By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

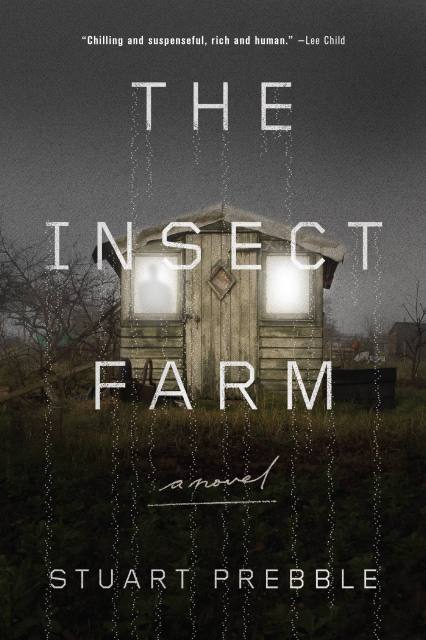

The Insect Farm

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 28, 2017

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Mulholland Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316337380

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 28, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

An eerie debut suspense novel that explores how little one man may know his own brother — and his own mind.

The Maguire brothers each have their own driving, single-minded obsession. For Jonathan, it is his magnificent, talented, and desirable wife, Harriet. For Roger, it is the elaborate universe he has constructed in a shed in their parents’ garden, populated by millions of tiny insects. While Jonathan’s pursuit of Harriet leads him to feelings of jealousy and anguish, Roger’s immersion in the world he has created reveals a capability and talent which are absent from his everyday life.

Roger is known to all as a loving, protective, yet simple man, but the ever-growing complexity of the insect farm suggests that he is capable of far more than anyone believes. Following a series of strange and disturbing incidents, Jonathan begins to question every story he has ever been told about his brother — and if he has so completely misjudged Roger’s mind, what else might he have overlooked about his family, and himself?

The Insect Farm is a dramatic psychological thriller about the secrets we keep from those we love most, and the extent to which the people closest to us are also the most unknowable. In his astounding debut, Stuart Prebble guides us through haunting twists and jolting discoveries as a startling picture emerges: One of the Maguire brothers is a killer, and the other has no idea.

The Maguire brothers each have their own driving, single-minded obsession. For Jonathan, it is his magnificent, talented, and desirable wife, Harriet. For Roger, it is the elaborate universe he has constructed in a shed in their parents’ garden, populated by millions of tiny insects. While Jonathan’s pursuit of Harriet leads him to feelings of jealousy and anguish, Roger’s immersion in the world he has created reveals a capability and talent which are absent from his everyday life.

Roger is known to all as a loving, protective, yet simple man, but the ever-growing complexity of the insect farm suggests that he is capable of far more than anyone believes. Following a series of strange and disturbing incidents, Jonathan begins to question every story he has ever been told about his brother — and if he has so completely misjudged Roger’s mind, what else might he have overlooked about his family, and himself?

The Insect Farm is a dramatic psychological thriller about the secrets we keep from those we love most, and the extent to which the people closest to us are also the most unknowable. In his astounding debut, Stuart Prebble guides us through haunting twists and jolting discoveries as a startling picture emerges: One of the Maguire brothers is a killer, and the other has no idea.

-

"Chilling and suspenseful, rich and human."Lee Child, #1 bestselling author of Personal

-

"Only rarely do a gripping psychological crime story and a literary writer's insight and masterful style coincide. But The Insect Farm has that distinction. You'll read this book fast, so compelling is the story, then--I guarantee--go back and read it again to savor the author's gift for rich, lyrical writing. A tour de force."Jeffery Deaver, bestselling author of Solitude Creek

-

"The opening few pages of The Insect Farm so grabbed me that I couldn't stop reading. This is one of the most original, surprising, and even shocking suspense thrillers that I've come across in a long time."David Morrell, bestselling author of Inspector of the Dead and Murder as a Fine Art

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use