Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

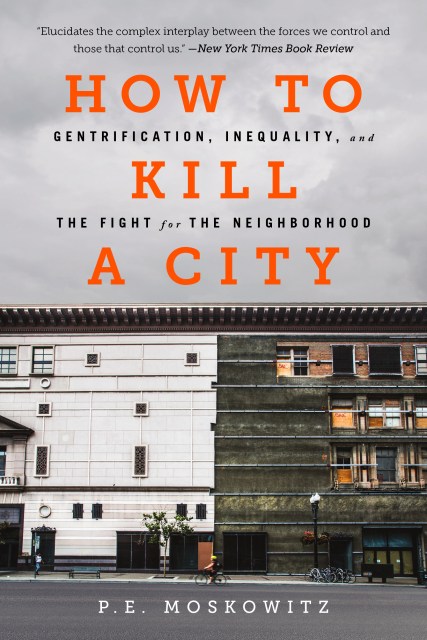

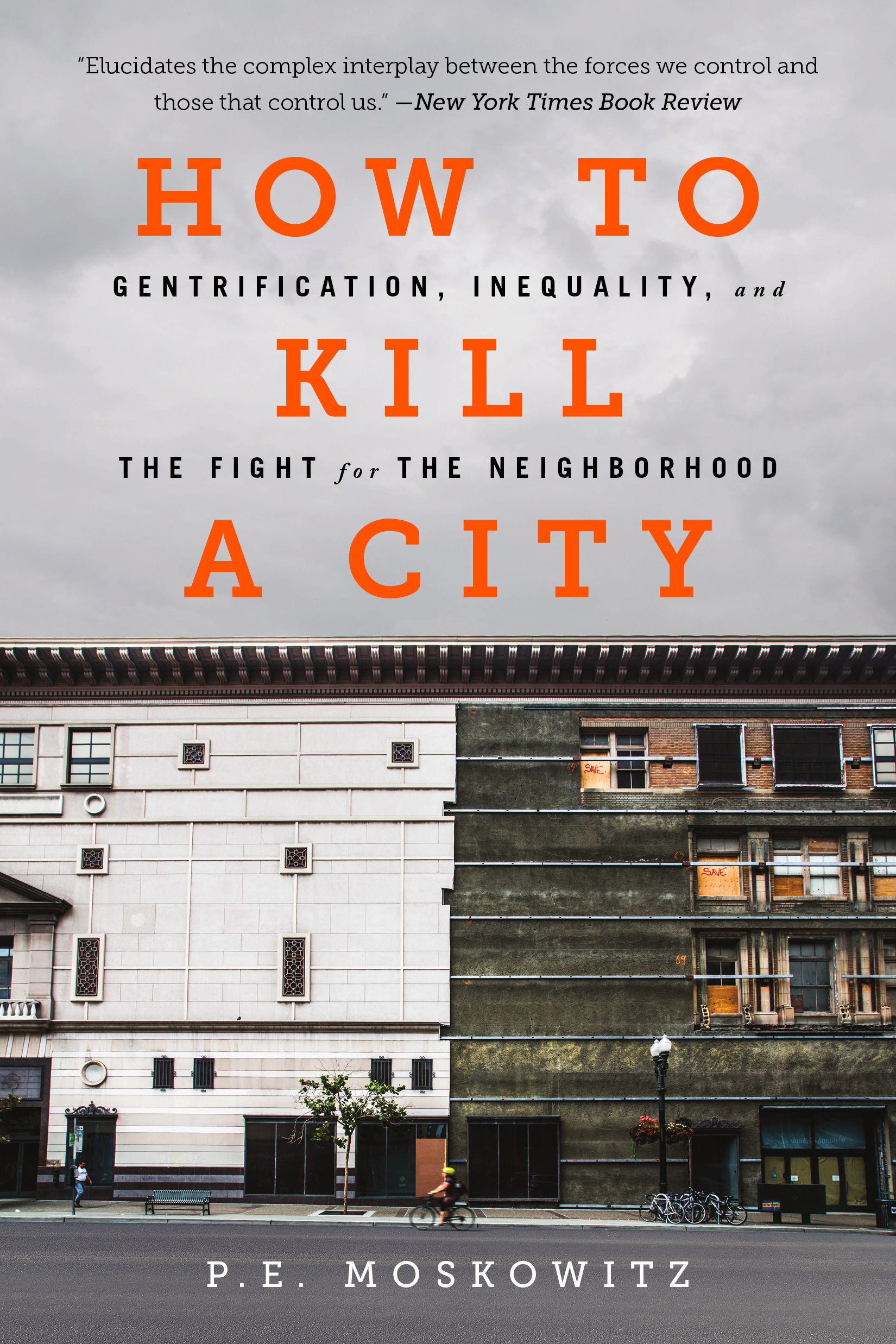

How to Kill a City

Gentrification, Inequality, and the Fight for the Neighborhood

Contributors

By PE Moskowitz

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 7, 2017

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568585246

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback (Revised) $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 7, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The term gentrification has become a buzzword to describe the changes in urban neighborhoods across the country, but we don’t realize just how threatening it is. It means more than the arrival of trendy shops, much-maligned hipsters, and expensive lattes. The very future of American cities as vibrant, equitable spaces hangs in the balance.

P. E. Moskowitz’s How to Kill a City takes readers from the kitchen tables of hurting families who can no longer afford their homes to the corporate boardrooms and political backrooms where destructive housing policies are devised. Along the way, Moskowitz uncovers the massive, systemic forces behind gentrification in New Orleans, Detroit, San Francisco, and New York. In the new preface, Moskowitz stresses just how little has changed in those same cities and how the problems of gentrification are proliferating throughout America.

The deceptively simple question of who can and cannot afford to pay the rent goes to the heart of America’s crises of race and inequality. A vigorous, hard-hitting exposé, How to Kill a City reveals who holds power in our cities and how we can get it back.

-

"[An] exacting look at gentrification in New Orleans, Detroit, San Francisco and New York, exposing how large institutions-goverments, businesses, foundations-influence street-level processes that might appear as organic as the coffee shop's dark roast. ... How to Kill a City elucidates the complex interplay between the forces we control and those that control us."New York Times Book Review

-

"Moskowitz is a talented and impassioned writer...They poke, prod and listen. They find holes in official stories and gifted storytellers among people who have been steamrolled."San Francisco Chronicle

