By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

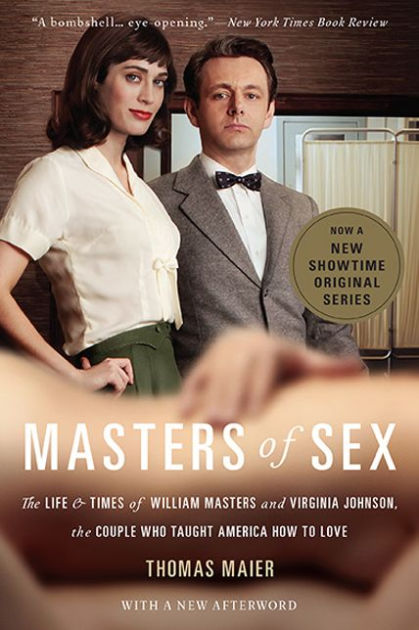

Masters of Sex

The Life and Times of William Masters and Virginia Johnson, the Couple Who Taught America How to Love

Contributors

By Thomas Maier

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 30, 2013

- Page Count

- 440 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465079995

Price

$24.99Price

$32.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback (Media Tie-In) $24.99 $32.99 CAD

- ebook (Media Tie-In) $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 30, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Showtime’s dramatic series Masters of Sex, starring Michael Sheen and Lizzy Caplan, is based on this real-life story of sex researchers William Masters and Virginia Johnson. Before Sex and the City and ViagraTM, America relied on Masters and Johnson to teach us everything we needed to know about what goes on in the bedroom. Convincing hundreds of men and women to shed their clothes and copulate, the pair were the nation’s top experts on love and intimacy. Highlighting interviews with the notoriously private Masters and the ambitious Johnson, critically acclaimed biographer Thomas Maier shows how this unusual team changed the way we all thought about, talked about, and engaged in sex while they simultaneously tried to make sense of their own relationship. Entertaining, revealing, and beautifully told, Masters of Sex sheds light on the eternal mysteries of desire, intimacy, and the American psyche.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use