By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

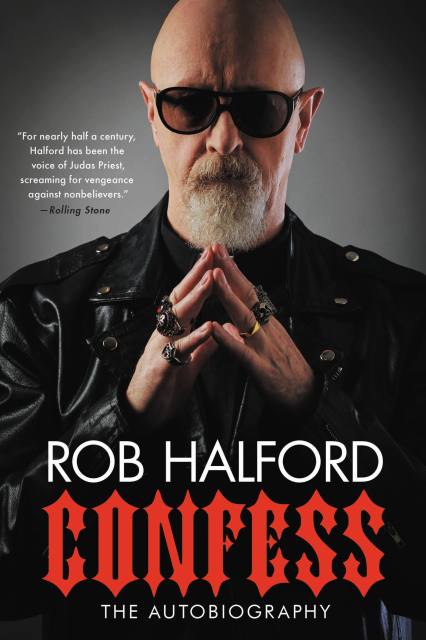

Confess

The Autobiography

Contributors

By Rob Halford

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 29, 2020

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306874956

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 29, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The legendary frontman of Judas Priest, one of the most successful heavy metal bands of all time, celebrates five decades of heavy metal in this tell-all memoir.

Most priests hear confessions. This one is making his.

Rob Halford, front man of global iconic metal band Judas Priest, is a true "Metal God." Raised in Britain's hard-working, heavy industrial heartland, he and his music were forged in the Black Country. Confess, his full autobiography, is an unforgettable rock 'n' roll story-a journey from a Walsall council estate to musical fame via alcoholism, addiction, police cells, ill-fated sexual trysts, and bleak personal tragedy, through to rehab, coming out, redemption . . . and finding love.

Now, he is telling his gospel truth.

Told with Halford's trademark self-deprecating, deadpan Black Country humor, Confess is the story of an extraordinary five decades in the music industry. It is also the tale of unlikely encounters with everybody from Superman to Andy Warhol, Madonna, Jack Nicholson, and the Queen. More than anything else, it's a celebration of the fire and power of heavy metal.

Rob Halford has decided to Confess. Because it's good for the soul.

Named one of the Best Music Books of 2020 by Rolling Stone and Kirkus Reviews

Most priests hear confessions. This one is making his.

Rob Halford, front man of global iconic metal band Judas Priest, is a true "Metal God." Raised in Britain's hard-working, heavy industrial heartland, he and his music were forged in the Black Country. Confess, his full autobiography, is an unforgettable rock 'n' roll story-a journey from a Walsall council estate to musical fame via alcoholism, addiction, police cells, ill-fated sexual trysts, and bleak personal tragedy, through to rehab, coming out, redemption . . . and finding love.

Now, he is telling his gospel truth.

Told with Halford's trademark self-deprecating, deadpan Black Country humor, Confess is the story of an extraordinary five decades in the music industry. It is also the tale of unlikely encounters with everybody from Superman to Andy Warhol, Madonna, Jack Nicholson, and the Queen. More than anything else, it's a celebration of the fire and power of heavy metal.

Rob Halford has decided to Confess. Because it's good for the soul.

Named one of the Best Music Books of 2020 by Rolling Stone and Kirkus Reviews

-

"For nearly half a century, Halford has been the voice of Judas Priest, screaming for vengeance against nonbelievers."Rolling Stone

-

"Rob Halford though is one of the few metal musicians who actually has a story worth hearing....Confess, true to its title, doesn't hold back....Confess manages to be both dark and at times endearing. Halford's openness, despite some dark themes, allows for his humor to shine through....It may have taken a while for Halford to tell his story, but it was certainly worth the wait."New Noise

-

"Raw and searingly moving, Confess will delight metal heads and music fans alike."GQ

-

"Confess can't be reduced to a collection of salacious gay encounters, cocaine binges or romanticized rock'n'roll horror stories. It's a cautionary tale that offers redemption through courage and the changing of times. It's a treasure-trove of heavy metal nuggets and anecdotes that any rock-blog dork would lose their mind over. But most importantly, it's a beautiful exploration of the human condition and one man's capacity for love and self-love."Forbes

-

“Salacious revelations….The most hotly anticipated hard-rock autobiography of the year, Rob Halford’s Confess is gossipy, good natured, and hilarious, often unintentionally. It’s also gloriously and relentlessly filthy….With a breezy, down-to-earth frankness…Confess is much more personal story than music memoir…Halford is winningly unpretentious and self-deprecating….In its final stretches, Confess becomes a moving meditation on family, friendship, personal growth, and social progress…[a] revealing and entertaining book.”Classic Rock Review

-

"[Halford] didn't pull any punches and he didn't leave anything out. I thought that was very courageous...very heartfelt and very real."Buzz Osborne, Melvins

-

"Rob Halford led Judas Priest, and heavy metal itself, out of the Midlands and into the bigtime."The Guardian

