By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

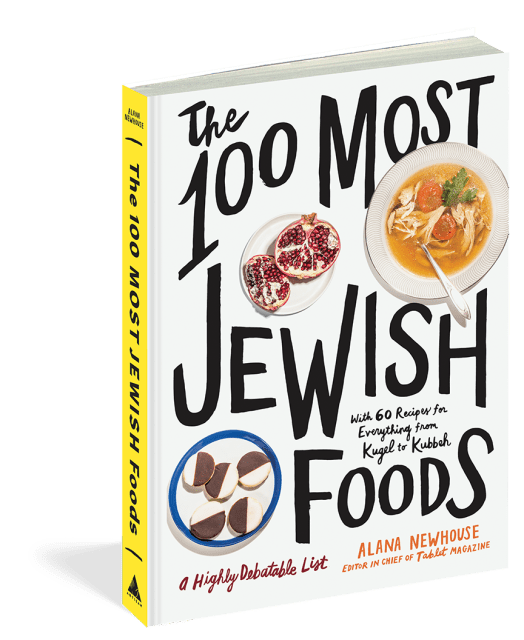

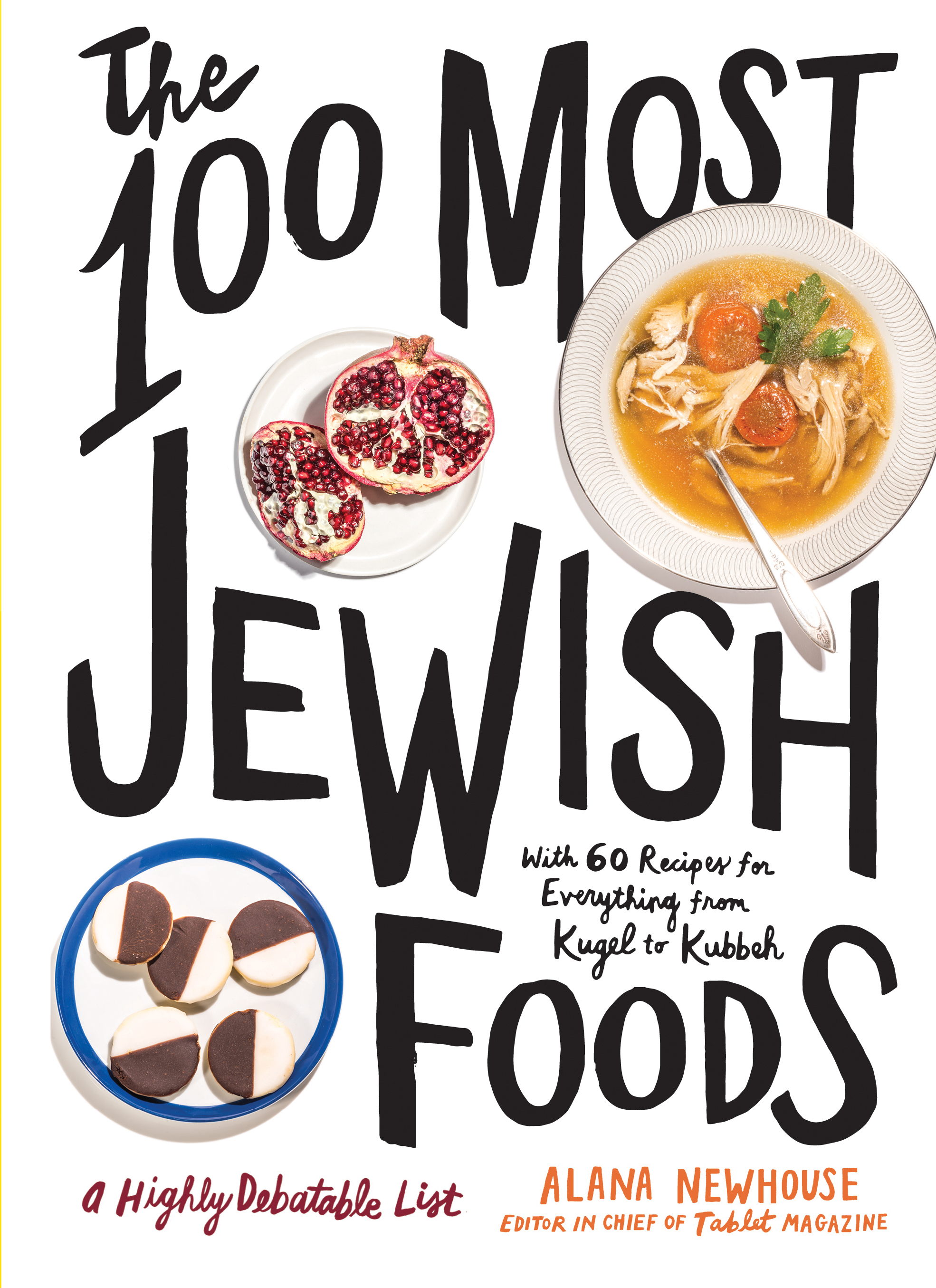

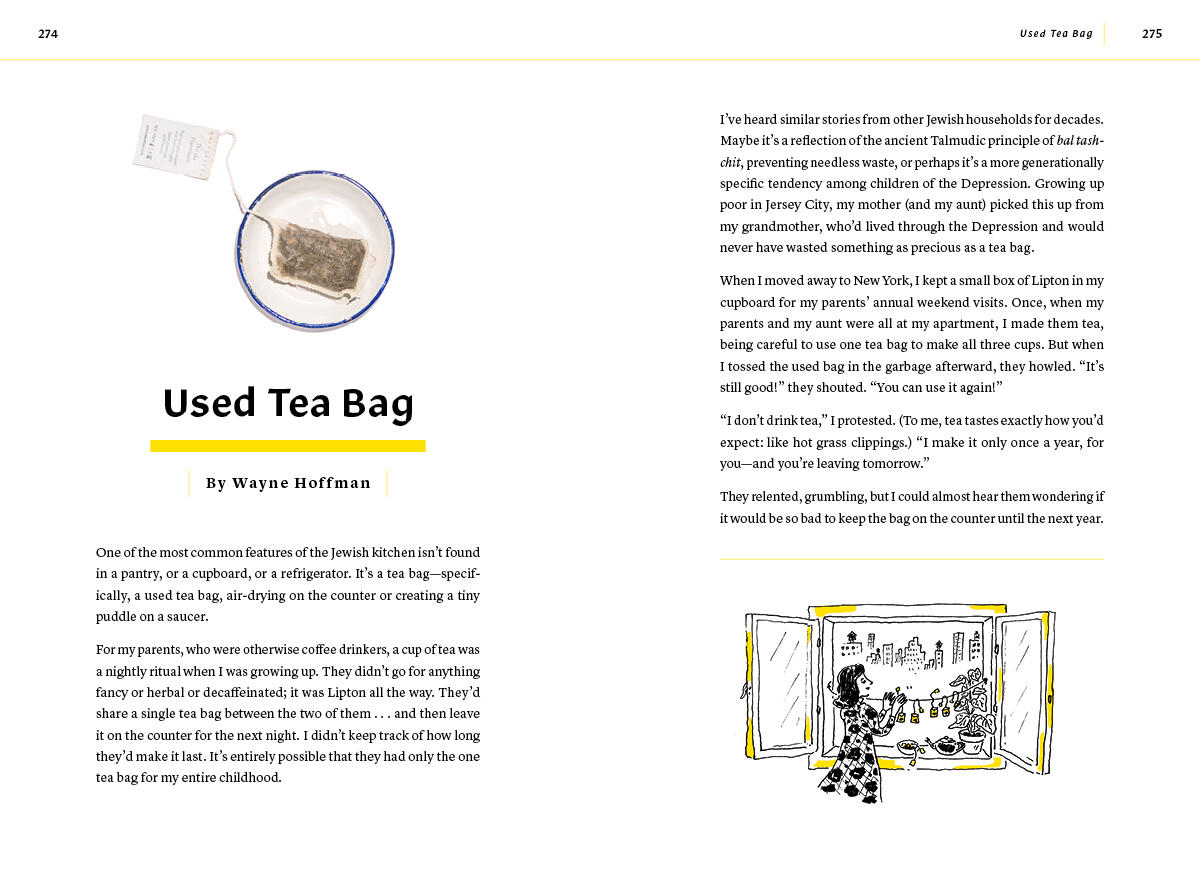

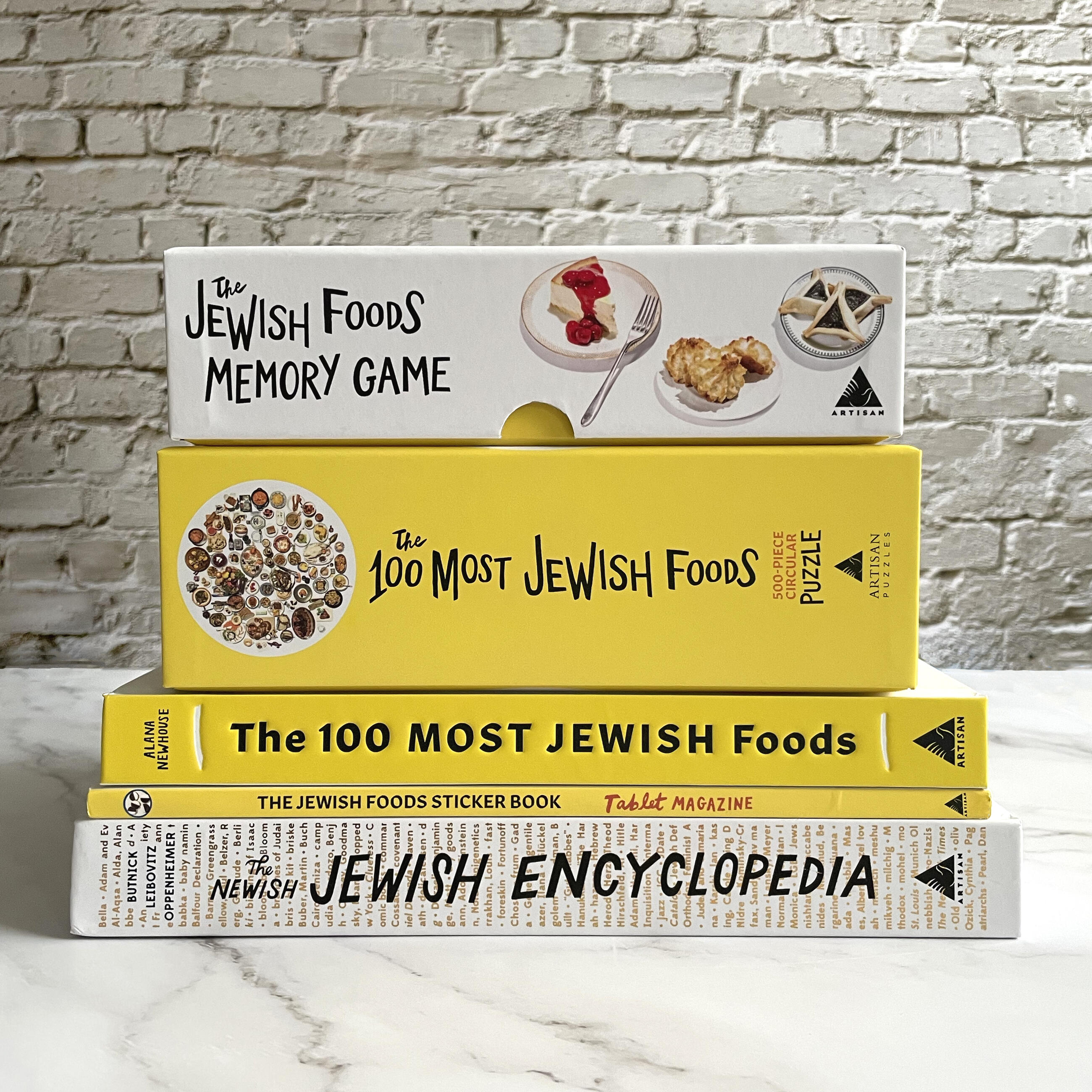

