Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

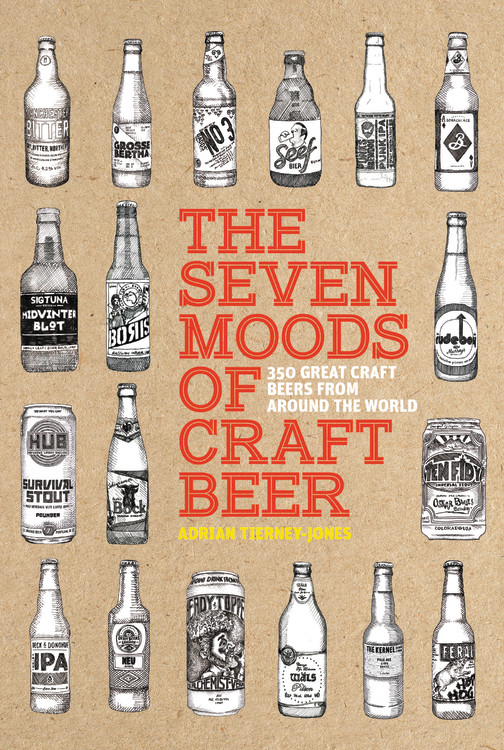

The Seven Moods of Craft Beer

350 Great Craft Beers from Around the World

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $11.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 24, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The Seven Moods of Craft Beer brings together the best 350 beers from around the world and then divides them into specific moods meant as the perfect guide for what to drink, when.

There are beers that are social, like Funky Buddha Hope Gun from Florida, which are to be sipped in the backyard to the hum of conversation and kids playing. There are beers that are imaginative, like the Broken Dream from the UK, meant for contemplative nights with old friends. And there are gastronomic beers, like Sovina which pairs perfectly with a carnitas taco.

Each of the seven chapters offers profiles of approximately 50 beers that cover tasting notes, history and information on the brewery, and alcohol percentage. Sidebars throughout include histories of the world’s best bars and information on styles of beer, brewers and breweries, and the world’s most famous festivals.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 24, 2018

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780316516228

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use