By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

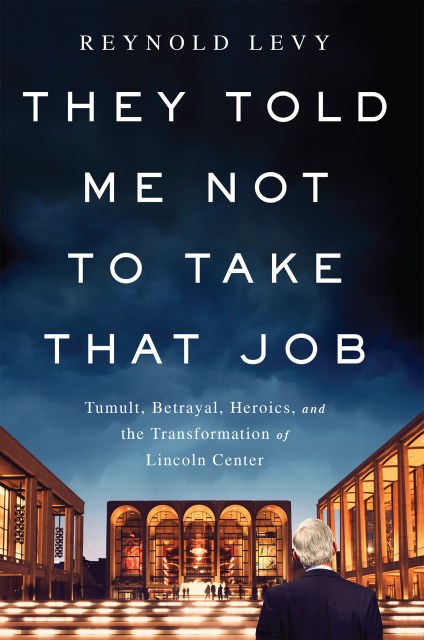

They Told Me Not to Take that Job

Tumult, Betrayal, Heroics, and the Transformation of Lincoln Center

Contributors

By Reynold Levy

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 12, 2015

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610393621

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.99 $36.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 12, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Besides, some of those organizations had daunting problems of their own. Levy tells the inside story of the demise of the New York City Opera, the Metropolitan Opera’s need to use as collateral its iconic Chagall tapestries in the face of mounting operating losses, and the New York Philharmonic’s dalliance with Carnegie Hall.

Yet despite these and other challenges, Levy and the extraordinary civic leaders at his side were able to shape a consensus for the physical modernization of the sixteen-acre campus and raise the money necessary to maintain Lincoln Center as the country’s most vibrant performing arts destination. By the time he left, Lincoln Center had prepared itself fully for the next generation of artists and audiences.

They Told Me Not to Take That Job is more than a memoir of life at the heart of one of the world’s most prominent cultural institutions. It is also a case study of leadership and management in action. How Levy and his colleagues triumphantly steered Lincoln Center — through perhaps the most tumultuous decade of its history to a startling transformation — is fully captured in his riveting account.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use