By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

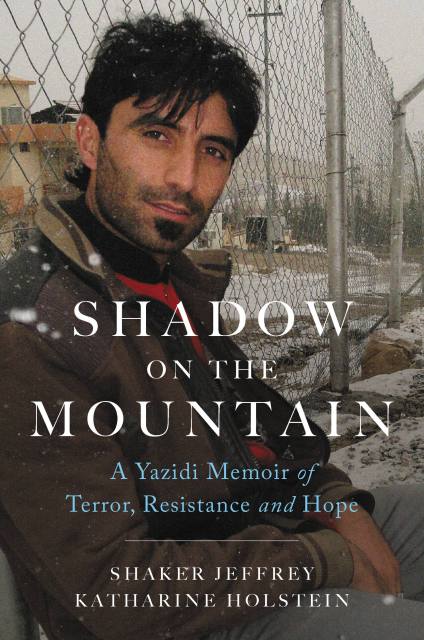

Shadow on the Mountain

A Yazidi Memoir of Terror, Resistance and Hope

Contributors

By Katharine Holstein

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 18, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306922824

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 18, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A powerful and inspiring memoir of a young Yazidi who served as a U.S. combat interpreter but was later forced to flee into the mountains of Iraq to avoid the ISIS slaughter of his people

Shaker’s powerful and inspiring narrative offers a human face to the people and places caught in the crosshairs of a borderless conflict that has come to define our age.

Shaker Jeffrey’s life has been an odyssey of courage, cunning, and desperation. His journey began as a fatherless Iraqi farm boy. As a child he hung out with American troops and practiced his English. Soon he was helping gather information about terrorists, becoming one of the youngest combat interpreters to work for the United States government, even attracting the notice of General Petraeus.

When he was barely sixteen, ISIS overran his Yazidi community and slaughtered most of its people. He narrowly escaped to the mountains with the remnants of his community. But with incredible daring, he became a valuable go-between, informing the U.S. military of the plight of the trapped Yazidis. Time and again he risked his life, going into enemy territory disguised as an ISIS fighter to mount daring rescue operations. Shaker saved over 1,000 civilians from ISIS, including hundreds of girls forced into sex slavery, although he was unable to save his own fiancée from a terrible fate.

-

"A compelling, poignant, and mesmerizing account of the Yazidi people of northwestern Iraq, as seen through the eyes of a young man who experienced the hopes, heartbreaks and tragedies of the past two decades in the 'Land of the Two Rivers.' Shaker Jeffrey and his coauthor Katharine Holstein chronicle Shaker's experiences brilliantly. His innumerable battles with extremists, serious wounds, and ultimately infiltration of ISIS are nothing short of epic and make Shadow on the Mountain an incredible read."General David Petraeus, US Army (Ret), former commander of US Central Command, and former Director of the CIA

-

"A heartrending book that takes us right into the midst of the Yazidi tragedy. This story of one young man offers a powerful insight into what it's like to lose the person and place you love most. A must-read for anyone wants to understand ISIS."Christina Lamb, award-winning chief foreign correspondent for the Sunday Times and coauthor of the bestseller I Am Malala

-

"In Shadow on the Mountain, we follow the harrowing journey of a young Yazidi man fighting the painful ancient destiny of his people. Shaker Jeffrey's spellbinding story of a gruesome era is told in raw and gripping detail. A vital and powerful chronicle of one of the great human tragedies of contemporary history--the savage genocide of a 5,000-year-old peaceful minority in Mesopotamia, the ancient land where humandkind itself was born. A powerful voice that deserves to be heard."Mirza Dinnayi, international human rights activist, Founder of Air Brigade Iraq (Luftbrücke Irak), and the 2019 recipient of the Aurora Prize for Awakening Humanity

-

"[Shaker Jeffrey's] story, powerfully told with coauthor Katharine Holstein, is an incredible saga of selfless and courageous service to his [Yazidi] people and his adopted American brothers as he provided invaluable intelligence and coordination--often personally leading missions behind enemy lines--to help rescue Yazidis from the mountain and the clutches of ISIS. The details that Jeffrey shares about this genocide will bring the toughest reader to tears, and he also illuminates the little-known history and culture of his people. An invaluable look into a still-unfolding tragedy."Booklist, starred review

-

"[A] spellbinding tale woven with gorgeous phrasing, compelling you to finish its journey at a breakneck pace along with Shaker Jeffrey, a hero of Promethean proportions."New York Journal of Books

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use