By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

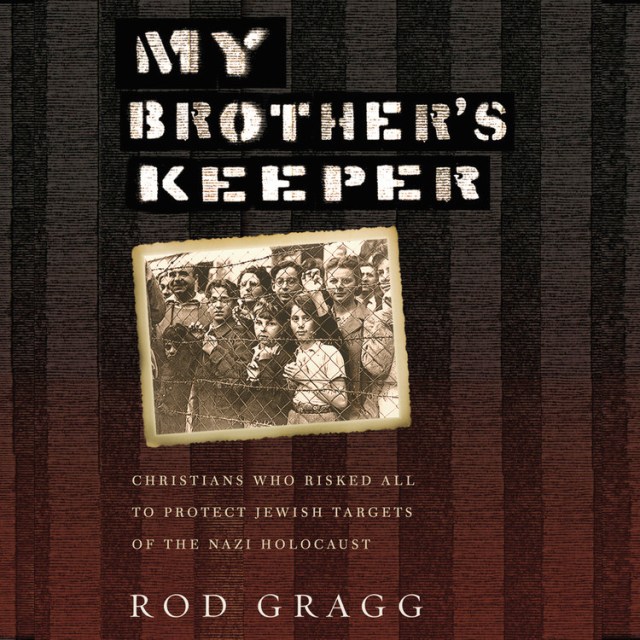

My Brother’s Keeper

Christians Who Risked All to Protect Jewish Targets of the Nazi Holocaust

Contributors

By Rod Gragg

Read by Rick Zieff

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 11, 2016

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478913405

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Hardcover $26.00 $34.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 11, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Thirty captivating profiles of Christians who risked everything to rescue their Jewish neighbors from Nazi terror during the Holocaust.

My Brother’s Keeper unfolds powerful stories of Christians from across denominations who gave everything they had to save the Jewish people from the evils of the Holocaust. This unlikely group of believers, later honored by the nation of Israel as “The Righteous Among the Nations,” includes ordinary teenage girls, pastors, priests, a German army officer, a former Italian fascist, an international spy, and even a princess.

In one gripping profile after another, these extraordinary historical accounts offer stories of steadfast believers who together helped thousands of Jewish individuals and families to safety. Many of these everyday heroes perished alongside the very people they were trying to protect. There is no doubt that all of their stories showcase the best of humanity — even in the face of unthinkable evil.

-

"The Holocaust stands as history's central metaphor for evil. At a time when fear and divisiveness are resurging around the globe, we badly need this harrowing account of unsung heroes who risked all for the sake of good."Philip Yancey, New York Times bestselling author

-

"Gragg provides an inspiring look at 30 Christian heroes who defied the Nazis at great personal risk and bucked the general tide of indifference and paralysis that overwhelmed almost all bystanders to the Holocaust. Jan Karski, who tried to get F.D.R. to respond to the mass murders of Europe's Jews, will be familiar to many readers, but most of the people profiled here are not. For example, relatively few will have heard of Feng Shan Ho, a Chinese Christian, who saved over 12,000 Jews. When Ho's promotion to consul-general at the Chinese embassy in Vienna coincided with increasing reports of Jewish persecution, he issued visas to Austrian and German Jews, allowing them to emigrate to Shanghai. Ho persisted despite opposition by his own government, which wanted to maintain its relationship with Hitler. [...] Gragg gives a sense of these activists' mind-boggling bravery."Publisher's Weekly

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use