Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

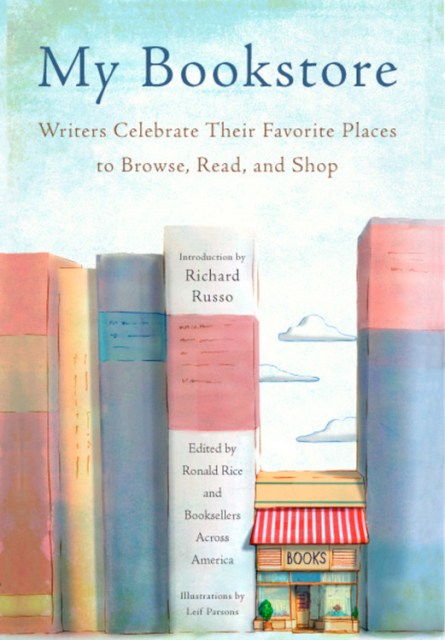

My Bookstore

Writers Celebrate Their Favorite Places to Browse, Read, and Shop

Contributors

Edited by Ronald Rice

Formats and Prices

Price

$23.95Price

$28.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $23.95 $28.95 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $23.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 13, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In My Bookstore our greatest authors write about the pleasure, guidance, and support that their favorite bookstores and booksellers have given them over the years. The relationship between a writer and his or her local store and staff can last for years or even decades. Often it’s the author’s local store that supported him during the early days of his career, that continues to introduce and hand-sell her work to new readers, and that serves as the anchor for the community in which he lives and works.

My Bookstore collects the essays, stories, odes and words of gratitude and praise for stores across the country in 81 pieces written by our most beloved authors. It’s a joyful, industry-wide celebration of our bricks-and-mortar stores and a clarion call to readers everywhere at a time when the value and importance of these stores should be shouted from the rooftops.

Perfectly charming line drawings by Leif Parsons illustrate each storefront and other distinguishing features of the shops.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Nov 13, 2012

- Page Count

- 392 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9781579129101

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use