By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

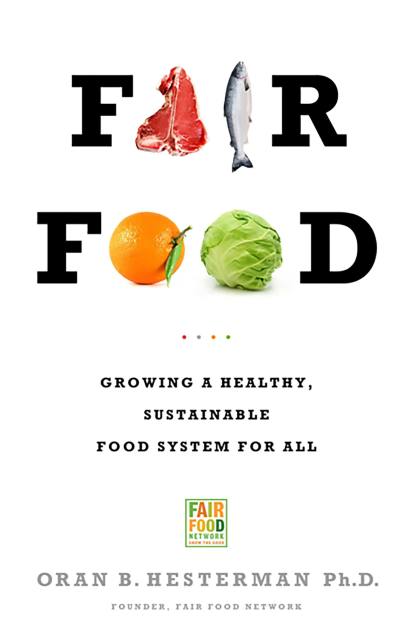

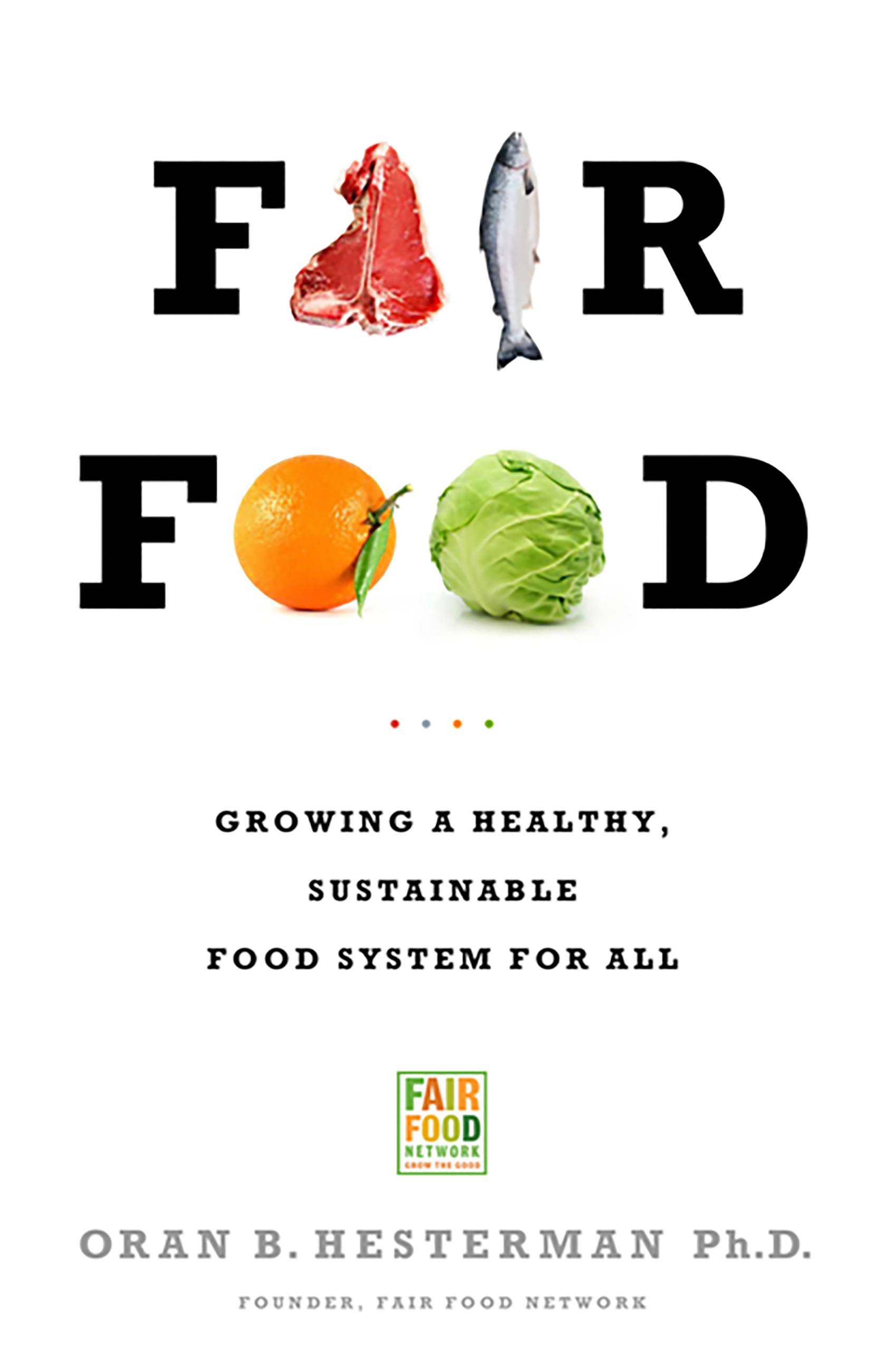

Fair Food

Growing a Healthy, Sustainable Food System for All

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 5, 2012

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610391023

Price

$15.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $19.99 CAD

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 5, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Fair Food is an enlightening and inspiring guide to changing not only what we eat, but how food is grown, packaged, delivered, marketed, and sold. Oran B. Hesterman shows how our system’s dysfunctions are unintended consequences of our emphasis on efficiency, centralization, higher yields, profit, and convenience — and defines the new principles, as well as the concrete steps, necessary to restructuring it. Along the way, he introduces people and organizations across the country who are already doing this work in a number of creative ways, from bringing fresh food to inner cities to fighting for farm workers’ rights to putting cows back on the pastures where they belong. He provides a wealth of practical information for readers who want to get more involved.

-

Civil Eats, June 1, 2011

“Unless you travel in food policy or agronomy circles, you probably haven't heard of Oran Hesterman. It's time you had. Hesterman, who runs the Ann Arbor, Michigan-based nonprofit Fair Food Network, has written a book that just might wake you up and get you to care about what's going on with the food you eat and how it gets to your table. Fair Food: Growing a Healthy, Sustainable Food System for All is what Hesterman is talking about, and I've got to admit, this reporter covering food news cracked open his book (which landed in bookstores yesterday) a tad wary. Would this highly educated and well-meaning agronomist-activist guy really offer anything new to the sustainable food conversation, I wondered, and more importantly, would he speak to regular people trying to feed their families in a tough economy and who might not understand the difference between grass and grain-fed (or why it matters)? Boy was I wrong and thrilled to stand corrected. Hesterman breaks free from a tradition of densely written, muddled prose intended for inside baseball players and instead speaks to us all, loud and clear.”

Ode Magazine, June 5, 2011

