By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

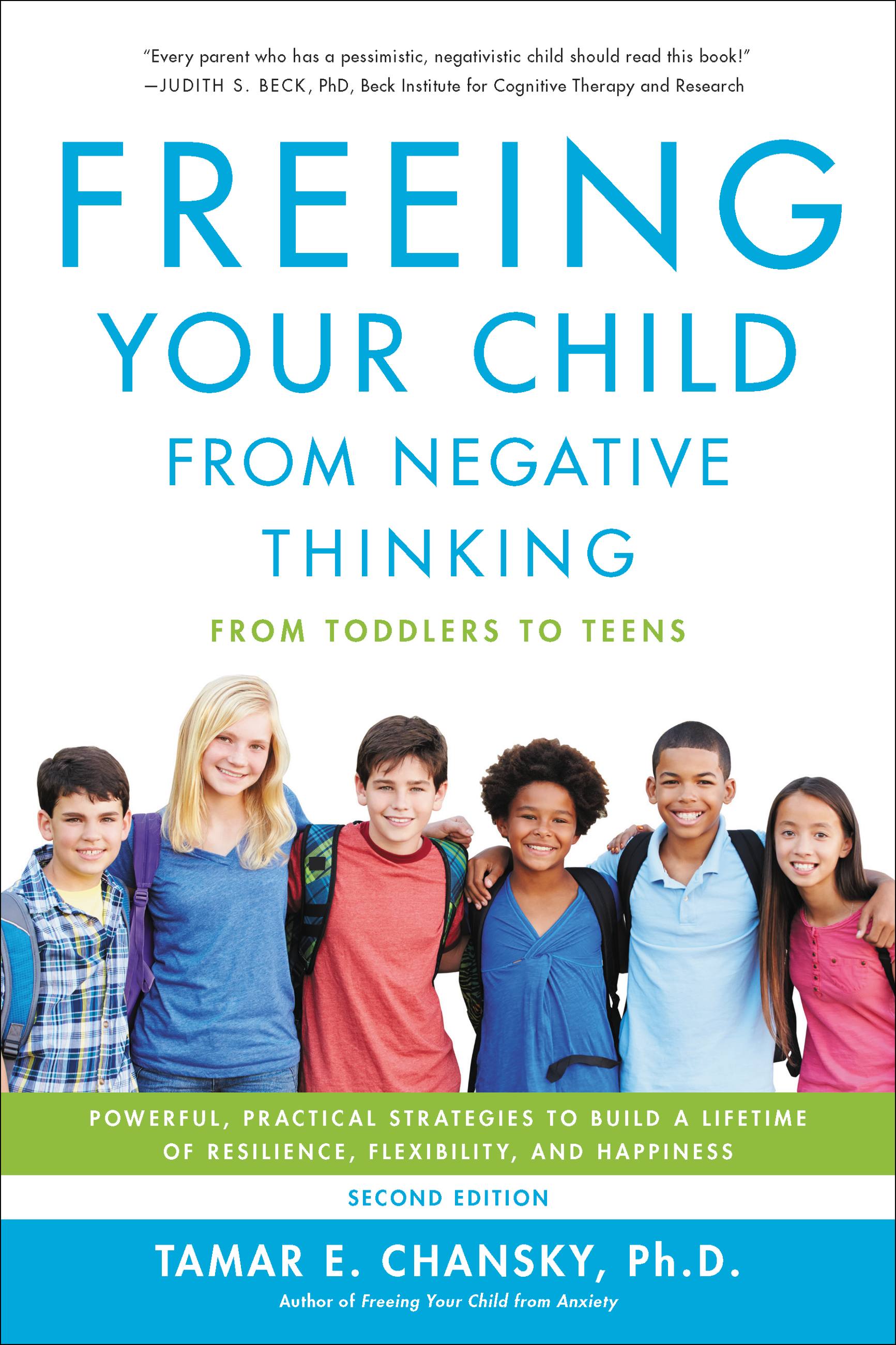

Freeing Your Child from Negative Thinking

Powerful, Practical Strategies to Build a Lifetime of Resilience, Flexibility, and Happiness

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 14, 2020

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Balance

- ISBN-13

- 9780738285962

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 14, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

If unaddressed at the early stages, negative thinking can become the gateway to depression and more serious mental health issues. Habitual negative thinking creates chronic or occasional emotional hurdles and impedes optimism, flexibility, and happiness. Being constantly being overloaded with information from friends, classmates, teachers, parents, and the internet, children need tools and strategies for redirecting negative thoughts when they come. In Freeing Your Child from Negative Thinking, Dr. Chansky provides parents, caregivers, and clinicians with clear, concise, and compassionate guidance in equipping children and teens to overcome negativity. She thoroughly covers the underlying causes of children’s negative attitudes and provides multiple strategies for managing negative thoughts, building optimism, and establishing emotional resilience.

Now, in this revised and updated edition, Dr. Chansky addresses the complex challenges that come with raising kids in a digital age–from navigating social media use to cyber bullying, as well as the grim reality of increased school shootings and suicides. This new edition also includes an expanded section on depression, the importance of healthy sleep, and the parent’s role in their children’s digital lives. With practical tools for parents to guide their children through these challenges, Freeing Your Child from Negative Thinking is the handbook all parents need to help their children cultivate emotional resilience.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use