By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

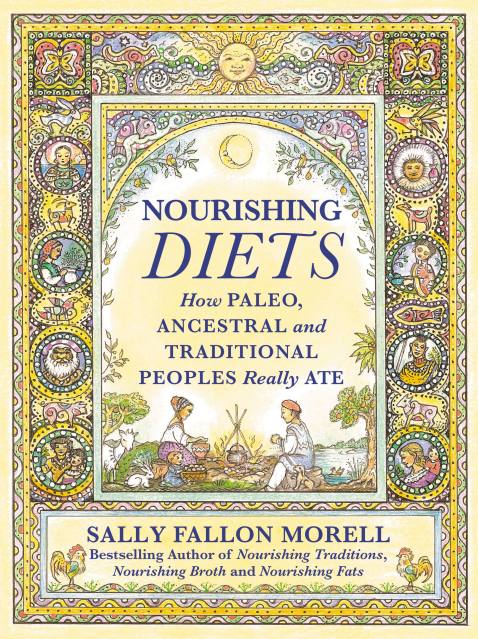

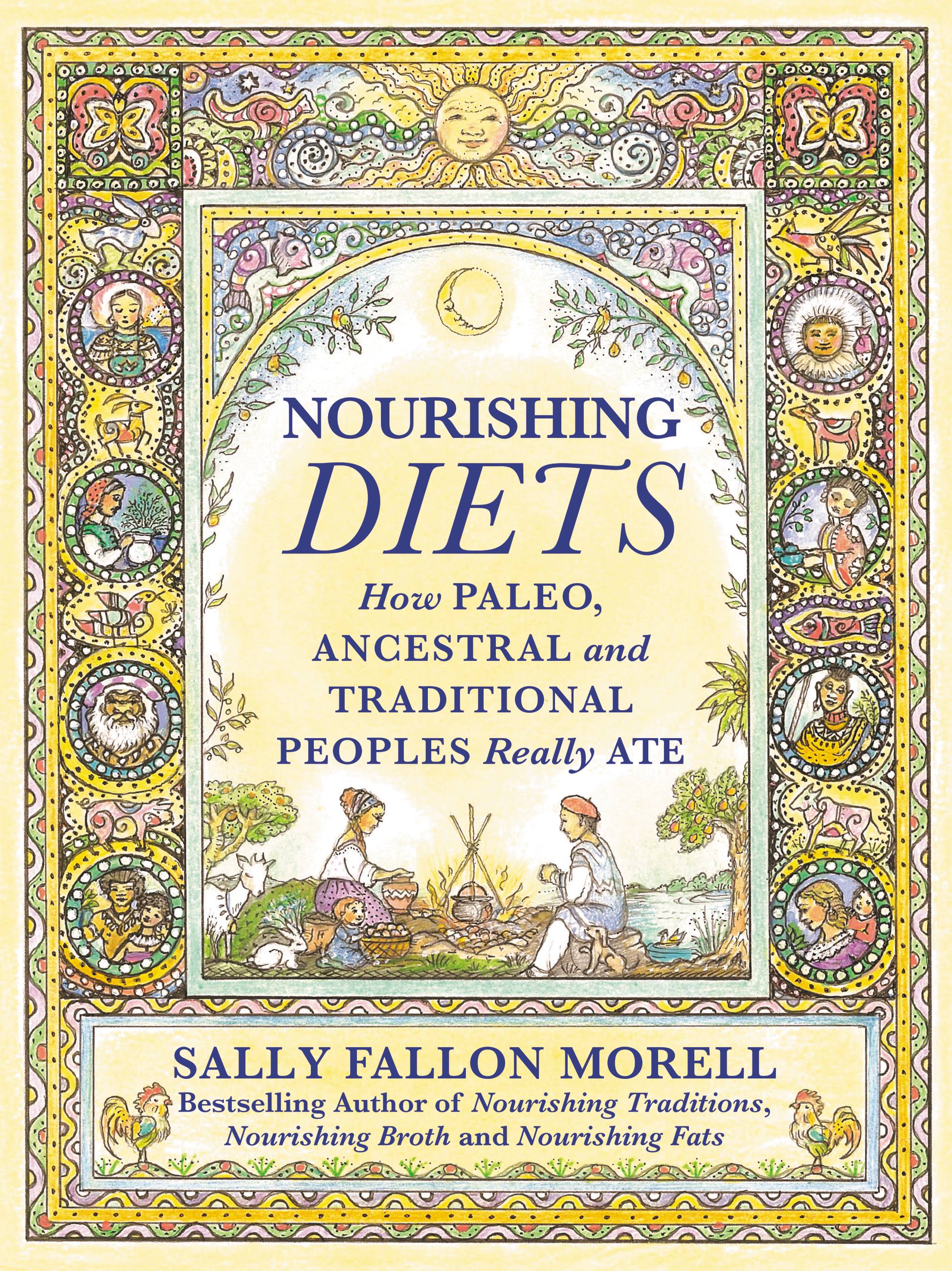

Nourishing Diets

How Paleo, Ancestral and Traditional Peoples Really Ate

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 26, 2018

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Life & Style

- ISBN-13

- 9781538711699

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $25.99 $34.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 26, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Sally Fallon Morell, bestselling author of Nourishing Traditions, debunks diet myths to explore what our ancestors from around the globe really ate–and what we can learn from them to be healthy, fit, and better nourished, today

The Paleo craze has taken over the world. It asks curious dieters to look back to their ancestors’ eating habits to discover a “new” way to eat that shuns grains, most dairy, and processed foods. But, while diet books with Paleo in the title sell well–are they correct? Were paleolithic and ancestral diets really grain-free, low-carb, and based on all lean meat?

In Nourishing Diets bestselling author Sally Fallon Morell explores the diets of our primitive ancestors from around the world–from Australian Aborigines and pre-industrialized Europeans to the inhabitants of “Blue Zones” where a high percentage of the populations live to 100 years or more. In looking to the recipes and foods of the past, Fallon Morell points readers to what they should actually be eating–the key principles of traditional diets from across cultures — and offers recipes to help translate these ideas to the modern home cook.

The Paleo craze has taken over the world. It asks curious dieters to look back to their ancestors’ eating habits to discover a “new” way to eat that shuns grains, most dairy, and processed foods. But, while diet books with Paleo in the title sell well–are they correct? Were paleolithic and ancestral diets really grain-free, low-carb, and based on all lean meat?

In Nourishing Diets bestselling author Sally Fallon Morell explores the diets of our primitive ancestors from around the world–from Australian Aborigines and pre-industrialized Europeans to the inhabitants of “Blue Zones” where a high percentage of the populations live to 100 years or more. In looking to the recipes and foods of the past, Fallon Morell points readers to what they should actually be eating–the key principles of traditional diets from across cultures — and offers recipes to help translate these ideas to the modern home cook.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use