“Timely and inspiringly optimistic, Fair Food challenges and guides readers toward sustainability and health, for themselves and their communities.” -

Next American City website, August 24, 2011

“Fair Food covers a lot of territory, which also means it doesn't dive too deeply into any one subject. He touches on everything just enough to enhance the reader's understanding, but not enough to be hard hitting on many of the topics he cares most about. And that seems to be the point. This book is not intended to serve as an encyclopedia for the food movement, but more of a practical guide for concerned citizens and budding activists. It fails to conjure up some of the emotions similarly positioned books do, but doesn't leave you wondering “what can I do to change things?” Hesterman's goal for Fair Food is not to shock the masses, but to mobilize them to action."

-

Publishers Weekly, April 18, 2011

“Intended as a practical guide for community food activists who want to take the locavore movement across race, class, and city lines, this book illuminate ways in which consumers can become "engaged citizens." Especially important (and rare) is Hesterman's willingness to work constructively with corporate giants like Costco and the Kellogg Foundation….The dedication to social justice is clear, genuine, and logically argued as a food issue. A helpful and hefty final chapter of "Resources" provides readers with a comprehensive national listing of organizations to join, support, or replicate.” -

New York House Magazine, June, 27, 2011

“A must read for those who wish to go from conscious consumer to food activist.”

Edible Buffalo, Summer 2011

“Level the playing field with the next generations of Americans by adopting what Fair Food and Hesterman promotes. With Fair Food we will be able to apply a solution to one problem in our broken food system at a time.”

New York Times (Business Day), June 4, 2011

"[Hesterman] displays a wide-ranging knowledge of production, consumption, natural resources and public policy. He also writes about reform efforts with contagious energy and palpable authority...this is an important, accessible book on a crucial subject. Food for thought and action."

Serious Eats, July 29, 2011

“Hesterman's upbeat outlook and gentle push toward activism inspired me to further my own engagement. His book is one of the best I've read on how we as individuals can be involved in the future of America's food system."

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use