Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

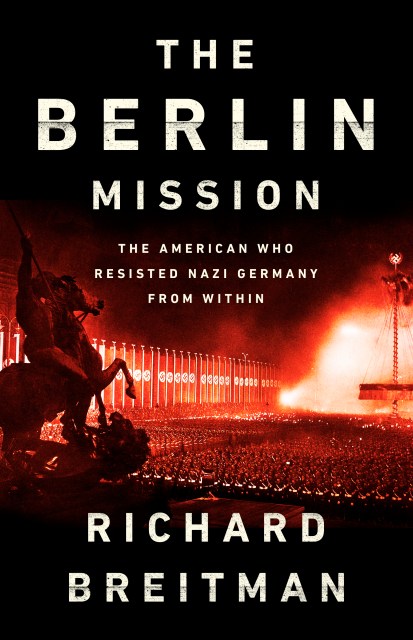

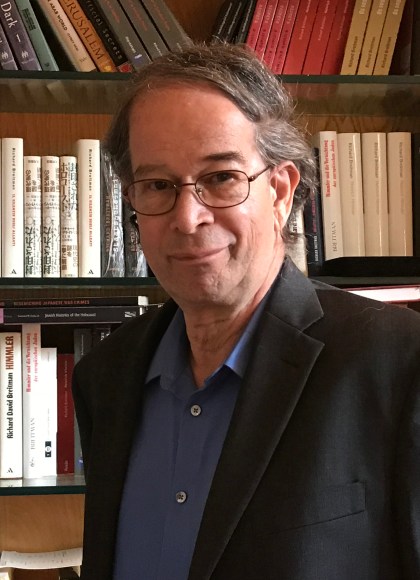

The Berlin Mission

The American Who Resisted Nazi Germany from Within

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 29, 2019

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541742161

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 29, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

An unknown story of an unlikely hero–the US consul who best analyzed the threat posed by Nazi Germany and predicted the horrors to come

In 1929, Raymond Geist went to Berlin as a consul and handled visas for emigrants to the US. Just before Hitler came to power, Geist expedited the exit of Albert Einstein. Once the Nazis began to oppress Jews and others, Geist’s role became vitally important. It was Geist who extricated Sigmund Freud from Vienna and Geist who understood the scale and urgency of the humanitarian crisis.

Even while hiding his own homosexual relationship with a German, Geist fearlessly challenged the Nazi police state whenever it abused Americans in Germany or threatened US interests. He made greater use of a restrictive US immigration quota and secured exit visas for hundreds of unaccompanied children. All the while, he maintained a working relationship with high Nazi officials such as Heinrich Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich, and Hermann Göring.

While US ambassadors and consuls general cycled in and out, the indispensable Geist remained in Berlin for a decade. An invaluable analyst and problem solver, he was the first American official to warn explicitly that what lay ahead for Germany’s Jews was what would become known as the Holocaust.

Genre:

-

"Breitman has...located a 1938 document, published in full as an appendix, which today reads with a terrifying clairvoyance. 'The Germans are determined to solve the Jewish problem without the assistance of other countries, and that means eventual annihilation,' Geist wrote. This, Breitman says, amounts to the first, explicit warning of the coming Holocaust by an American official, and certainly qualifies as the book's most significant contribution to the historical record."James Kirchick, Tablet

-

"Inspiring...This stirring history, which unearths a little-known role model of resistance, will move readers."Publishers Weekly

-

"A vivid chronicle of 1930s Germany conveyed through the life of a lesser-known historical figure."Kirkus Reviews

-

"No American knew Nazi Germany better than Raymond Geist--and no one is better qualified to tell his story than Richard Breitman. As the long-serving US consul in Berlin, Geist served as the trusted intermediary between terrified Jews and their Gestapo tormentors. One of America's leading Holocaust historians, Breitman has skillfully pieced together Geist's extraordinary, largely untold life, including a politically risky homosexual romance. A thrilling read, and a great achievement."Michael Dobbs, author of The Unwanted: America, Auschwitz, and a Village caught in between

-

"In Berlin Mission, Richard Breitman tells us the riveting story of Raymond Geist, an American diplomat stationed in Nazi Germany throughout the pre-war years. Based on entirely new documentation, the book presents the difficult path of an official in charge of visas to the United States, who witnessed and understood the growing plight of German Jews and helped many to reach the American safe haven, notwithstanding a restrictive immigration policy. Geist's efforts became the more crucial as, in early as in December 1938, he deduced from his contacts at the highest ranks of the Gestapo that the Jews remaining under Hitler's domination would ultimately perish. He conveyed his assessment to Washington. In our times of moral uncertainty, this book is a must."Saul Friedländer, professor emeritus in history, UCLA