Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

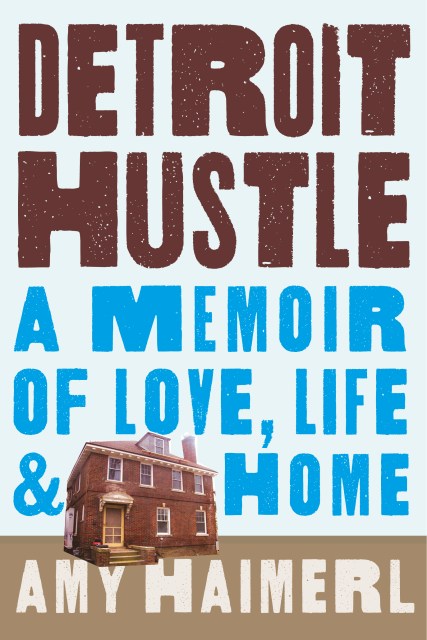

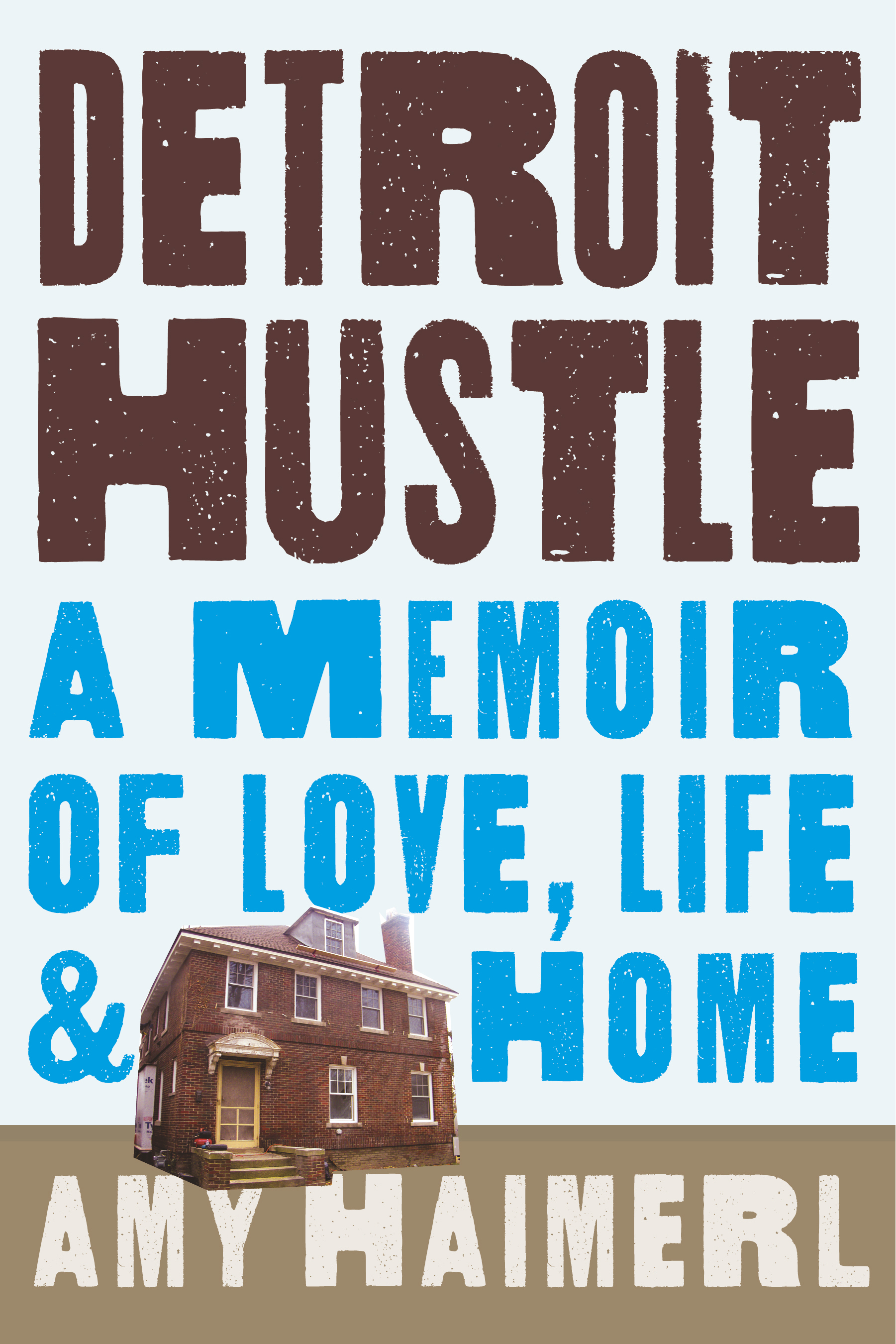

Detroit Hustle

A Memoir of Life, Love, and Home

Contributors

By Amy Haimerl

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $24.00 $30.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 3, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

As she and her husband restore the 1914 Georgian Revival, a stately brick house with no plumbing, no heat, and no electricity, Amy finds a community of Detroiters who, like herself, aren’t afraid of a little hard work or things that are a little rough around the edges. Filled with amusing and touching anecdotes about navigating a real-estate market that is rife with scams, finding a contractor who is a lover of C.S. Lewis and willing to quote him liberally, and neighbors who either get teary-eyed at the sight of newcomers or urge Amy and her husband to get out while they can, Amy writes evocatively about the charms and challenges of finding her footing in a city whose future is in question. Detroit Hustle is a memoir that is both a meditation on what it takes to make a house a home, and a love letter to a much-derided city.

Genre:

-

“A love song sung to a house and a city, but it's also a money memoir, one marked by ignorance at the outset and a triumph of feelings over financial facts.”

–The New York Times

This memoir of home renovation in Detroit delves into much more, including the importance of place, the meaning of urban revival and the building of lives and loves.

–Shelf awareness

"An engaging and cautiously optimistic memoir of making a new life."

–Kirkus Reviews

“With humor and incisiveness, Haimerl shares the journey of turning a house into a home …. As a financial journalist, she adeptly reports on the city's financial situation and its newest entrepreneurial efforts…This book is about more than the blight of Detroit; it is also about making a new home and community in a rapidly changing city.”

–Publishers Weekly

“Surprisingly full of practical advice and always entertaining.”

–Library Journal -

"The amazing charm of Detroit Hustle by Amy Haimerl is its brilliant use of concurrent narratives - one quite personal, one about a down-on-its-luck city trying to get up off its knees - to show how perseverance, community and love are so essential to both stories. Each chapter has you rooting for the city, but also cheering for the writer and her husband, their neighbors and family, and the expansive house renovation project whose journey, hiccups and all, makes them into Detroiters."

–Stephen Henderson, Pulitzer Prize-winning Detroit Free Press editorial page editor

"Detroit Hustle is much more than a book about restoring a house. It's about a city and its people abandoned to the churn of change, about fitting in and standing out, about decades of decay and wispy hopes of revival. It's America's story. Amy Haimerl's memoir is as gritty and gripping as Detroit itself."

–Ron Fournier, columnist, The Atlantic, and author of Love That Boy: What Two Presidents, Eight Road Trips, and My Son Taught Me About a Parent's Expectations

- On Sale

- May 3, 2016

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762457441

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use