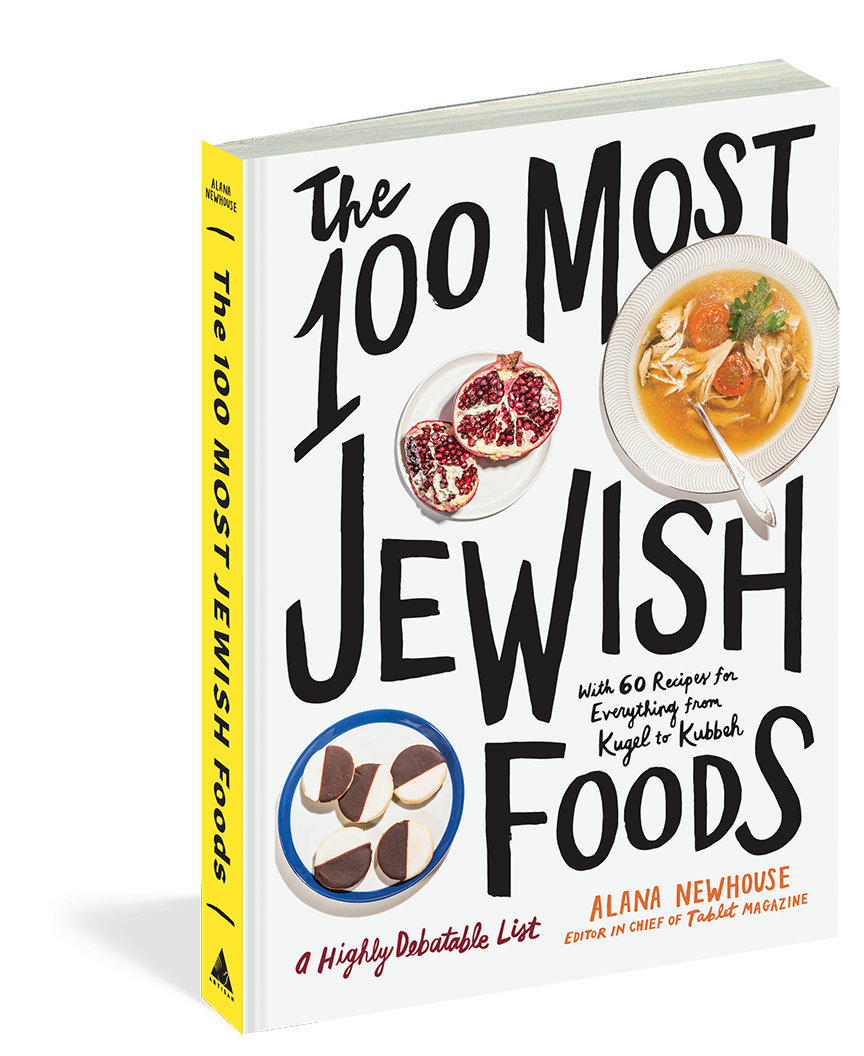

The 100 Most Jewish Foods

A Highly Debatable List

Contributors

By Tablet

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 19, 2019

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Artisan

- ISBN-13

- 9781579659066

Price

$24.95Price

$30.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $24.95 $30.95 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 19, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“Your gift giving problems are now over—just stock up on The 100 Most Jewish Foods. . . . The appropriate gift for any occasion.”

—Jewish Book Council

“[A] love letter—to food, family, faith and identity, and the deliciously tangled way they come together.”

