Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

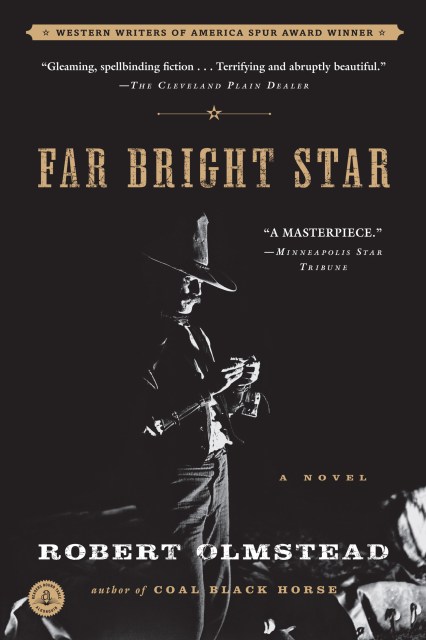

Far Bright Star

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 25, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

"Gleaming, spellbinding fiction . . . Terrifying and abruptly beautiful, the new novel gleams with a masculine intensity; it is hard to read and hard to put down."—The Cleveland Plain Dealer

The year is 1916. The enemy, Pancho Villa, is elusive. Terrain is unforgiving. Through the mountains and across the long dry stretches of Mexico, Napoleon Childs, an aging cavalryman, leads an expedition of inexperienced horse soldiers on seemingly fruitless searches. Though he is seasoned at such missions, things go terribly wrong, and his patrol is suddenly at the mercy of an enemy intent on their destruction. After witnessing the demise of his troops, Napoleon is left by his captors to die in the desert.

Through him we enter the conflicted mind of a warrior as he tries to survive against all odds, as he seeks to make sense of a lifetime of senseless wars and to reckon with the reasons a man would choose a life on the battlefield. Olmstead, an award-winning writer, has created a tightly wound novel that is as moving as it is terrifying.

The year is 1916. The enemy, Pancho Villa, is elusive. Terrain is unforgiving. Through the mountains and across the long dry stretches of Mexico, Napoleon Childs, an aging cavalryman, leads an expedition of inexperienced horse soldiers on seemingly fruitless searches. Though he is seasoned at such missions, things go terribly wrong, and his patrol is suddenly at the mercy of an enemy intent on their destruction. After witnessing the demise of his troops, Napoleon is left by his captors to die in the desert.

Through him we enter the conflicted mind of a warrior as he tries to survive against all odds, as he seeks to make sense of a lifetime of senseless wars and to reckon with the reasons a man would choose a life on the battlefield. Olmstead, an award-winning writer, has created a tightly wound novel that is as moving as it is terrifying.

Genre:

-

“Olmstead delivers another richly characterized, tightly woven story of nature, inevitability and the human condition ... Reminiscent of Kent Haruf, Olmstead’s brilliantly expressive, condensed tale of resilience and dusty determination flows with the kind of literary cadence few writers have mastered.” B>Publishers Weekly, starred reviewPublishers Weekly

-

“Another meditative, beautifully written novel from Olmstead . . . Olmstead is wondrously attuned to the natural world and the realities of war; he uses sand, heat and distant mountains as a stage set, and his narrative unfolds with all the formal rigor of a Greek tragedy . . . Brutal, tender and magnificent.”B>Kirkus Reviews, starred reviewKirkus Reviews

-

"Tautly written and laced with tension . . . Riveting visual effects . . . Olmstead offers a sort of 'thinking-reader's' western . . . Verbal precision and historical accuracy combine with a poetic distillation of a tragic event presented in a solidly captivating reading experience that haunts the mind long after the final page is turned.”The Dallas Morning News

-

"Gleaming, spellbinding fiction . . . Terrifying and abruptly beautiful, the new novel gleams with a masculine intensity; it is hard to read and hard to put down . . . i did succumb, yet again, to the strong spell of Olmstead’s storytelling."The Cleveland Plain Dealer

- On Sale

- May 25, 2010

- Page Count

- 218 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781616200091

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use