By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

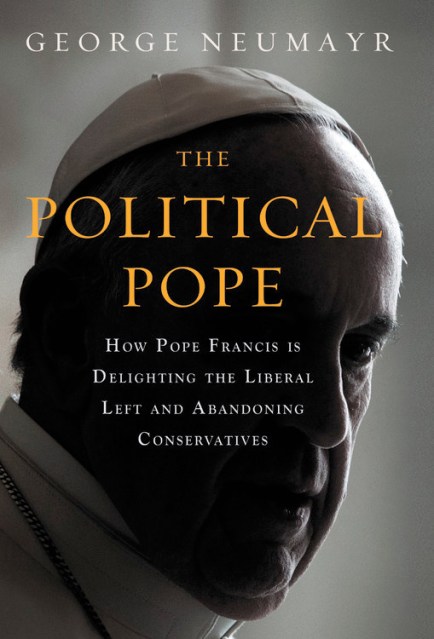

The Political Pope

How Pope Francis Is Delighting the Liberal Left and Abandoning Conservatives

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 2, 2017

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781455570164

Price

$36.00Price

$46.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 2, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Pope Francis is the most liberal pope in the history of the Catholic Church. He is not only championing the causes of the global Left, but also undermining centuries-old Catholic teaching and practice. In the words of the late radical Tom Hayden, his election was “more miraculous, if you will, than the rise of Barack Obama in 2008.”

But to Catholics in the pews, his pontificate is a source of alienation. It is a pontificate, at times, beyond parody: Francis is the first pope to approve of adultery, flirt with proposals to bless gay marriages and cohabitation, tell atheists not to convert, tell Catholics to not breed “like rabbits,” praise the Koran, support a secularized Europe, and celebrate Martin Luther.

At a time of widespread moral relativism, Pope Francis is not defending the Church’s teachings but diluting them. At a time of Christian persecution, he is not strengthening Catholic identity but weakening it. Where other popes sought to save souls, he prefers to “save the planet” and play politics, from habitual capitalism-bashing to his support for open borders and pacifism.

In The Political Pope, George Neumayr gives readers what the media won’t: a bracing look at the liberal revolution that Pope Francis is advancing in the Church. To the radical academic Cornel West, “Pope Francis is a gift from heaven.” To many conservative Catholics, he is the worst pope in centuries.

-

"[A] comprehensive and exhaustive work, a fine example of investigative journalism."Chronicles magazine

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use