By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

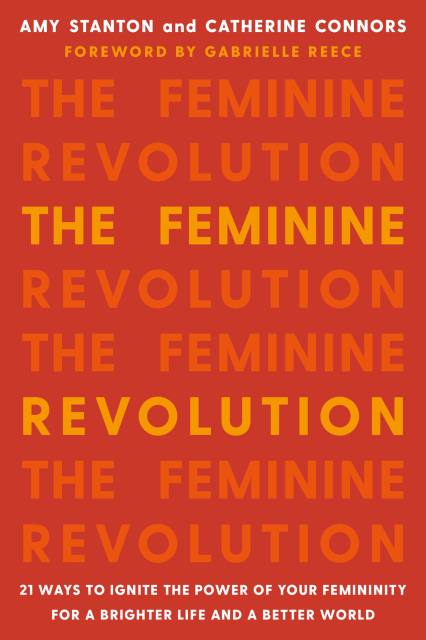

The Feminine Revolution

21 Ways to Ignite the Power of Your Femininity for a Brighter Life and a Better World

Contributors

By Amy Stanton

Foreword by Gabby Reece

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 6, 2018

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580058131

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 6, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Challenging old and outdated perceptions that feminine traits are weaknesses, The Feminine Revolution revisits those characteristics to show how they are powerful assets that should be embraced rather than maligned. It argues that feminine traits have been mischaracterized as weak, fragile, diminutive, and embittered for too long, and offers a call to arms to redeem them as the superpowers and gifts that they are.

The authors, Amy Stanton and Catherine Connors, begin with a brief history of when-and-why these traits were defined as weaknesses, sharing opinions from iconic females including Marianne Williamson and Cindy Crawford. Then they offer a set of feminine principles that challenge current perceptions of feminine traits, while providing women new mindsets to reclaim those traits with confidence. The principles include counterintuitive messages, including:

Take things hard. Women feel things deeply, especially the hard stuff — and that’s a good thing.

Enjoy glamour. Peacocks’ bright coloring and garish feathers are part of their survival strategy — similar tactics are part of our happiness strategy.

Chit-chat. Women have been derogated for “gossip” for centuries. But what others call gossip, we call social connection.

Emote. Never let anyone tell you to not be emotional. Express your enthusiasm, love, affection and warmth.

Embrace your domestic side. Don’t be ashamed to cultivate the beauty of your home and wrap your arms around friends and family.

With an upbeat blend of self-help and fresh analysis, The Feminine Revolution reboots femininity for the modern woman and provides her with the tools to accept and embrace her own authentic nature.

-

"Nothing could be a more critical conversation than the one women are engaged in now, trying to connect our femininity with our power in a way that delivers us to our highest selves. Kudos to Amy Stanton and Catherine Connors for exploring issues--often hidden, sometimes painful--that pave the way to genuine deliverance from the forces that hold us back."

--Marianne Williamson

-

"I'd love for my daughter to grow up in a world where then men and women in her life support her and in which she won't have to sacrifice her femininity for the expense of her success. The Feminine Revolution is a beautiful exploration of that idea and can help lay the groundwork for that future."--Justin Baldoni, actor, filmmaker, and public speaker

-

"This new book recasts female attributes in an empowering light."Cosmopolitan

-

"The Feminine Revolution [shows us how to] reclaim the true power of "feminine" traits like emotional attunement and social connection."People Magazine

-

"Honest, bold, incendiary."goop.com

-

"Authors Amy Stanton and Catherine Connors share the history behind why values linked to femininity may have been considered "weak," and illustrate why these traits today can be your leadership superpowers."forbes.com

-

"Radically subversive-and illuminating."Ms. Magazine

-

"The Feminine Revolution is the antidote to the current autoimmune epidemic and the Rx for the new feminine consciousness, health, and healing."--Dr. Habib Sadeghi, physician and author of The Clarity Cleanse

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use