By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

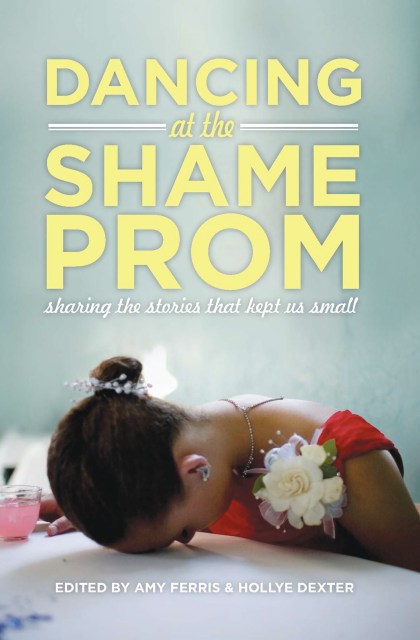

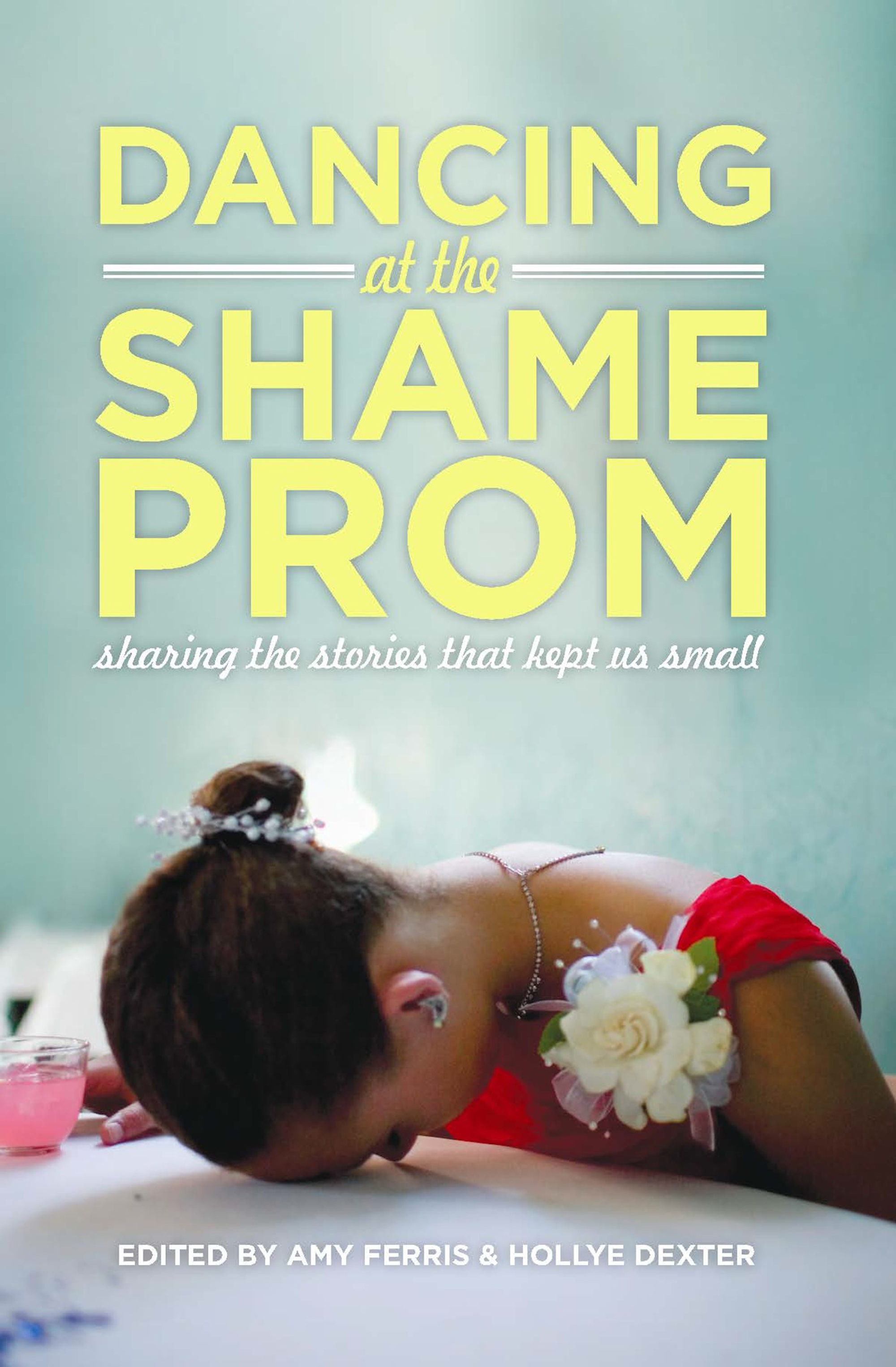

Dancing at the Shame Prom

Sharing the Stories That Kept Us Small

Contributors

Edited by Amy Ferris

Edited by Hollye Dexter

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 2, 2012

- Page Count

- 264 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580054669

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 2, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Shame is a powerful thing. It can weigh on your heart and mind, diminish your sense of self-worth, and impact the way you live in the world. But what happens when you share that secret burden?

Amy Ferris, Hollye Dexter, and the writers they brought together are all ready to let go of shame. In Dancing at the Shame Prom, twenty-six extraordinary women-Lyena Strelkoff, Teresa Stack, Monica Holloway, Nina Burleigh, Amy Friedman, Meredith Resnick, Victoria Zackheim, and more—take the plunge and say "yes” to sharing their stories. These brave writers, journalists, musicians, artists, directors, and activists have offered up their most funny, sad, poignant, miraculous, life-changing, and jaw-dropping secrets for you to gawk at, empathize with, and learn from—in the hopes that they will inspire others to do the same. Letting go feels good!

Freeing, provocative, and audacious, Dancing at the Shame Prom is about flaunting the secrets that have made you feel small so that you can stand up straight, let the shame go, and finally—decisively—move on with your life.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use