Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

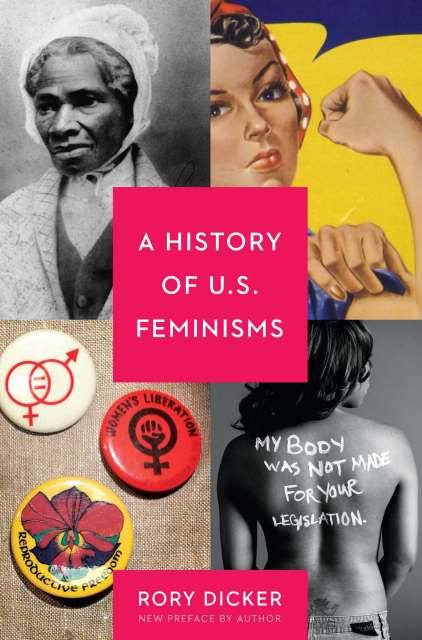

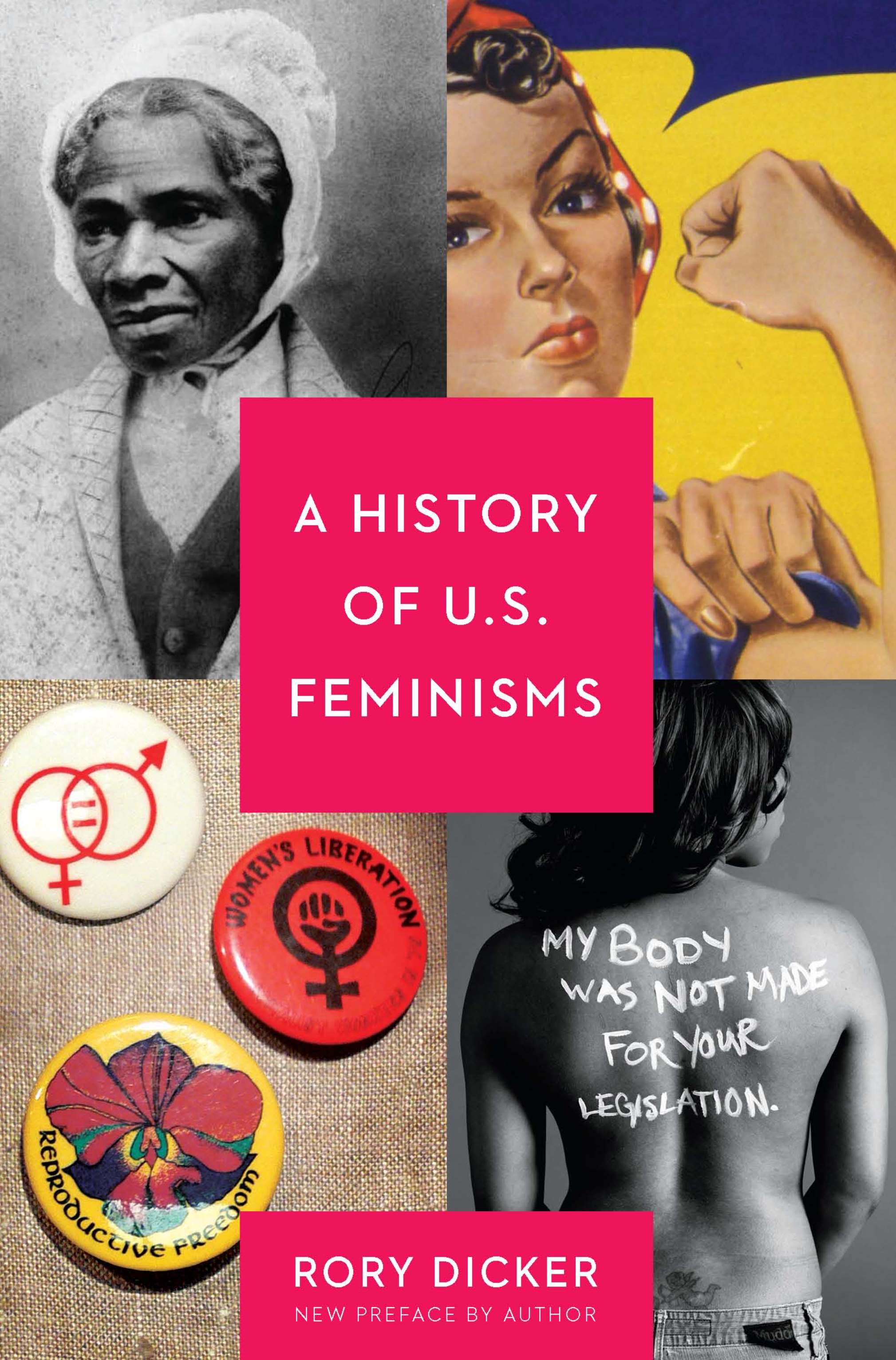

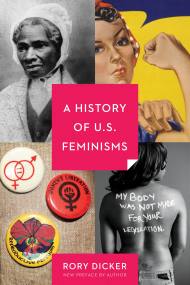

A History of U.S. Feminisms

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 26, 2016

- Page Count

- 200 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580056144

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.98

- Trade Paperback $18.00 $23.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 26, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The complete, authoritative, and up to date history of American feminism-intersectionality, sex-positivity

Updated and expanded, the second edition of A History of U.S. Feminisms is an introductory text that will be used as supplementary material for first-year women’s studies students or as a brush-up text for more advanced students. Covering the first, second, and third waves of feminism, A History of U.S. Feminisms will provide historical context of all the major events and figures from the late nineteenth century through today.

The chapters cover: first-wave feminism, a period of feminist activity during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries which focused primarily on gaining women’s suffrage; second-wave feminism, which started in the ’60s and lasted through the ’80s and emphasized the connection between the personal and the political; and third-wave feminism, which started in the early ’90s and is best exemplified by its focus on diversity, intersectionality, queer theory, and sex-positivity.