—NPR’s The Salt

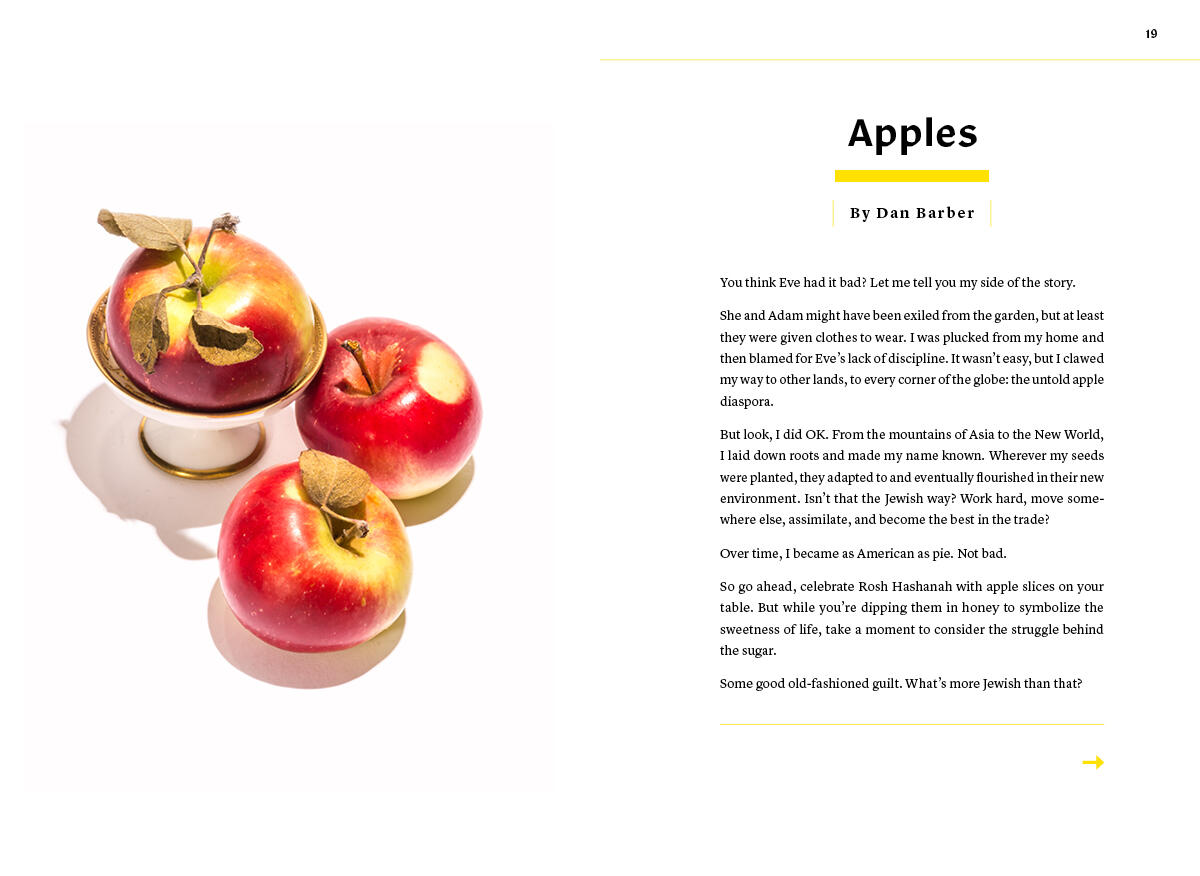

With contributions from Ruth Reichl, Éric Ripert, Joan Nathan, Michael Solomonov, Dan Barber, Yotam Ottolenghi, Tom Colicchio, Maira Kalman, Melissa Clark, and many more!

