By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

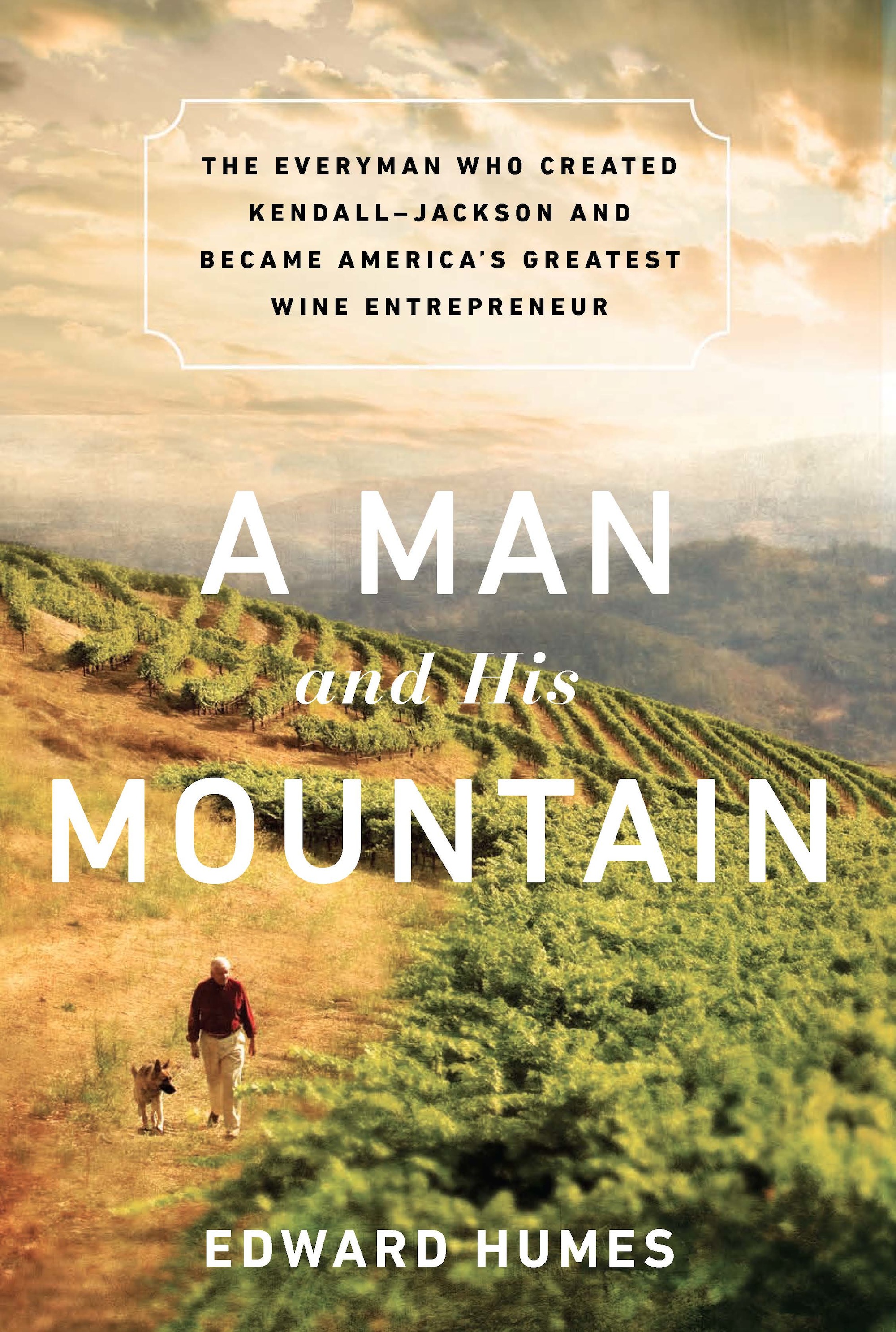

A Man and his Mountain

The Everyman who Created Kendall-Jackson and Became America's Greatest Wine Entrepreneur

Contributors

By Edward Humes

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 22, 2013

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610392860

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $15.99 $20.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 22, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Jess Stonestreet Jackson was one of a small band of pioneering entrepreneurs who put California’s Wine Country on the map. His life story is a compelling slice of history, daring, innovation, feuds, intrigue, talent, mystique, and luck. Admirers and detractors alike have called him the Steve Jobs of wine — a brilliant, infuriating, contrarian gambler who seemed to win more than his share by anticipating consumers’ desires with uncanny skill. Time after time his decisions would be ignored and derided, then envied and imitated as competitors struggled to catch up.

He founded Kendall-Jackson with a single, tiny vineyard and a belief that there could be more to California Wine Country than jugs of bottom-shelf screw-top. Today, Kendall-Jackson and its 14,000 acres of coastal and mountain vineyards produce a host of award-winning wines, including the most popular Chardonnay in the world, which was born out of a catastrophe that nearly broke Jackson. The empire Jackson built endures and thrives as a family-run leader of the American wine industry.

Jess Jackson entered the horseracing game just as dramatically. He brought con men to justice, exposed industry-wide corruption in court and Congress, then exacted the best revenge of all: race after race, he defied conventional wisdom with one high-stakes winner after another, capped by the epic season of Rachel Alexandra, the first filly to win the Preakness in nearly a century, cementing Jackson’s reputation as America’s king of wine and horses.

-

"Humes makes his charismatic subject's every venture vividly and intensely dramatic. This book will attract readers of diverse interests, from the law to wine-making to business to horse-racing." — Booklist

“A well-rounded, absorbing narrative of entrepreneurship, wine and the extraordinary man who made it all happen.” — Kirkus Review, starred

“Thoroughly engaging… this biography is as well-suited for those interested in people as those interested in wine.” — Minneapolis Star Tribune

“A classic American story—a man of the people becomes one of the greatest visionaries and qualitative titans the wine world has ever witnessed. Very highly recommended.” —Robert M. Parker, Jr., The Wine Advocate

“With dexterity and style, Edward Humes captures Jess Jackson, making his larger-than-life personality come alive and his rollercoaster story jump off the pages. A Man and His Mountain shows the inspiration, boundless energy, and tenacity that Jess Jackson embodied, but also the real man who was in ways like the rest of us, fallible and human. I expected a book about a winery, but what I got was an exciting, motiving, and epic journey of a man with laughs, tears, and surprises.” —Jennifer Simonetti-Bryan, master of wine, author of The One Minute Wine Master

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use