By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

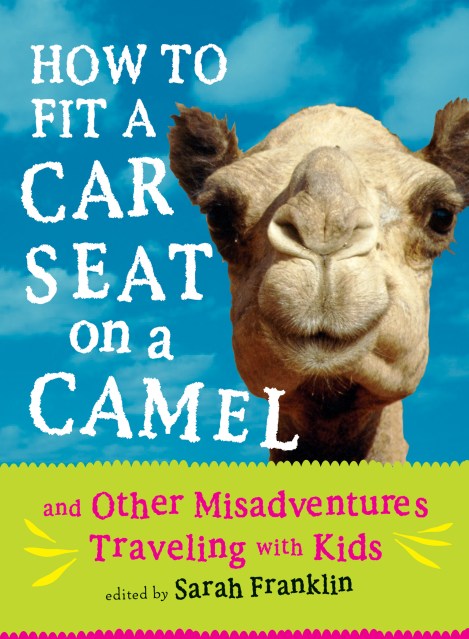

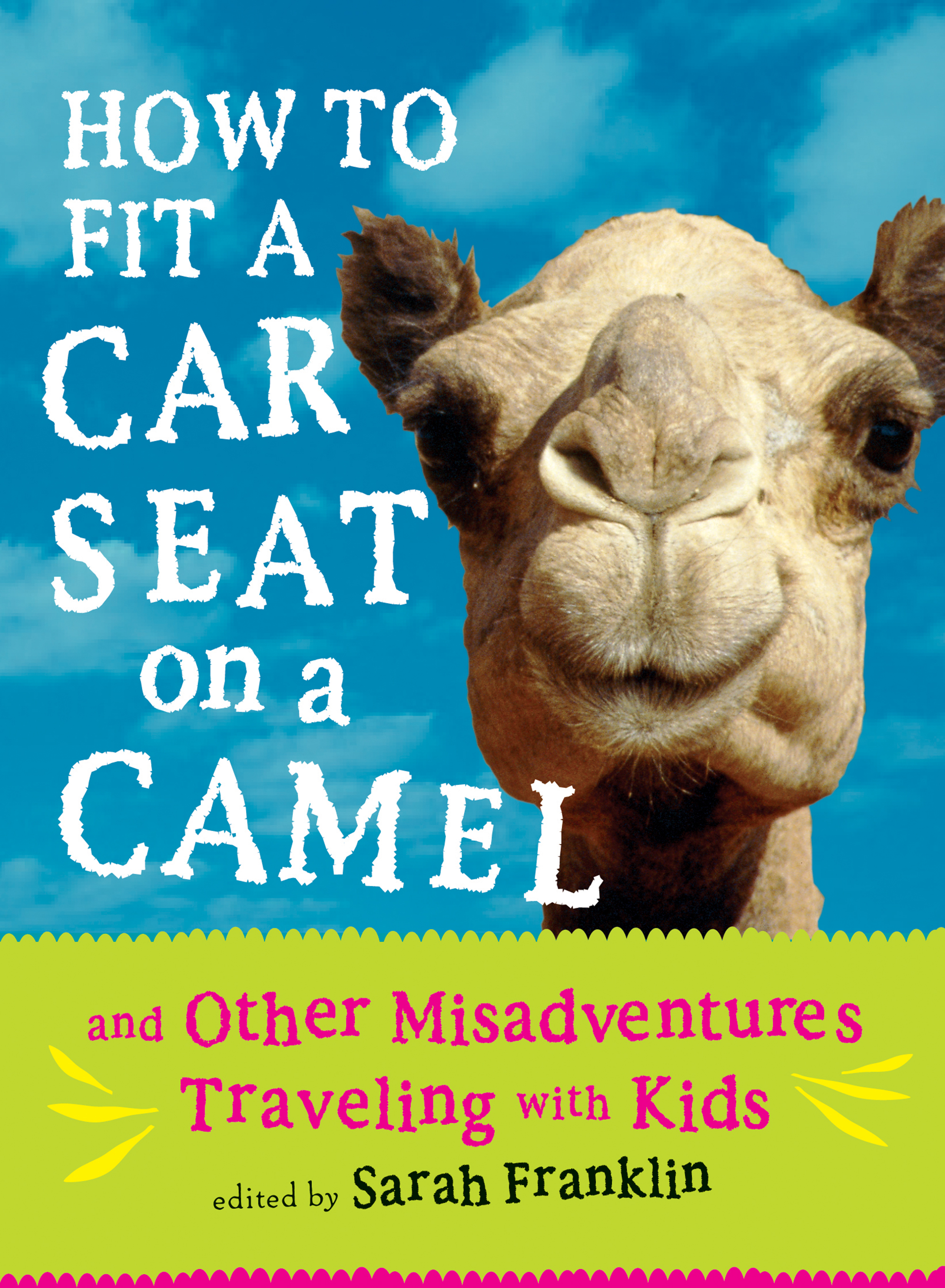

How to Fit a Car Seat on a Camel

And Other Misadventures Traveling with Kids

Contributors

Edited by Sarah Franklin

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 8, 2010

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786750764

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $10.99 $13.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 8, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Have you ever struggled to dislodge a nostril-bound Cheerio while navigating the interstate at 70 miles an hour? Discovered exactly how many renditions of “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” it takes for you to pull the car to the side of the road and weep? Or experienced just what happens when your miniature traveling companion pulls the “manual override” lever on the emergency exit door of a plane? You’re not alone. We all have memories of a hideous yet hilarious family trip.

Now you can read about some that make your trip look like a vacation with the Waltons.

Edited by Sarah Franklin, How to Fit a Car Seat on a Camel is an anthology of outrageous stories about the inherent misadventures that revolve around traveling with kids. Whether the trip is with newborn triplets or with moody teens, a road trip to the beach or a European vacation, each story will resonate with parents who hit the road or the tarmac with kids in tow.

Now you can read about some that make your trip look like a vacation with the Waltons.

Edited by Sarah Franklin, How to Fit a Car Seat on a Camel is an anthology of outrageous stories about the inherent misadventures that revolve around traveling with kids. Whether the trip is with newborn triplets or with moody teens, a road trip to the beach or a European vacation, each story will resonate with parents who hit the road or the tarmac with kids in tow.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use