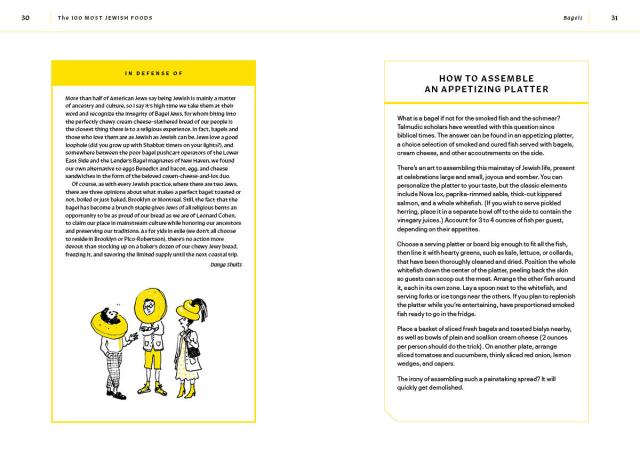

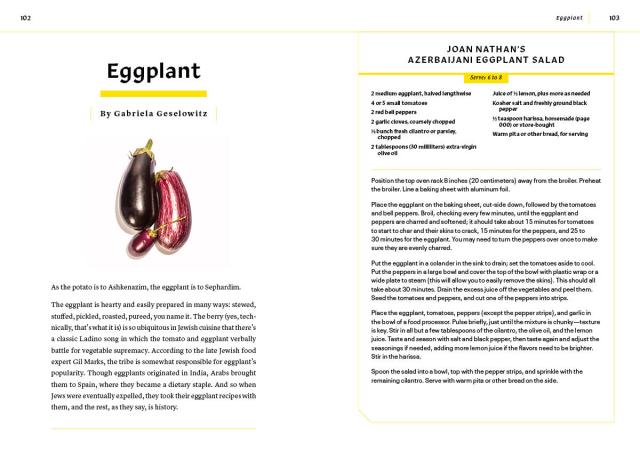

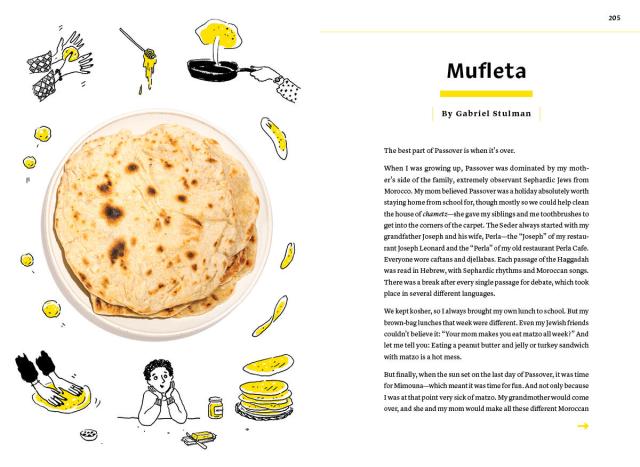

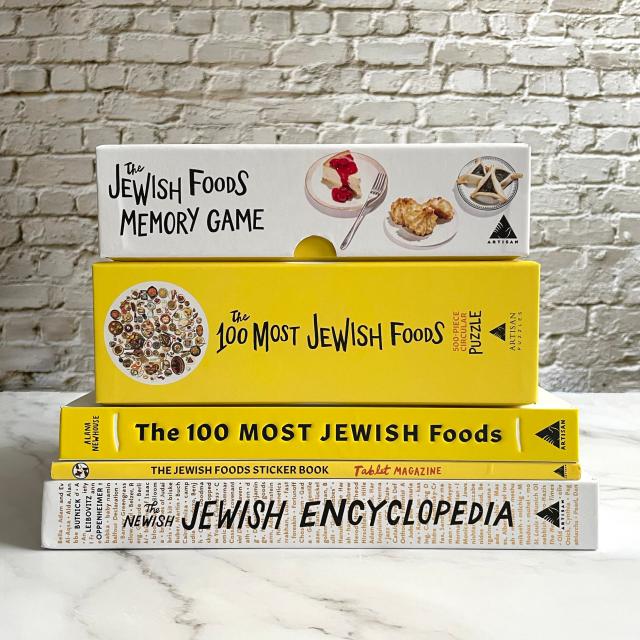

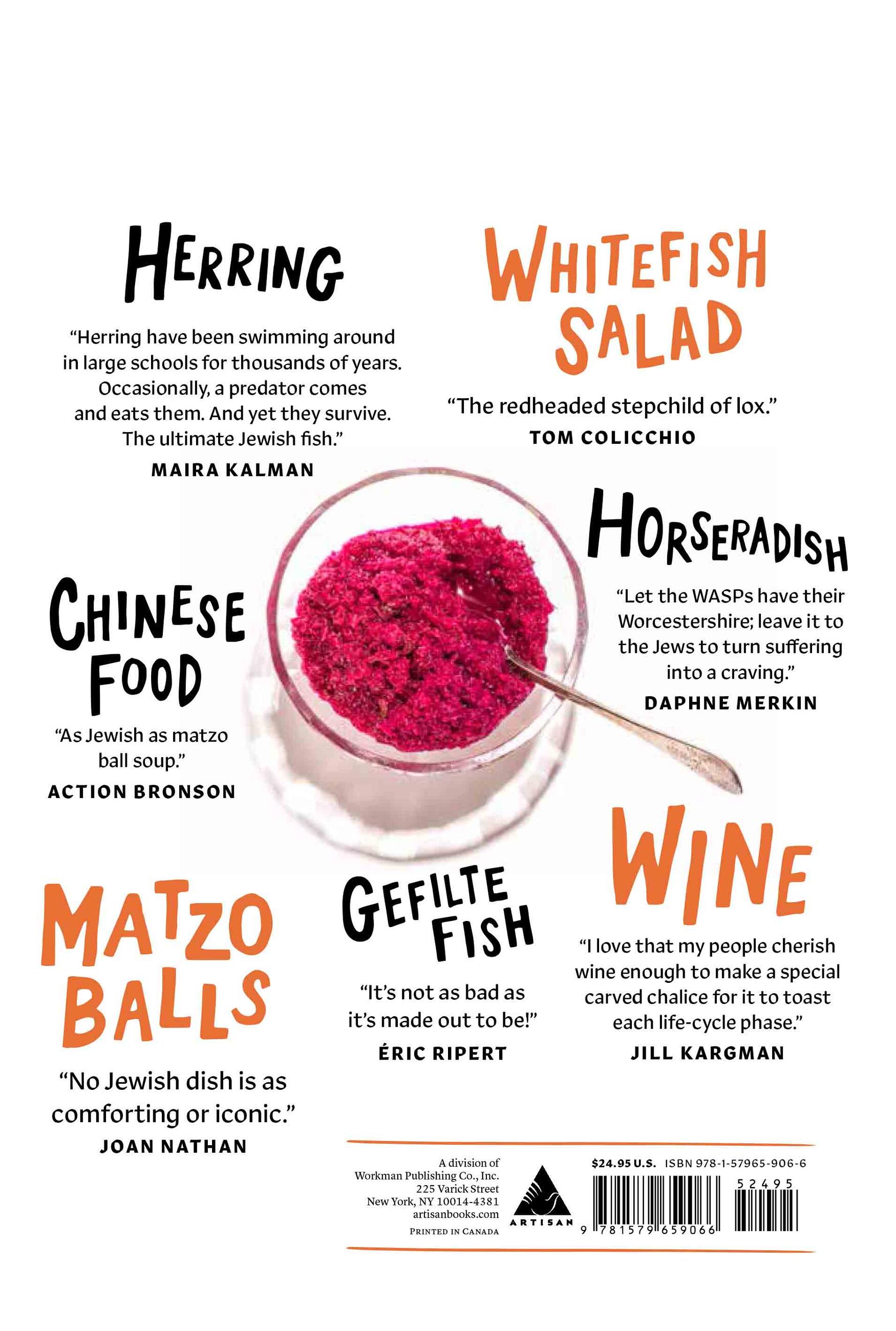

Tablet’s list of the 100 most Jewish foods is not about the most popular Jewish foods, or the tastiest, or even the most enduring. It’s a list of the most significant foods culturally and historically to the Jewish people, explored deeply with essays, recipes, stories, and context. Some of the dishes are no longer cooked at home, and some are not even dishes in the traditional sense (store-bought cereal and Stella D’oro cookies, for example). The entire list is up for debate, which is what makes this book so much fun. Many of the foods are delicious (such as babka and shakshuka). Others make us wonder how they’ve survived as long as they have (such as unhatched chicken eggs and jellied calves’ feet). As expected, many Jewish (and now universal) favorites like matzo balls, pickles, cheesecake, blintzes, and chopped liver make the list. The recipes are global and represent all contingencies of the Jewish experience. Contributors include Ruth Reichl, Éric Ripert, Joan Nathan, Michael Solomonov, Dan Barber, Gail Simmons, Yotam Ottolenghi, Tom Colicchio, Amanda Hesser and Merrill Stubbs, Maira Kalman, Action Bronson, Daphne Merkin, Shalom Auslander, Dr. Ruth Westheimer, and Phil Rosenthal, among many others. Presented in a gifty package, The 100 Most Jewish Foods is the perfect book to dip into, quote from, cook from, and launch a spirited debate.

