Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

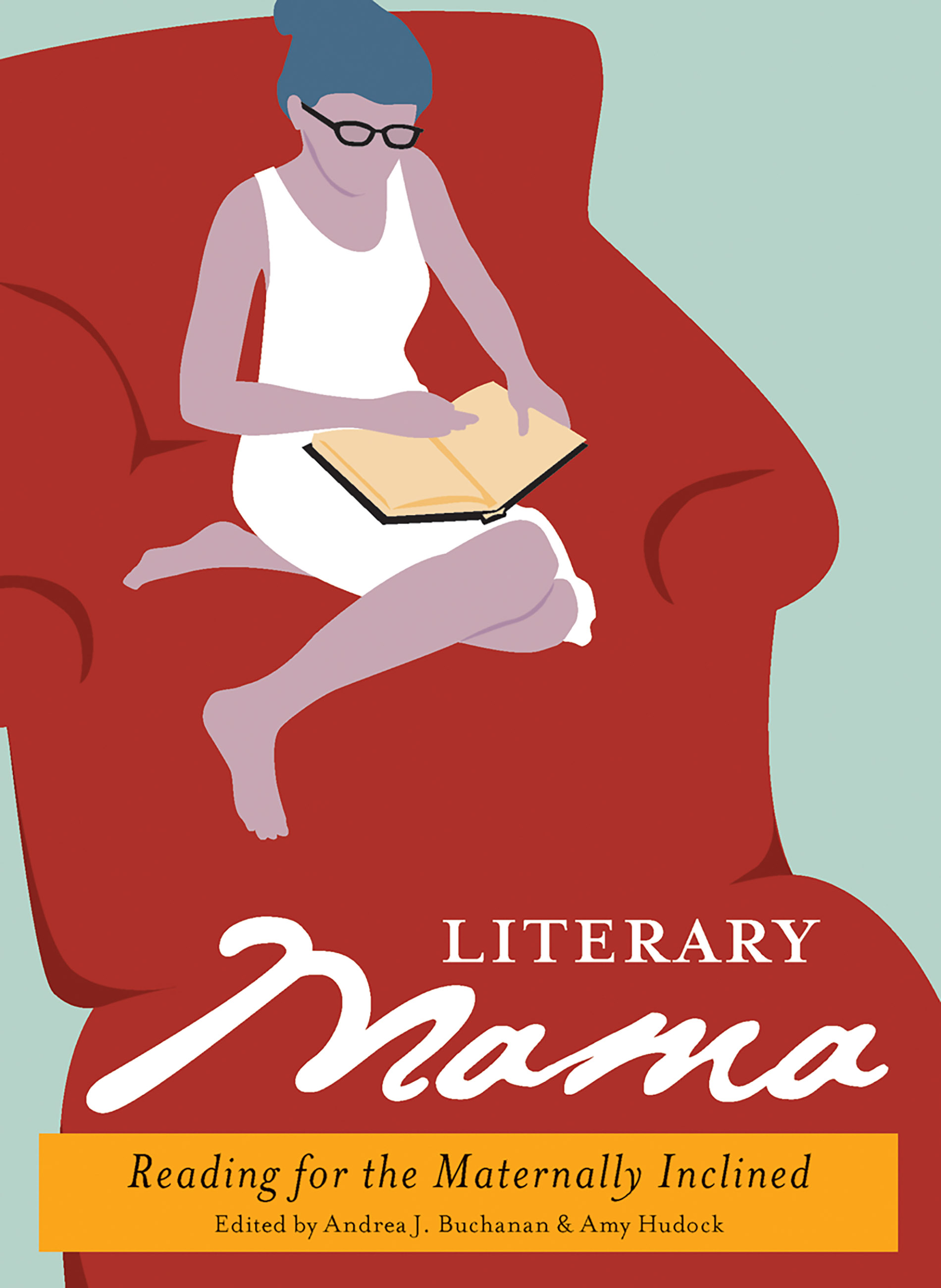

Literary Mama

Reading for the Maternally Inclined

Contributors

Edited by Andrea J. Buchanan

Edited by Amy Hudock

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 10, 2009

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580053358

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 10, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Becoming a mother takes more than the physical act of giving birth or completing an adoption: it takes birthing oneself as a mother through psychological, intellectual, and spiritual work that continues throughout life. Yet most women’s stories of personal growth after motherhood tend to remain untold. As writers and mothers, Andrea Buchanan and Amy Hudock were frustrated by what they perceived as a lack of writing by mothers that captured the ambiguity, complexity, and humor of their experiences. So they decided to create the place they wanted to find, with the kind of writing they wanted to read.

This unique collection features the best of the online magazine literarymama.com, a site devoted to mama-centric writing with fresh voices, superior craft, and vivid imagery. While the majority of literature on parenting is not literary or is not written by mothers, this book is both. Including creative nonfiction, fiction, and poetry, Literary Mama celebrates the voices of the maternally inclined, paves the way for other writer mamas, and honors the difficult and rewarding work women do as they move into motherhood.

This unique collection features the best of the online magazine literarymama.com, a site devoted to mama-centric writing with fresh voices, superior craft, and vivid imagery. While the majority of literature on parenting is not literary or is not written by mothers, this book is both. Including creative nonfiction, fiction, and poetry, Literary Mama celebrates the voices of the maternally inclined, paves the way for other writer mamas, and honors the difficult and rewarding work women do as they move into motherhood.