

The Malady and Other Stories: An Andrzej Sapkowski Sampler (e-only)

Translated by David French

When the Hussite leaders entrust Reynevan with a dangerous secret mission, he is forced to come out of hiding in Bohemia and depart for Silesia. At the same time, he strives to avenge the death of his brother and discover the whereabouts of his beloved. Once again pursued by multiple enemies, he must contend with danger on every front.

Full of gripping action replete with twists and mysteries, seasoned with magic and Sapkowski’s ever-present wit, fans of the Witcher will appreciate this rich historical epic set during the Hussite Wars.

Praise for the The Tower of Fools, book one of the Hussite Trilogy:

“This is historical fantasy done right.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“A fantastic novel that any fan of The Witcher will instantly appreciate.” —The Gamer

“A ripping yarn delivered with world-weary wit, bursting at the seams with sex, death, magic and madness.” —Joe Abercrombie

“Sapkowski’s energetic and satirical prose as well as the unconventional setting makes this a highly enjoyable historical fantasy.” —Booklist

Also by Andrzej Sapkowski:

The Hussite Trilogy

The Tower of Fools

Warriors of God

Witcher collections

The Last Wish

Sword of Destiny

Witcher novels

Blood of Elves

The Time of Contempt

Baptism of Fire

The Tower of Swallows

Lady of the Lake

Season of Storms

The Malady and Other Stories: An Andrzej Sapkowski Sampler (e-only)

Translated by David French

Genre:

Series:

-

"Sapkowski's love for the period is clear as he touches on notorious historical events and figures ... The carefully painted landscapes and intricate politics effortlessly draw readers into Reinmar's life and times. This is historical fantasy done right."Publishers Weekly (starred review) on Tower of Fools

-

"A ripping yarn delivered with world-weary wit, bursting at the seams with sex, death, magic and madness."Joe Abercrombie on Tower of Fools

-

"Sapkowski's energetic and satirical prose as well as the unconventional setting makes this a highly enjoyable historical fantasy. Recommended for Sapkowksi's many existing fans."Booklist on Tower of Fools

-

"[The Tower of Fools] is a fantastic novel that any fan of The Witcher will instantly appreciate . . . Reynevan is an intelligent dope who follows his heart, his accompanying cast of characters is thoroughly developed and just as intriguing, and the worldbuilding employed by Sapkowski is impeccable."The Gamer on Tower of Fools

-

“Sapkowski’s primary draw is his ability to weave rich historical context with a complex atmosphere of magic and superstition . . . [The Tower of Fools] is quite rewarding for readers ready to take the plunge.”BookPage on Tower of Fools

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use