Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

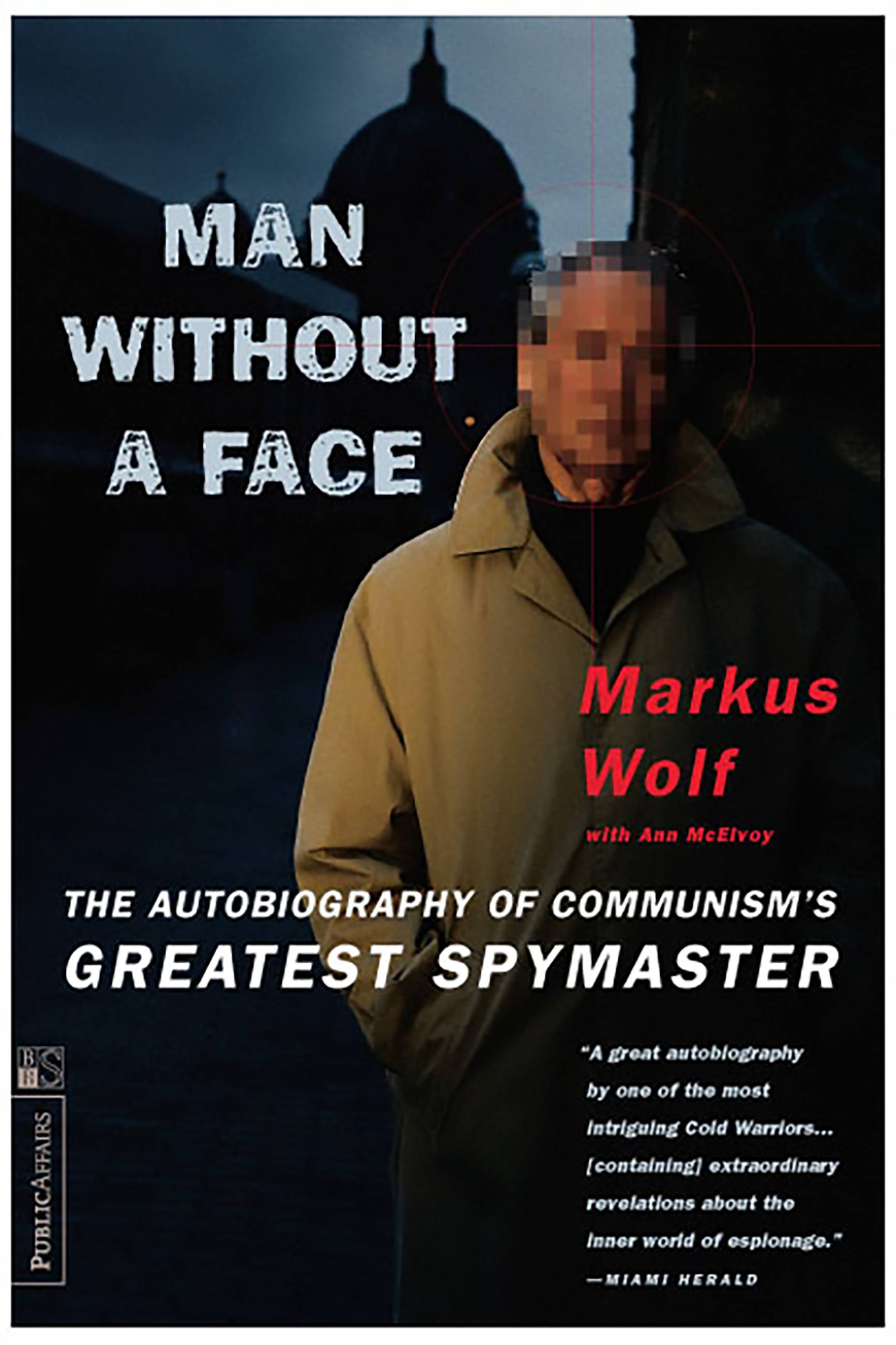

Man Without A Face

The Autobiography Of Communism's Greatest Spymaster

Contributors

By Markus Wolf

By Anne McElvoy

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 4, 1999

- Page Count

- 460 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781891620126

Price

$24.99Price

$31.99 CADFormat

Format:

Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 4, 1999. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

For decades, Markus Wolf was known to Western intelligence officers only as “the man without a face.” Now the legendary spymaster has emerged from the shadows to reveal his remarkable life of secrets, lies, and betrayals as head of the world’s most formidable and effective foreign service ever. Wolf was undoubtedly the greatest spymaster of our century. A shadowy Cold War legend who kept his own past locked up as tightly as the state secrets with which he was entrusted, Wolf finally broke his silence in 1997. Man Without a Face is the result. It details all of Wolf’s major successes and failures and illuminates the reality of espionage operations as few nonfiction works before it. Wolf tells the real story of Gunter Guillaume, the East German spy who brought down Willy Brandt. He reveals the truth behind East Germany’s involvment with terrorism. He takes us inside the bowels of the Stasi headquarters and inside the minds of Eastern Bloc leaders. With its high-speed chases, hidden cameras, phony brothels, secret codes, false identities, and triple agents, Man Without a Face reads like a classic spy thriller—except this time the action is real.