By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

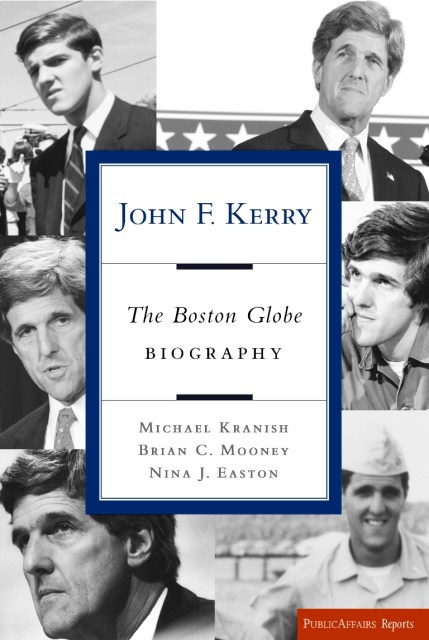

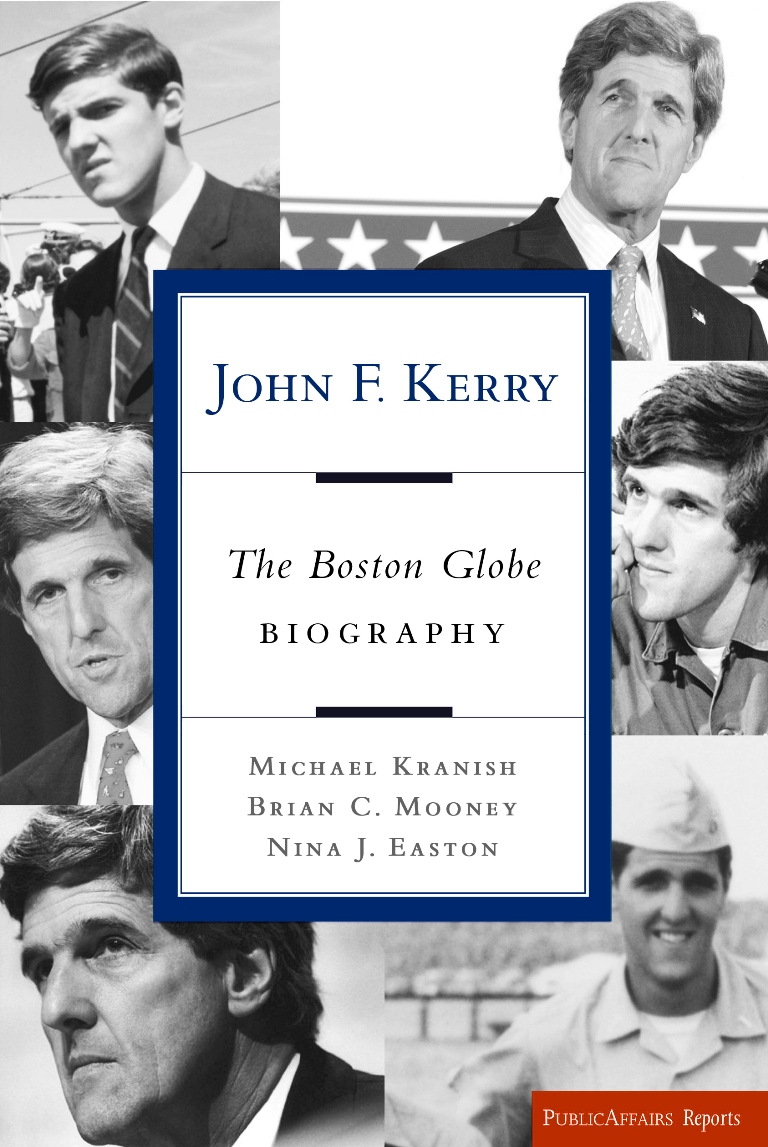

John F. Kerry

The Boston Globe Biography

Contributors

By Brian Mooney

By Nina J. Easton

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 5, 2013

- Page Count

- 488 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610393379

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 5, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The outlines of John Kerry’s life are familiar: A decorated Vietnam veteran who became an influential, if unlikely, anti-war protester. A lanky 60-year-old who quenches his thirst for danger with high-speed kiteboarding, windsurfing, piloting, motorcycling, and, in some cases, driving. A senator with a reputation as an investigator and foreign policy expert. A man married to one of the richest women in America. But beyond this broad picture, Kerry is something of a mystery to the public, largely because of a complex yet riveting personal and professional history outlined in this book.

John F. Kerry: The Complete Biography, the first full and in-depth book about the candidate’s life, is based on a highly regarded series on Kerry published in the Boston Globe, plus years of additional reporting. It will explore his background, his service in the military (including significant experiences omitted from Douglas Brinkley’s bestselling Tour of Duty), his early legal and political career, his legislative record and the remarkable turnaround in his political fortunes during the 2004 election cycle. This incisive, frank look at Kerry’s life, and at his strengths and liabilities, is important reading for anyone interested in the presidential campaign.

-

"An extensive, and in my view, very fine piece of work."—Brit Hume, Fox News Channel

"Kerry campaign... is portrayed in this book for the inquisitive voter or political junkie."—Campaigns & Elections

"The conscientious research in this book reveals that [these] reporters ... were out to get the facts."—Washington Post

“Energetically fleshes out the details of Mr. Kerry's life and career…. [A] fascinating portrait.”—The New York Times

"A ready guide to the Democratic nominee."—National Review

"An extensive, well-documented overview"—Louisville Courier-Journal

"Excellent and thoroughly researched... likely to become one of the most authoritative sources on the candidate."—Library Journal

"Exhaustive, textured ... to know who ... Kerry is and what kind of president he might be, this is the book"—Newhouse News Service

"Quick read ... gives a ... three-dimensional character... [the authors] have left enough new in there to keep you turning the page."—ABCNews.com

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use