By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

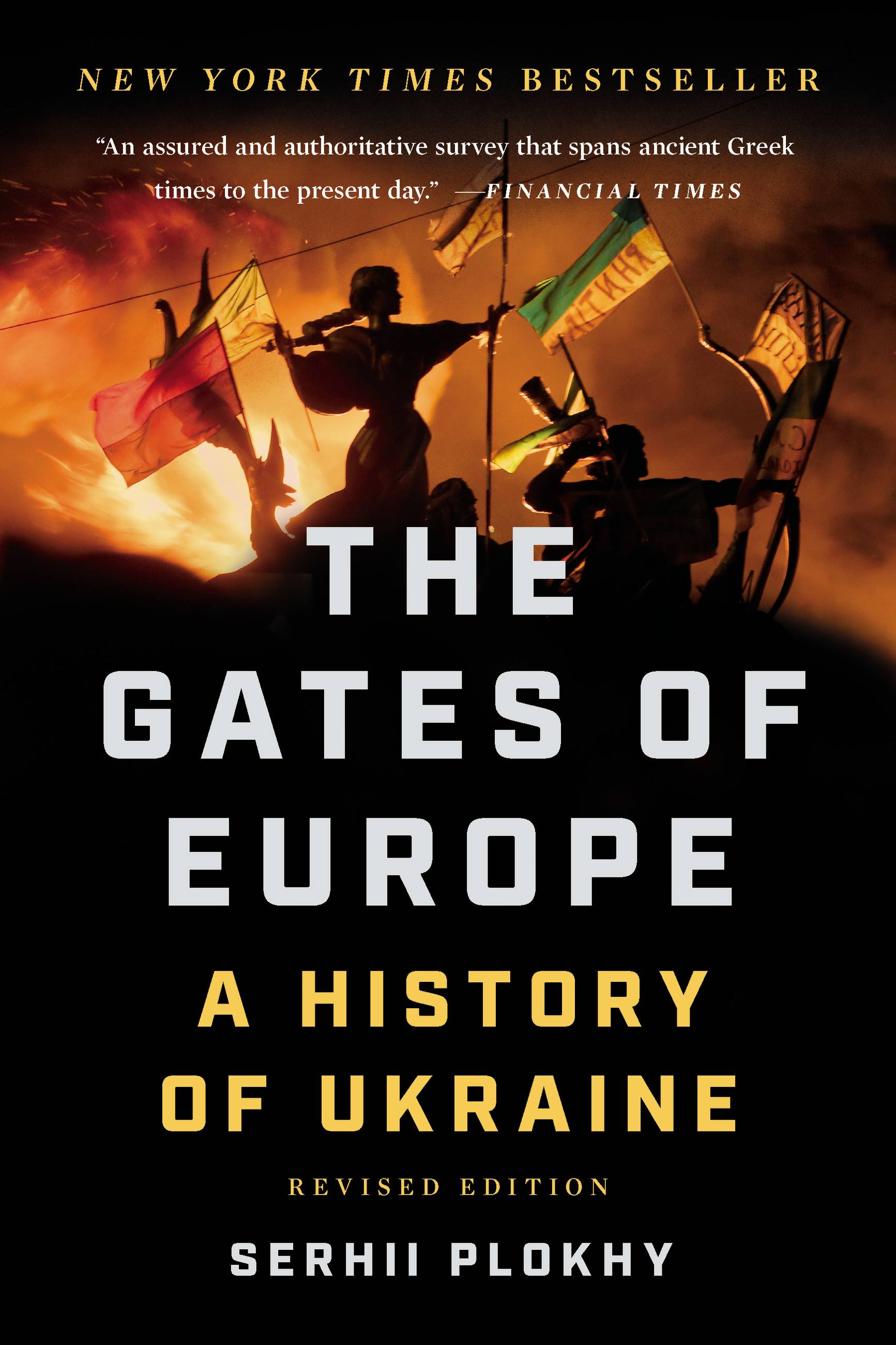

The Gates of Europe

A History of Ukraine

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 30, 2017

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465093465

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback (Revised) $22.99 $29.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 30, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A New York Times bestseller, this definitive history of Ukraine is “an exemplary account of Europe’s least-known large country” (Wall Street Journal).

As Ukraine is embroiled in an ongoing struggle with Russia to preserve its territorial integrity and political independence, celebrated historian Serhii Plokhy explains that today’s crisis is a case of history repeating itself: the Ukrainian conflict is only the latest in a long history of turmoil over Ukraine’s sovereignty. Situated between Central Europe, Russia, and the Middle East, Ukraine has been shaped by empires that exploited the nation as a strategic gateway between East and West—from the Romans and Ottomans to the Third Reich and the Soviet Union. In The Gates of Europe, Plokhy examines Ukraine’s search for its identity through the lives of major Ukrainian historical figures, from its heroes to its conquerors.

This revised edition includes new material that brings this definitive history up to the present. As Ukraine once again finds itself at the center of global attention, Plokhy brings its history to vivid life as he connects the nation’s past with its present and future.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use