Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

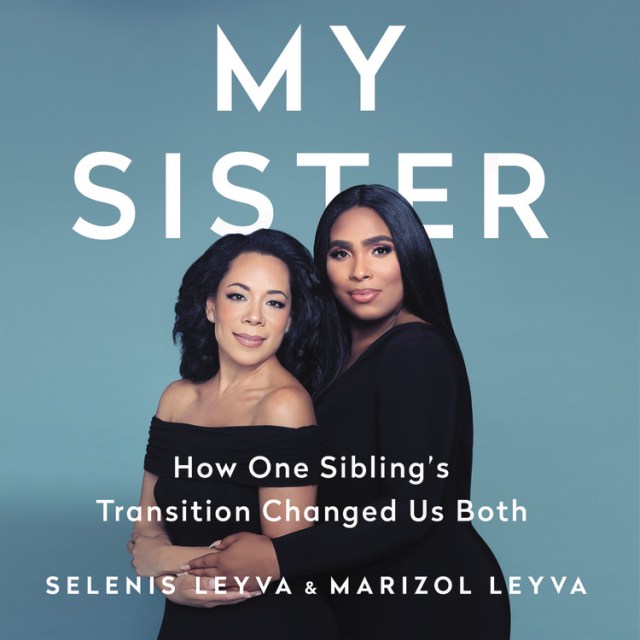

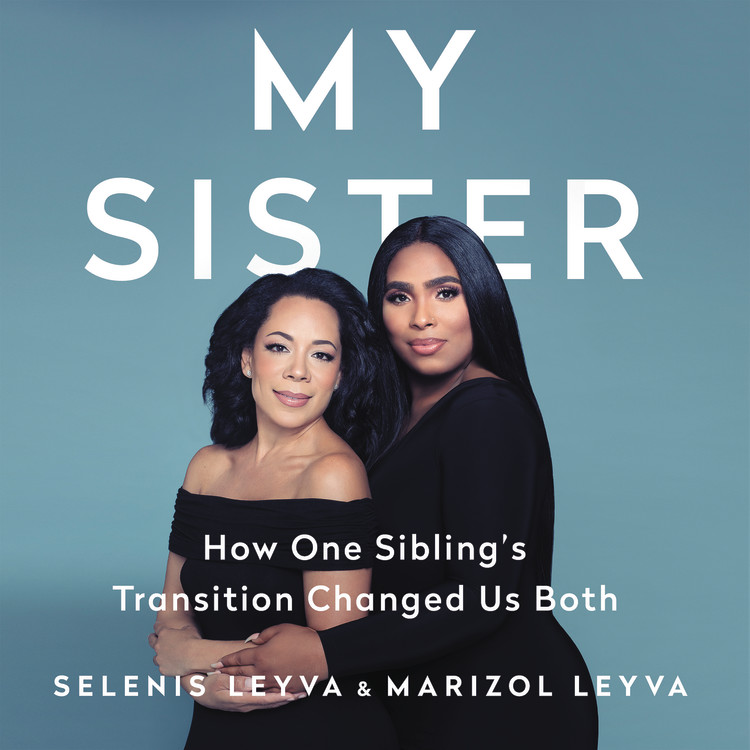

My Sister

How One Sibling's Transition Changed Us Both

Contributors

Read by Selenis Leyva

Read by Marizol Leyva

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 24, 2020

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549148569

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook (Spanish) $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback (Spanish) $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 24, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

When Orange Is the New Black and Diary of a Future President star Selenis Leyva was young, her hardworking parents brought a new foster child into their warm, loving family in the Bronx. Selenis was immediately smitten; she doted on the baby, who in turn looked up to Selenis and followed her everywhere. The little boy became part of the family. But later, the siblings realized that the child was struggling with their identity. As Marizol transitioned and fought to define herself, Selenis and the family wanted to help, but didn’t always have the language to describe what Marizol was going through or the knowledge to help her thrive.

In My Sister, Selenis and Marizol narrate, in alternating chapters, their shared journey, challenges, and triumphs. They write honestly about the issues of violence, abuse, and discrimination that transgender people and women of color–and especially trans women of color–experience daily. And they are open about the messiness and confusion of fully realizing oneself and being properly affirmed by others, even those who love you.

Profoundly moving and instructive, My Sister offers insight into the lives of two siblings learning to be their authentic selves. Ultimately, theirs is a story of hope, one that will resonate with and affirm those in the process of transitioning, watching a loved one transition, and anyone taking control of their gender or sexual identities.

-

"Selenis and Marizol Leyva have crafted a moving and searingly honest portrait of what it means to lead an authentic life. By turns poignant and anguishing, the story of Marizol's journey as she fights to become who she was always meant to be will capture your imagination, but it is the immutable bond between sisters that, in the end, will break your heart."Kate Mulgrew, author of How to Forget and Born with Teeth

-

"The spellbinding fusion of two sisters' fierce voices gives us this groundbreaking memoir about the fight to love and be loved as we are. My Sister is a must read for our fractured era, evoking the power of bridges to knock down the barriers that separate us -- from ourselves and one another. It's fast-paced and beautifully real."Jean Guerrero, Emmy-winning journalist and author of Crux: A Cross-Border Memoir

-

"Fiercely honest, this book not only chronicles a harrowing journey to self-acceptance; it also celebrates an interpersonal love that transcends the bounds of blood and family. Bold, raw, and courageous."Kirkus

-

"[An] unsparingly candid story of one transgender woman's transition."Booklist

-

"Heart-wrenching...What makes My Sister special is not only the way it addresses trans identities with such care -- educating readers in a respectful and non-condescending way -- but also the way it balances a trans person's journey with the corresponding journey that her family must take to embrace her as she is...An important, informative and captivating read that chronicles two strong women learning to love one another."Associated Press