Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

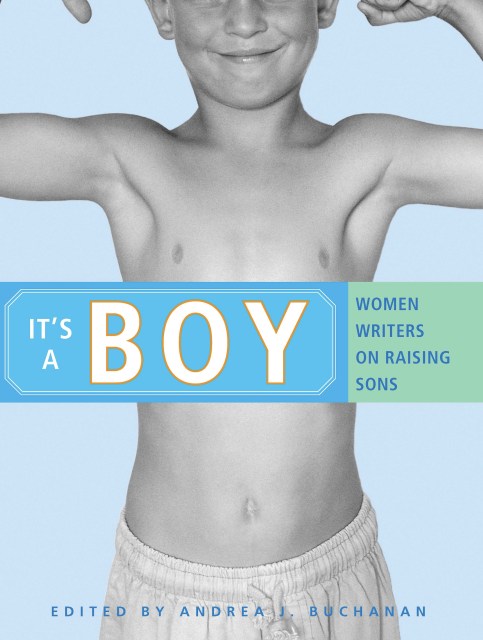

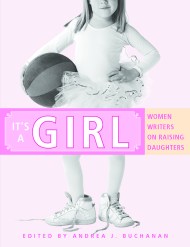

It’s a Boy

Women Writers on Raising Sons

Contributors

Edited by Andrea J. Buchanan

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 13, 2009

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786746323

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 13, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The most popular question any pregnant woman is asked, aside from "When are you due?", has got to be "Are you having a girl or a boy?"

When author Andrea Buchanan, already a mom to a little girl, was pregnant with her second child, she marveled at the response of friends and total strangers alike: "Boys are wonderful," "Boys are so much better than girls," "Boys love their mothers differently than girls."

This constant refrain led her to explore the issue herself, with help from her fellow writers and moms, many of whom had had the same experience. The result is It's A Boy, a wide-ranging, often-humorous, and honest collection of essays about the experience of mothering boys. Taking on topics like aggression, parenting a teenage boy, and wishing for a daughter but getting a son, It's A Boy explores what it's like to mother sons and how that experience may be different, but no less satisfying, than mothering girls.