Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

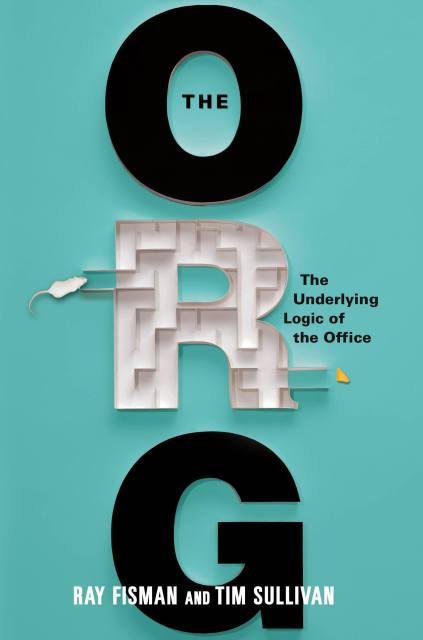

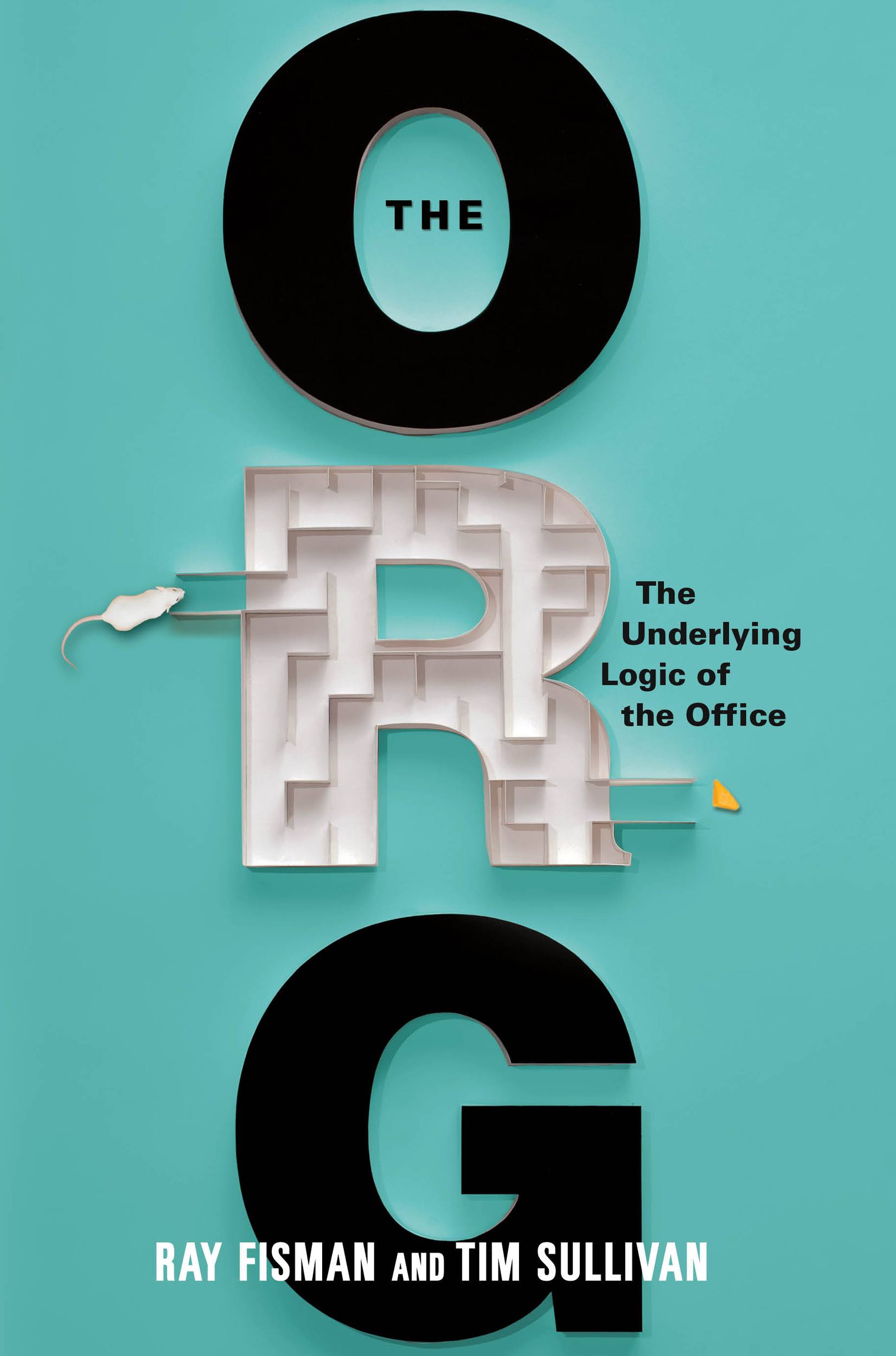

The Org

The Underlying Logic of the Office

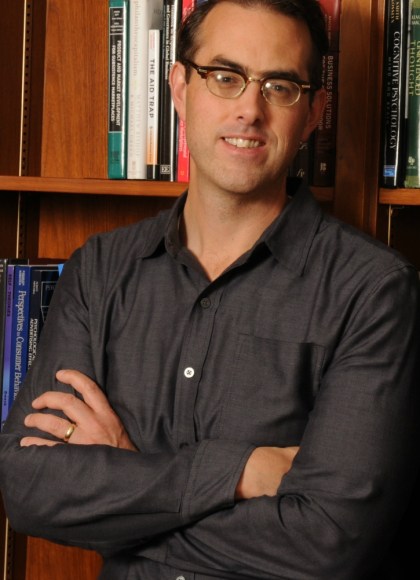

Contributors

By Ray Fisman

By Tim Sullivan

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $12.99 $16.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 8, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

We create organizations because we need to get a job done–something we couldn’t do alone–and join them because we’re inspired by their missions (and our paycheck). But once we’re inside, these organizations rarely feel inspirational. Instead, we’re often baffled by what we encounter: clueless managers, a lack of clear objectives, a seeming disregard for data, and the vast gulf between HR proclamations and our experience in the cubicle.

So where did it all go wrong?

In The Org, Ray Fisman and Tim Sullivan explain the tradeoffs that every organization faces, arguing that this everyday dysfunction is actually inherent to the very nature of orgs. The Org diagnoses the root causes of that malfunction, beginning with the economic logic of why organizations exist in the first place, then working its way up through the org’s structure from the lowly cubicle to the CEO’s office.

Woven throughout with fascinating case studies-including McDonald’s, al Qaeda, the Baltimore City Police Department, Procter and Gamble, the island nation of Samoa, and Google–The Org reveals why the give-and-take nature of organizations, while infuriating, nonetheless provides the best way to get the job done.

You’ll learn:

Looking at life behind the red tape, The Org shows why the path from workshop to corporate behemoth is pockmarked with tradeoffs and competing incentives, but above all, demonstrates why organizations are central to human achievement.

So where did it all go wrong?

In The Org, Ray Fisman and Tim Sullivan explain the tradeoffs that every organization faces, arguing that this everyday dysfunction is actually inherent to the very nature of orgs. The Org diagnoses the root causes of that malfunction, beginning with the economic logic of why organizations exist in the first place, then working its way up through the org’s structure from the lowly cubicle to the CEO’s office.

Woven throughout with fascinating case studies-including McDonald’s, al Qaeda, the Baltimore City Police Department, Procter and Gamble, the island nation of Samoa, and Google–The Org reveals why the give-and-take nature of organizations, while infuriating, nonetheless provides the best way to get the job done.

You’ll learn:

- The purpose of meetings and why they will never go away

- Why even members of al Qaeda are required to submit Travel & Expense reports

- What managers are good for

- How the army and other orgs balance marching in lockstep with fostering innovation

- Why it’s the hospital administration-not the heart surgeon-who is more likely to save your life

- That CEOs often spend over 80% of their time in meetings-and why that’s exactly where they should be (and why they get paid so much)

Looking at life behind the red tape, The Org shows why the path from workshop to corporate behemoth is pockmarked with tradeoffs and competing incentives, but above all, demonstrates why organizations are central to human achievement.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jan 8, 2013

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455517534

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use