Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

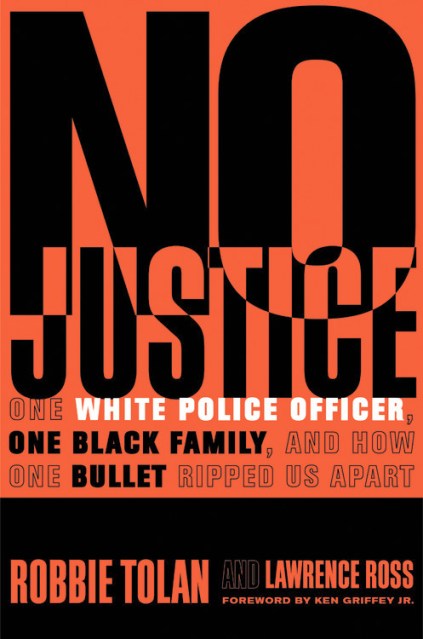

No Justice

One White Police Officer, One Black Family, and How One Bullet Ripped Us Apart

Contributors

By Robbie Tolan

Foreword by Ken Griffey

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 9, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

NO JUSTICE is the harrowing story of Robbie Tolan, who early on one New Year’s Eve morning, found himself being rushed to the hospital. A white police officer had shot him in the chest after mistakenly accusing him of stealing his own car…while in his own driveway.

In a journey that took nearly a decade, Tolan and his family saw his case go before the United States Supreme Court in a groundbreaking decision, while Tolan struggled with how to put his life back together. Holding him together through this journey was the strength of his mother and father, his faith in God, and an impenetrable belief that he deserved justice like any other American who’d been wronged.

NO JUSTICE is the story about what happened after the cameras and social media protests went away. Robbie Tolan was left with the physical and mental devastation from having his body violated by someone who was supposed to serve and protect him. His story reminds us that police brutality is not a theoretical talking point in a larger nationwide argument. This story is about Robbie Tolan courageously picking up the pieces of his life, even as he fights for justice for all.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jan 9, 2018

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781478976653

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use