By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

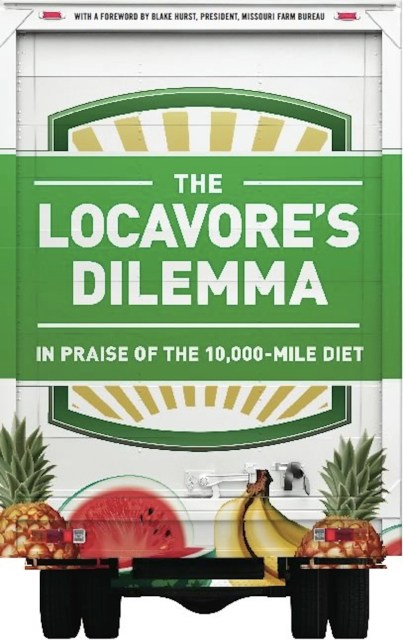

The Locavore’s Dilemma

In Praise of the 10,000-mile Diet

Contributors

By Hiroko Shimizu

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 5, 2012

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586489410

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $26.99 $30.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 5, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

But after a thorough review of the evidence, economic geographer Pierre Desrochers and policy analyst Hiroko Shimizu have concluded these claims are mistaken. In The Locavore’s Dilemma, they explain the history, science, and economics of food supply to reveal what locavores miss or misunderstand: the real environmental impacts of agricultural production; the drudgery of subsistence farming; and the essential role large-scale, industrial producers play in making food more available, varied, affordable, and nutritionally rich than ever before in history. At best, they show, locavorism is a well-meaning marketing fad among the world’s most privileged consumers. At worst, it constitutes a dangerous distraction from solving serious global food issues.

Deliberately provocative, but based on scrupulous research and incontrovertible scientific evidence, The Locavore’s Dilemma proves that:

Our modern food-supply chain is a superior alternative that has evolved through constant competition and ever-more-rigorous efficiency.

A world food chain characterized by free trade and the absence of agricultural subsidies would deliver lower prices and more variety in a manner that is both economically and environmentally more sustainable.

There is no need to feel guilty for not joining the locavores on their crusade. Eating globally, not only locally, is the way to save the planet.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use