Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

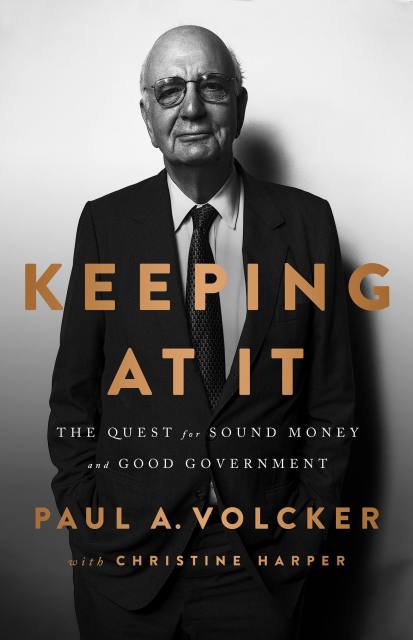

Keeping At It

The Quest for Sound Money and Good Government

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 30, 2018

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541788299

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 30, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

As chairman of the Federal Reserve (1979-1987), Paul Volcker slayed the inflation dragon that was consuming the American economy and restored the world’s faith in central bankers. That extraordinary feat was just one pivotal episode in a decades-long career serving six presidents.

Told with wit, humor, and down-to-earth erudition, the narrative of Volcker’s career illuminates the changes that have taken place in American life, government, and the economy since World War II. He vibrantly illustrates the crises he managed alongside the world’s leading politicians, central bankers, and financiers. Yet he first found his model for competent and ethical governance in his father, the town manager of Teaneck, NJ, who instilled Volcker’s dedication to absolute integrity and his “three verities” of stable prices, sound finance, and good government.