Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

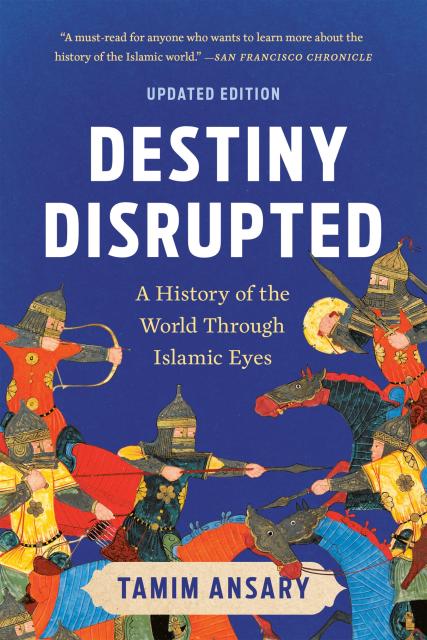

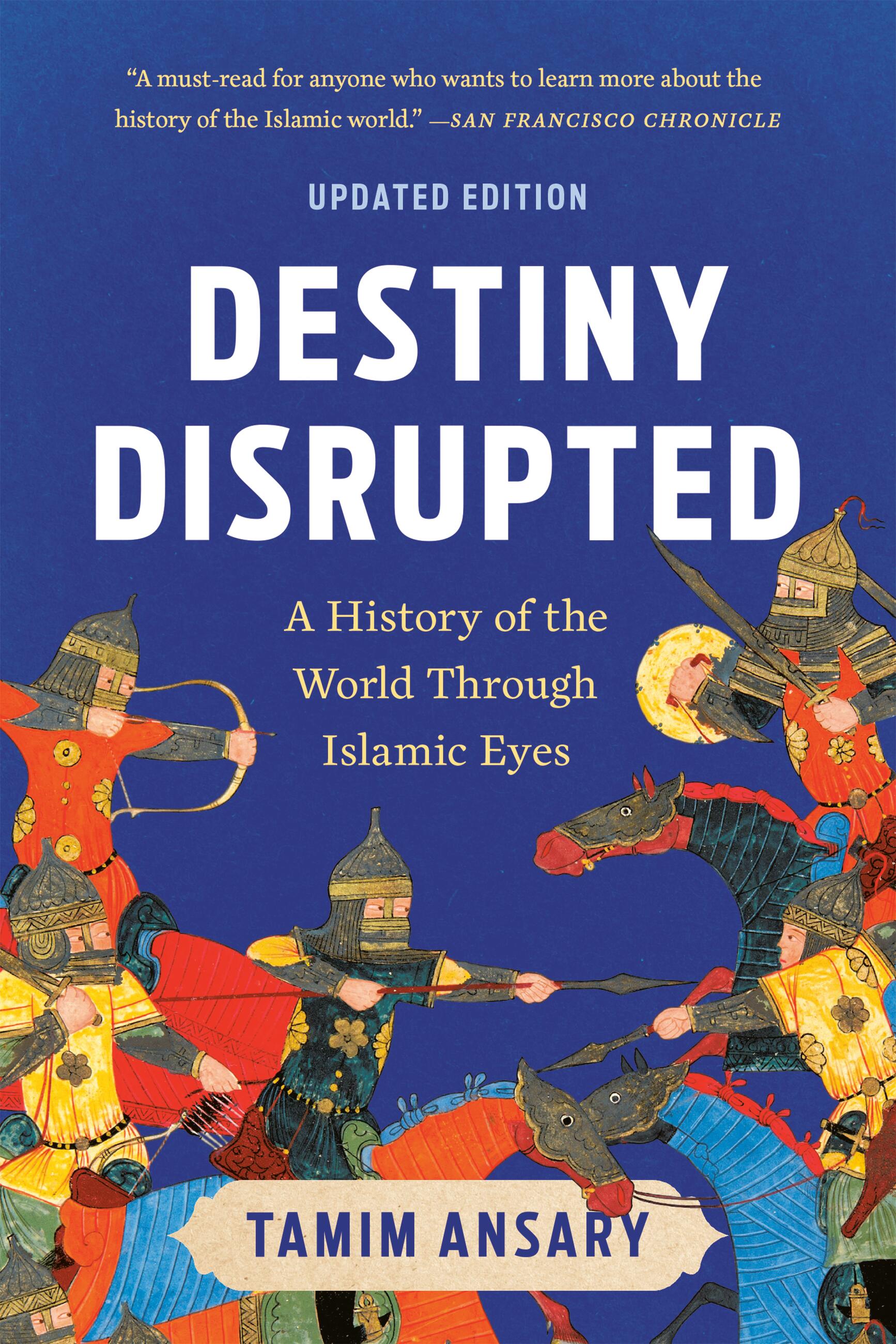

Destiny Disrupted

A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

Contributors

By Tamim Ansary

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 28, 2009

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786741502

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

- Trade Paperback (Revised) $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 28, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In Destiny Disrupted, Tamim Ansary tells the rich story of world history with the evolution of the Muslim community at the center. His story moves from the lifetime of Mohammed through a succession of far-flung empires, to the tangle of modern conflicts that culminated in the events of 9/11. He introduces the key people, events, ideas, legends, religious disputes, and turning points of world history, imparting not only what happened but how it is understood from the Muslim perspective.

He clarifies why two great civilizations—Western and Muslim—grew up oblivious to each other, what happened when they intersected, and how the Islamic world was affected by its slow recognition that Europe—a place it long perceived as primitive—had somehow hijacked destiny.

With storytelling brio, humor, and evenhanded sympathy to all sides of the story, Ansary illuminates a fascinating parallel to the narrative usually heard in the West. Destiny Disrupted offers a vital perspective on world conflicts many now find so puzzling.

Genre:

-

"Ansary has written an informative and thoroughly engaging look at the past, present and future of Islam. With his seamless and charming prose, he challenges conventional wisdom and appeals for a fuller understanding of how Islam and the world at large have shaped each other. And that makes this book, in this uneasy, contentious post 9/11 world, a must-read."Khaled Hosseini, author of The Kite Runner and A Thousand Splendid Suns

-

"A must-read for anyone who wants to learn more about the history of the Islamic world. But the book is more than just a litany of past events. It is also an indispensable guide to understanding the political debates and conflicts of today, from 9/11 to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, from the Somali pirates to the Palestinian/Israeli conflict. As Ansary writes in his conclusion, "The conflict wracking the modern world is not, I think, best understood as a 'clash of civilizations.' ... It's better understood as the friction generated by two mismatched world histories intersecting."San Francisco Chronicle

-

"I'm in the middle of Tamim Ansary's Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World through Islamic Eyes, and it's incredibly illuminating. Ansary pretty much covers the entire history of Islam in an incredibly readable and lucid way. I've been recommending this book to everyone I know. Especially when people are looking for a comprehensive-but-approachable way to look at world history through the lens of Islam, there's no better book."Dave Eggers, TheRumpus.net

-

"A lively, thorough and accessible survey of the history of Islam (both the religion and its political dimension) that explores many of the disconnects between Islam and the West."Shelf Awareness