—Jewish Book Council

“[A] love letter—to food, family, faith and identity, and the deliciously tangled way they come together.”

—NPR’s The Salt

With contributions from Ruth Reichl, Éric Ripert, Joan Nathan, Michael Solomonov, Dan Barber, Yotam Ottolenghi, Tom Colicchio, Maira Kalman, Melissa Clark, and many more!

Tablet’s list of the 100 most Jewish foods is not about the most popular Jewish foods, or the tastiest, or even the most enduring. It’s a list of the most significant foods culturally and historically to the Jewish people, explored deeply with essays, recipes, stories, and context. Some of the dishes are no longer cooked at home, and some are not even dishes in the traditional sense (store-bought cereal and Stella D’oro cookies, for example). The entire list is up for debate, which is what makes this book so much fun. Many of the foods are delicious (such as babka and shakshuka). Others make us wonder how they’ve survived as long as they have (such as unhatched chicken eggs and jellied calves’ feet). As expected, many Jewish (and now universal) favorites like matzo balls, pickles, cheesecake, blintzes, and chopped liver make the list. The recipes are global and represent all contingencies of the Jewish experience. Contributors include Ruth Reichl, Éric Ripert, Joan Nathan, Michael Solomonov, Dan Barber, Gail Simmons, Yotam Ottolenghi, Tom Colicchio, Amanda Hesser and Merrill Stubbs, Maira Kalman, Action Bronson, Daphne Merkin, Shalom Auslander, Dr. Ruth Westheimer, and Phil Rosenthal, among many others. Presented in a gifty package, The 100 Most Jewish Foods is the perfect book to dip into, quote from, cook from, and launch a spirited debate.

-

“Amusing, yet serious.”Publishers Weekly

B>New York Times

“[A] love letter—to food, family, faith and identity, and the deliciously tangled way they come together.”

B>NPR’s The Salt

“Your gift giving problems are now over — just stock up on The 100 Most Jewish Foods: A Highly Debatable List. This book will help deal with one of life’s most persistent problems, the appropriate gift for any occasion — hostess present, Hanukkah, engagement, birthday, or get well.”

B>Jewish Book Council

“Wholly original. . . . The whimsical, hilarious, nostalgic and, at times, serious collection reminds me of a boisterous dinner party with all your favorite foodies and chefs coming together against the backdrop of a laid-back panel on their experiences with Jewish food. . . . A real treat.”

B>Hadassah

“A perfect gift for this Passover—gorgeous and funny and well written. . . . The 100 Most Jewish Foods is also unafraid of the ways in which food can be a window into history, culture, and politics.”

B>Bklyner

“An entertaining choice for anyone interested in how food reflects a people and helps connect them to shared traditions.”

B>Baton Rouge Advocate

“The most culturally and historically significant Jewish foods. . . . Yes, it’s highly debatable—that’s the point.”

B>Epicurious

“Downright entertaining . . . the most interesting cookbook we’ve read this year.”

B>Fleishigs Magazine

“You, me, your grandparents, your nosy neighbors and your jealous non-Jewish foodie friends all need to pick up a copy of The 100 Most Jewish Foods: A Highly Debatable List. . . . This ain’t just a cookbook. It’s also a history lesson, a culinary compendium and a gorgeously photographed gourmet grab bag. By dissecting various meals or foodstuffs, this book has captured the very essence of what it means to be Jewish.”

B>Baltimore Jewish Living

“You don’t have to be Jewish to love The 100 Most Jewish Foods. . . . Funny, emotional, memorable, and filled with gemutlichkeit, this is a book for any reason and all seasons.”

B>Booklist, starred review

“This entertaining and informative reference brings the rich traditions of Jewish foods to life.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use