By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

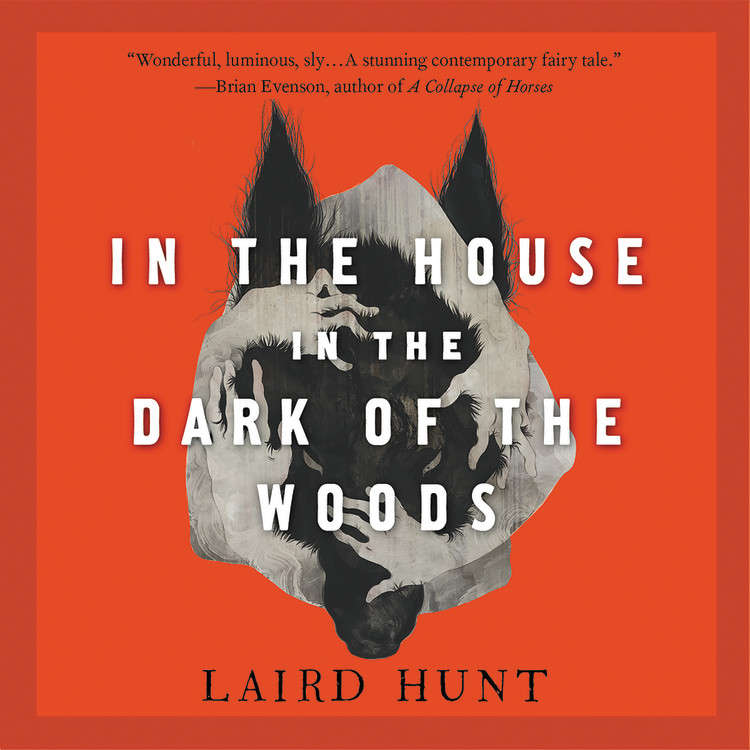

In the House in the Dark of the Woods

Contributors

Read by Vanessa Johansson

By Laird Hunt

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 16, 2018

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478995845

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 16, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The eerie, disturbing story of one of our perennial fascinations — witchcraft in colonial America — wrapped up in a lyrical novel of psychological suspense.

“Once upon a time there was and there wasn’t a woman who went to the woods.” In this horror story set in colonial New England, a law-abiding Puritan woman goes missing. Or perhaps she has fled or abandoned her family. Or perhaps she’s been kidnapped, and set loose to wander in the dense woods of the north. Alone and possibly lost, she meets another woman in the forest. Then everything changes.

On a journey that will take her through dark woods full of almost-human wolves, through a deep well wet with the screams of men, and on a living ship made of human bones, our heroine may find that the evil she flees has been inside her all along.

In the House in the Dark of the Woods is a novel of psychological horror and suspense told in Laird Hunt’s characteristically lyrical prose style. It is the story of a bewitching, a betrayal, a master huntress and her quarry. It is a story of anger, of evil, of hatred and of redemption. It is the story of a haunting, a story that makes up the bedrock of American mythology, told in a vivid way you will never forget.

“Once upon a time there was and there wasn’t a woman who went to the woods.” In this horror story set in colonial New England, a law-abiding Puritan woman goes missing. Or perhaps she has fled or abandoned her family. Or perhaps she’s been kidnapped, and set loose to wander in the dense woods of the north. Alone and possibly lost, she meets another woman in the forest. Then everything changes.

On a journey that will take her through dark woods full of almost-human wolves, through a deep well wet with the screams of men, and on a living ship made of human bones, our heroine may find that the evil she flees has been inside her all along.

In the House in the Dark of the Woods is a novel of psychological horror and suspense told in Laird Hunt’s characteristically lyrical prose style. It is the story of a bewitching, a betrayal, a master huntress and her quarry. It is a story of anger, of evil, of hatred and of redemption. It is the story of a haunting, a story that makes up the bedrock of American mythology, told in a vivid way you will never forget.

-

A New York Times Book ReviewEditors' Choice

-

"[Hunt] has fashioned an edge of-the-seat experience more akin to watching a horror movie. Don't go in the cellar! Don't eat that pig meat! Darkness is everywhere. . . . So prepare yourself. This is a perfect book to read when you're safely tucked in your home, your back to the wall, while outside your door the wind rips the leaves from the trees and the woods grow dark."New York Times Book Review

-

"Engrossing... a game abundant in mysteries but scant in resolutions. The book's greatest strength is its striking, sensual prose."The New Yorker

-

"Like Richard Hughes' In Hazard or Arthur Machen's 'The White People,' Hunt's In the House in the Dark of the Woods tells a dark story brightly, leading the reader to see and sense the things that the protagonist isn't saying, and maybe can't even acknowledge. A wonderful, luminous, sly tale that orbits around a very grim core, growing darker and darker as it goes. A stunning contemporary fairy tale."Brian Evenson, author of A Collapse of Horses

-

'"A dark treat of a novel: lush, exciting and gorgeously strange."Sarah Waters

-

"I adored this book and found it to be entirely spellbinding and scary and strange... It carries us along in a current of intoxicating dread, bearing witness to one woman's dreamlike journey of the soul."Mona Awad, author of 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl

-

"A thrilling, magical tale that straddles two worlds: the harsh, at times grim reality of colonial New England, and the imaginative shadow world from which the oldest fairy tales are woven."Kathleen Kent, bestselling author of The Heretic's Daughter

-

"With the surprise of fairy tale and fable but with the complexity of one's favorite literary novel, Laird Hunt again gives us fierce, complex women living in American history."TaraShea Nesbit, author of The Wives of Los Alamos

-

"Hunt's accomplished prose creates the atmosphere of possibility and danger that lurks in the best fairy tales, where anything can happen but everything has a cost. Highly recommended for fans of that amorphous border between fantasy, horror, and literary fiction as found in the work of Kelly Link, in Joy Williams' The Changeling (1978), or in Angela Carter's The Bloody Chamber (1979)."Booklist, Starred Review

-

"The eerie, disturbing story of one of our perennial fascinations--witchcraft in colonial America--wrapped up in a lyrical novel of psychological suspense."BookBub

-

"It's tough to give a simple description of this book, except to say that it tackles witchcraft in colonial America, providing a mythology that's sure to disturb."Bookriot

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use