By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

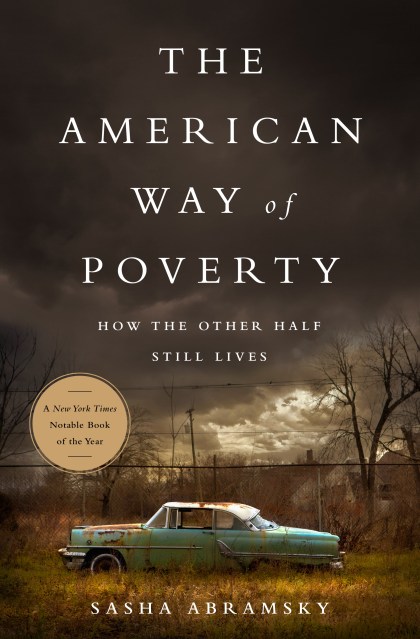

The American Way of Poverty

How the Other Half Still Lives

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 10, 2013

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568589558

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 10, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Fifty years after Michael Harrington published his groundbreaking book The Other America, in which he chronicled the lives of people excluded from the Age of Affluence, poverty in America is back with a vengeance. It is made up of both the long-term chronically poor and new working poor — the tens of millions of victims of a broken economy and an ever more dysfunctional political system. In many ways, for the majority of Americans, financial insecurity has become the new norm.

The American Way of Poverty shines a light on this travesty. Sasha Abramsky brings the effects of economic inequality out of the shadows and, ultimately, suggests ways for moving toward a fairer and more equitable social contract. Exploring everything from housing policy to wage protections and affordable higher education, Abramsky lays out a panoramic blueprint for a reinvigorated political process that, in turn, will pave the way for a renewed War on Poverty.

It is, Harrington believed, a moral outrage that in a country as wealthy as America, so many people could be so poor. Written in the wake of the 2008 financial collapse, in an era of grotesque economic extremes, The American Way of Poverty brings that same powerful indignation to the topic.

-

“[This] portrait of poverty is one of great complexity and diversity, existential loneliness and desperation—but also amazing resilience…Abramsky's well-researched, deeply felt depiction of poverty is eye-opening, and his outrage is palpable. He aims to stimulate discussion, but whether his message provokes action remains to be seen.”

—Kirkus Reviews

"Abramsky's portraits of the poor illustrate three striking points: the isolation, diversity-people with no jobs and people with multiple jobs-and resilience of the poor. Drawing on ideas from a broad array of equality advocates, Abramsky offers detailed policies to address poverty, including reform in education, immigration, energy, taxation, criminal justice, housing, Social Security, and Medicaid, as well as analysis of tax and spending policies that could reduce inequities."

—Booklist

"Sasha Abramsky takes us deep into the long dark night of poverty in America, and it's a harrowing trip. His research and remarkable insights have resulted in a book that is stunning in its intensity."

—Bob Herbert, Distinguished Senior Fellow at Demos and former Op-Ed columnist for the New York Times

"Incisive and necessary, The American Way of Poverty is a call to action."

—Lynn Nottage, Pulitzer-prize-winning playwright -

"Abramsky has written an ambitious book that both describes and prescribes. He reaches across a wised range of issues-including education, housing and criminal justice- in a sweeping panorama of poverty's elements. Assembling them in one volume forces him to be superficial on occasion, but that price is worth paying to get the broad scope... Abramsky has invited serious rethinking and issued a significant call to action."

—David Shipler, New York Times Book Review

"[An] extraordinary book... extremely well researched and thorough..."

—Los Angeles Review of Books

"Abramsky's approach is both heartbreaking in its look at the humans who are affected and inspiring in his explanations of how poverty can be addressed and improved... The American Way of Poverty is likely to cause fear--almost no one is exempt from unplanned disasters--but it is also likely to motivate: there are answers; this country can and should improve. Well researched and documented, Abramsky's eye-opening book should be required reading for all U.S. citizens."

—Shelf Awareness

"[A] searing exposé... Abramsky's is a challenging indictment of an economy in which poverty and inequality at the bottom seem like the foundation for prosperity at the top."

—Publishers Weekly, (starred review)

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use