-

"Deliciously readable...Confess is a warts-and-all rock'n'roll confessional."Esquire

-

"Confess is no hyperbole: Halford bares his soul."Revolver Magazine

-

"[Halford's] language is vivid and personal...and his tale is compelling. As he tells the story of Judas Priest...he weaves in any number of funny, heartbreaking, and interesting tidbits about the obstacles he encountered and the many famous people he has met along the way."Rolling Stone

-

"Confess is a must-read for Judas Priest fans as it is written from a place of honesty and passion while done with integrity....a page-turner."Sonic Perspectives

-

"Essential reading for any fan of hard rock."Jewish Journal

-

"Whether guiding the reader through the highs and lows of the Judas Priest machine, or through harrowing struggles with his sexuality and cocaine addiction, Halford's ability to let his humble working-class British upbringing and a wisecrack poke through the events depicted in his autobiography, Confess, gives an uplifting aura to even the darkest parts of his life story....It's that sense of introspection that drives what ends up being the most compelling, and inspiring parts of Halford's story....It's the introspective -- and brutal honesty -- of Halford's off-stage struggle that truly lifts his autobiography from a library checkout to a must-purchase."Blabbermouth

-

"Confess digs deeper... and provides useful context."AllMusic.com

-

"Rob Halford has written one of the most candid and surprising memoirs of the year. . . Confess is a riproaring tale, a funny, often shocking and genuinely emotional story."The Telegraph

-

"The Metal God shares stories from a life like no other, spending over 50 years in the heavy metal bubble, facing adversity head-on but always with a wry smile and horns held firmly aloft."Kerrang

-

"A unique and deeply revealing insight into the extraordinary life he has led."Metal Talk

-

"When it comes to metal memoirs, Judas Priest frontman Rob Halford's aptly titled and long-awaited Confess: The Autobiography certainly has enough sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll to satisfy voracious readers of, say, Motley Crüe's The Dirt or Keith Richards's Life. But a great deal of sorrow also permeates the just-released page-turner."Yahoo! News

-

"The Metal God has written his bible."The Oakland Press

-

"A must-read for pop-culture lovers and metalheads alike."The Baltimore Sun

-

"With its courageous, truthful delivery and the depiction of Halford truly rising above difficulties, perhaps the greatest aspect of Confess is the book's ability to inspire readers to rise above their challenges and come out on top. 10/10."Audio Ink Radio

-

"His memoir recounts the highs and lows of his history in a medley of comical, candid, and heartbreaking stories about obstacles and experiences...Confess is a fascinating portrait, dripping in Halford's polite yet brutally honest demeanor and personal slang: equal parts legendary metal icon and every-day humble Walsall lad."Phoenix New Times

-

"Confess...takes readers on a unique journey... Halford is candid and direct."Media Mikes

-

“Free of the demons of his past, Halford chronicles his unique rock and roll journey in this compelling autobiography…. Rock fans will naturally enjoy this book, but it is also a significant contribution to LGBTQIA+ nonfiction.”Library Journal

-

“Rob tells his story without holding anything back. Some truly incredible accounts.”NPR’s Bullseye with Jesse Thorn

-

“The full, frank, and shocking autobiography of Judas Priest's Metal God….[T]his book celebrates five decades of the guts and glory of rock-n-roll.”Rough Trade

-

“An incredibly candid look at one of the biggest metal vocalists of all time….Full of great stories and great jokes.”Metal Injection

-

“The book is well-crafted, detailing Halford's early years and initial forays into the music biz. Fans will love the details of the rise of Priest along with the peaks and valleys along the way…Everything… included helped show a real informative blueprint of [Halford’s] background.”Anti-Music

-

“You can add great writer to [Halford’s] resume as well. His story is incredible and his journey is something that reads like a Hollywood script. Albeit a Quentin Tarantino film….The pages are filled [with] so many great stories and memories – both good and bad. But you get the sense that Halford has always been able to persevere and make the best out of whatever situation he found himself in. And he does this by absolutely keeping the reader entertained with anecdotes and an unbelievable sense of humor.”Sound Vapors

-

“What a rock memoir should be – brutally honest and funny as hell….[Rob Halford] has written a rock memoir so full of life, humor, insight and turmoil that it feels reductive even to assign it to that formulaic genre… complex and richly textured…. While much of the book’s power derives from Halford’s struggle to integrate his public and private lives, there are plenty of beautifully remembered tales of the kind that enliven any rags-to-rock-riches story….A redemptive, funny, honest account…. We all carry secrets. The lesson of this unforgettable memoir is not to let those secrets undo what makes each of us uniquely valuable.”RockandRollGlobe.com

-

“A powerful, often shocking read.”Vintage Guitar

-

“Delivered with refreshing down to earth frankness…Simply put, it's a must read – not only for fans of Halford and Judas Priest, but for all music fans.”Louder

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use