-

"Movingly conveys [gentrification's] emotional and sometimes tragic toll as they highlight its stark racial realities in Detroit, San Francisco, New York and New Orleans."Washington Post

-

"When it comes to housing and urban development, as with other aspects of American life, Moskowitz makes clear that the heft of one's purse and the color of one's skin are determinative. How to Kill a City is an indictment of a system that places making a home for capital above making homes for people."Santa Barbara Independent

-

"Gentrification takes a community's personal tragedy, loss and destruction, and monetizes it. Understanding how this happens, and how individuals may unwittingly find themselves a part of it is what makes Moskowitz's book so important. It isn't a lesson about what happened, it's a warning about what is happening now."Truthout

-

"How to Kill a City is a convincing and persuasive argument that the U.S. has a serious problem with affordable housing that is not going away any time soon."Booklist

-

"Moskowitz...pulls no punches in his depiction of gentrification...They paint a vivid and grim picture of the future of American cities."Kirkus

-

"A forceful critique of gentrification and its impact on disempowered members of American society."Library Journal

-

"A fascinating analysis of late-stage gentrification in which corporate control of cities renders them uninhabitable to most people. Showing how gentrifiers exploit 'someone else's loss' as a consequence of long histories of racist policy, Peter Moskowitz calls for a global movement against this 'new form of segregation,' defining housing as a human right rooted in community instead of real estate profit."Sarah Schulman, author of Gentrification of the Mind and The Cosmopolitans

-

"Peter Moskowitz offers a smartly written and fiercely logical indictment of city governments for selling out longtime residents to aggressive developers and rich investors, and calling it growth. This book is a wake-up call to communities to say no to state-sponsored gentrification and join together to resist their own demise."Sharon Zukin, author of Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places