By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

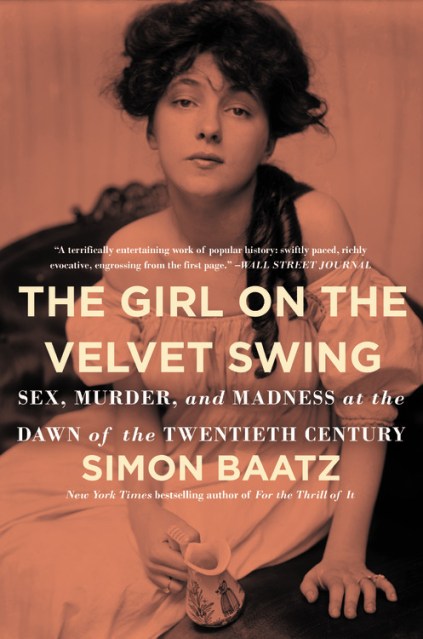

The Girl on the Velvet Swing

Sex, Murder, and Madness at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century

Contributors

By Simon Baatz

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 19, 2019

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Mulholland Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316396660

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 19, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From New York Times bestselling author Simon Baatz, the first comprehensive account of the murder that shocked the world.

In 1901 Evelyn Nesbit, a chorus girl in the musical Florodora, dined alone with the architect Stanford White in his townhouse on 24th Street in New York. Nesbit, just sixteen years old, had recently moved to the city. White was forty-seven and a principal in the prominent architectural firm McKim, Mead & White. As the foremost architect of his day, he was a celebrity, responsible for designing countless landmark buildings in Manhattan. That evening, after drinking champagne, Nesbit lost consciousness and awoke to find herself naked in bed with White. Telltale spots of blood on the bed sheets told her that White had raped her.

She told no one about the rape until, several years later, she confided in Harry Thaw, the millionaire playboy who would later become her husband. Thaw, thirsting for revenge, shot and killed White in 1906 before hundreds of theatergoers during a performance in Madison Square Garden, a building that White had designed.

The trial was a sensation that gripped the nation. Most Americans agreed with Thaw that he had been justified in killing White, but the district attorney expected to send him to the electric chair. Evelyn Nesbit’s testimony was so explicit and shocking that Theodore Roosevelt himself called on the newspapers not to print it verbatim. The murder of White cast a long shadow: Harry Thaw later attempted suicide, and Evelyn Nesbit struggled for many years to escape an addiction to cocaine. The Girl on the Velvet Swing, a tale of glamour, excess, and danger, is an immersive, fascinating look at an America dominated by men of outsize fortunes and by the women who were their victims.

In 1901 Evelyn Nesbit, a chorus girl in the musical Florodora, dined alone with the architect Stanford White in his townhouse on 24th Street in New York. Nesbit, just sixteen years old, had recently moved to the city. White was forty-seven and a principal in the prominent architectural firm McKim, Mead & White. As the foremost architect of his day, he was a celebrity, responsible for designing countless landmark buildings in Manhattan. That evening, after drinking champagne, Nesbit lost consciousness and awoke to find herself naked in bed with White. Telltale spots of blood on the bed sheets told her that White had raped her.

She told no one about the rape until, several years later, she confided in Harry Thaw, the millionaire playboy who would later become her husband. Thaw, thirsting for revenge, shot and killed White in 1906 before hundreds of theatergoers during a performance in Madison Square Garden, a building that White had designed.

The trial was a sensation that gripped the nation. Most Americans agreed with Thaw that he had been justified in killing White, but the district attorney expected to send him to the electric chair. Evelyn Nesbit’s testimony was so explicit and shocking that Theodore Roosevelt himself called on the newspapers not to print it verbatim. The murder of White cast a long shadow: Harry Thaw later attempted suicide, and Evelyn Nesbit struggled for many years to escape an addiction to cocaine. The Girl on the Velvet Swing, a tale of glamour, excess, and danger, is an immersive, fascinating look at an America dominated by men of outsize fortunes and by the women who were their victims.

Genre:

-

"A terrifically entertaining work of popular history: swiftly paced, richly evocative, engrossing from the first page. . . . This vivid retelling of the 1906 murder of Stanford White couldn't be timelier. . . . The murder of Stanford White has been the subject of many other books [but] Baatz's gripping, deeply researched retelling is certain to stand as the definitive version."Harold Schechter, Wall Street Journal

-

"Baatz has resurrected a forgotten saga of lust, lucre and lunacy that would seem improbable if it were merely fiction. . . . This true-life theater is packed with action [and] surprises."David Holahan, USA Today (3 out of 4 stars)

-

"A gripping book that is nearly impossible to put down . . . Baatz has crafted a book that reads more like a novel than a historical tome. Peppered with historical photos and with prose that paints a wonderful picture of New York City at the dawn of the 20th century, The Girl on the Velvet Swing brings the characters to life again."Under the Radar

-

"Readers will appreciate Baatz's exciting, novel-like approach, and those interested in early twentieth-century law especially will enjoy the courtroom scenes."Booklist

-

"Simon Baatz has written a wickedly enjoyable book that enthralled me from start to finish. This multifaceted tale, rendered with an expert's touch, encompasses the aspirations and vices of an entire era."Laurence Bergreen, author of Capone

-

"Simon Baatz, the absolute master of the true crime genre, has written another page-turner. This book has everything, bad behavior in high places, a spectacularly public murder, courtroom drama, a daring escape, even a mother-in-law from hell. It reads like fiction, but it's all real. A wonderful book."John Steele Gordon, author of An Empire of Wealth

-

"Simon Baatz takes readers on the strange and sensational legal odyssey of Harry Thaw, the Pittsburgh millionaire who murdered famed architect Stanford White in 1906. . . Baatz offers a detailed and assiduously researched account of the shocking crime and its aftermath, with a focus on the legal wrangling that dominated two trials."Paula Uruburu, author of American Eve

-

"In his absorbing, well-written, and meticulously researched account of the murder of Stanford White, Simon Baatz delves deeper than ever before into the event's judicial, popular, and psychiatric dimensions and ramifications."Mike Wallace, author of the Pulitzer Prize winning Gotham

-

"The Girl on the Velvet Swing is a must-read, a book that is ceaselessly engaging, one surprise following another, even to the author's final assessment of Stanford White and his relationship to Evelyn Nesbit."Leland Roth, author of American Architecture and the critical study "McKim, Mead & White"

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use