Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

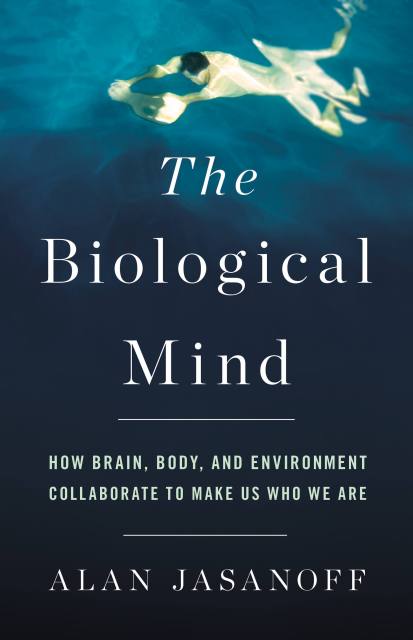

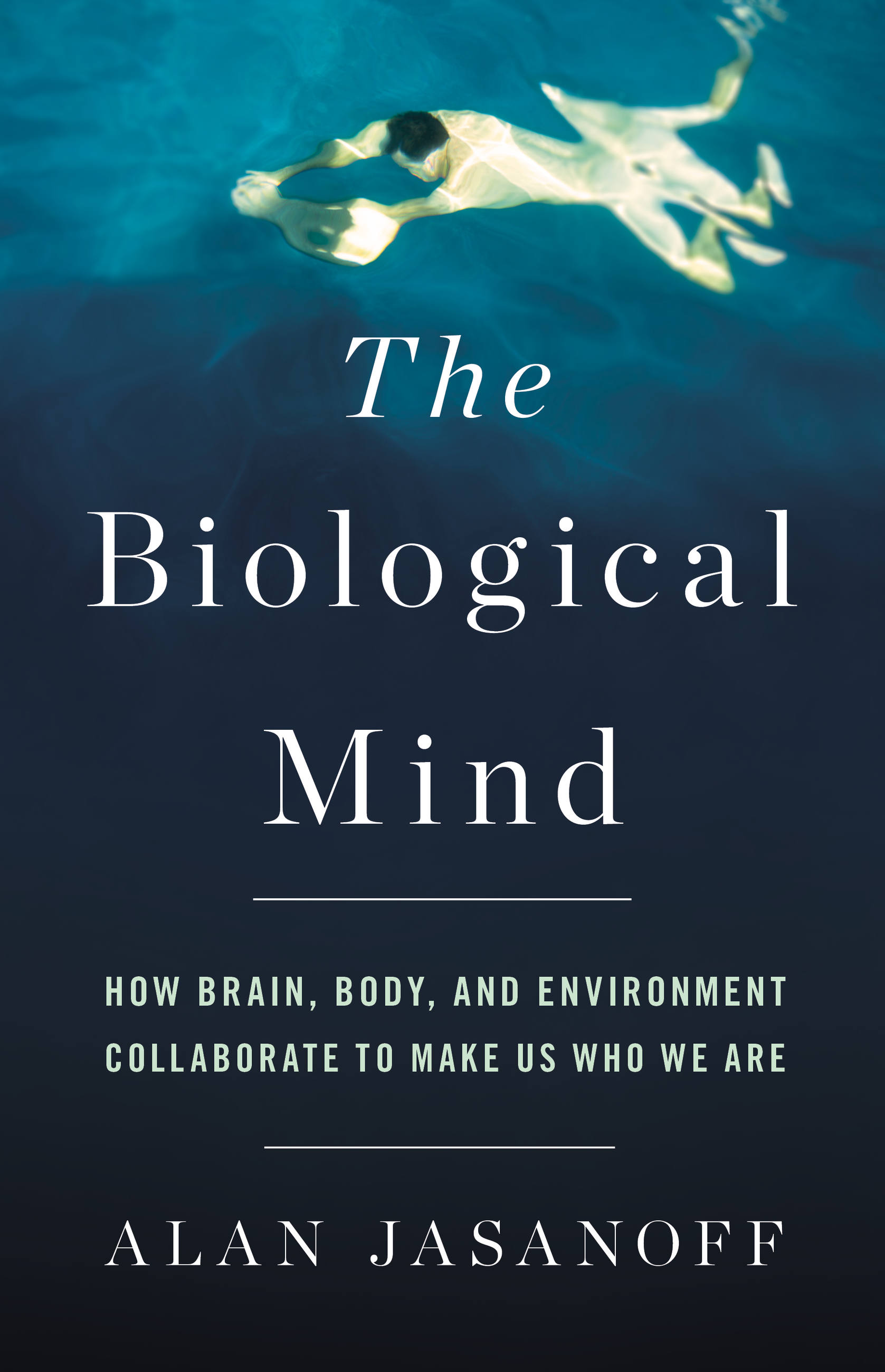

The Biological Mind

How Brain, Body, and Environment Collaborate to Make Us Who We Are

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 13, 2018

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541644311

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 13, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

To many, the brain is the seat of personal identity and autonomy. But the way we talk about the brain is often rooted more in mystical conceptions of the soul than in scientific fact. This blinds us to the physical realities of mental function. We ignore bodily influences on our psychology, from chemicals in the blood to bacteria in the gut, and overlook the ways that the environment affects our behavior, via factors varying from subconscious sights and sounds to the weather. As a result, we alternately overestimate our capacity for free will or equate brains to inorganic machines like computers. But a brain is neither a soul nor an electrical network: it is a bodily organ, and it cannot be separated from its surroundings. Our selves aren’t just inside our heads — they’re spread throughout our bodies and beyond. Only once we come to terms with this can we grasp the true nature of our humanity.