By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

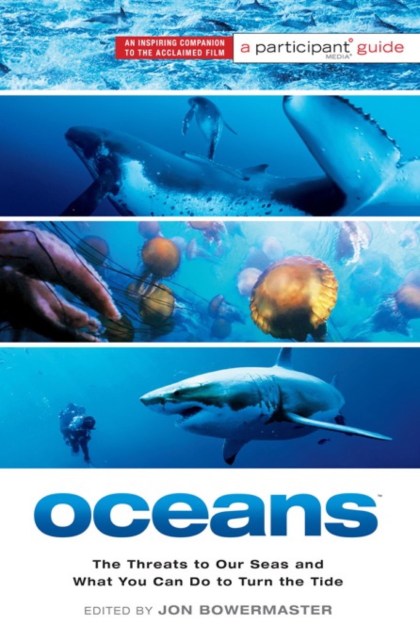

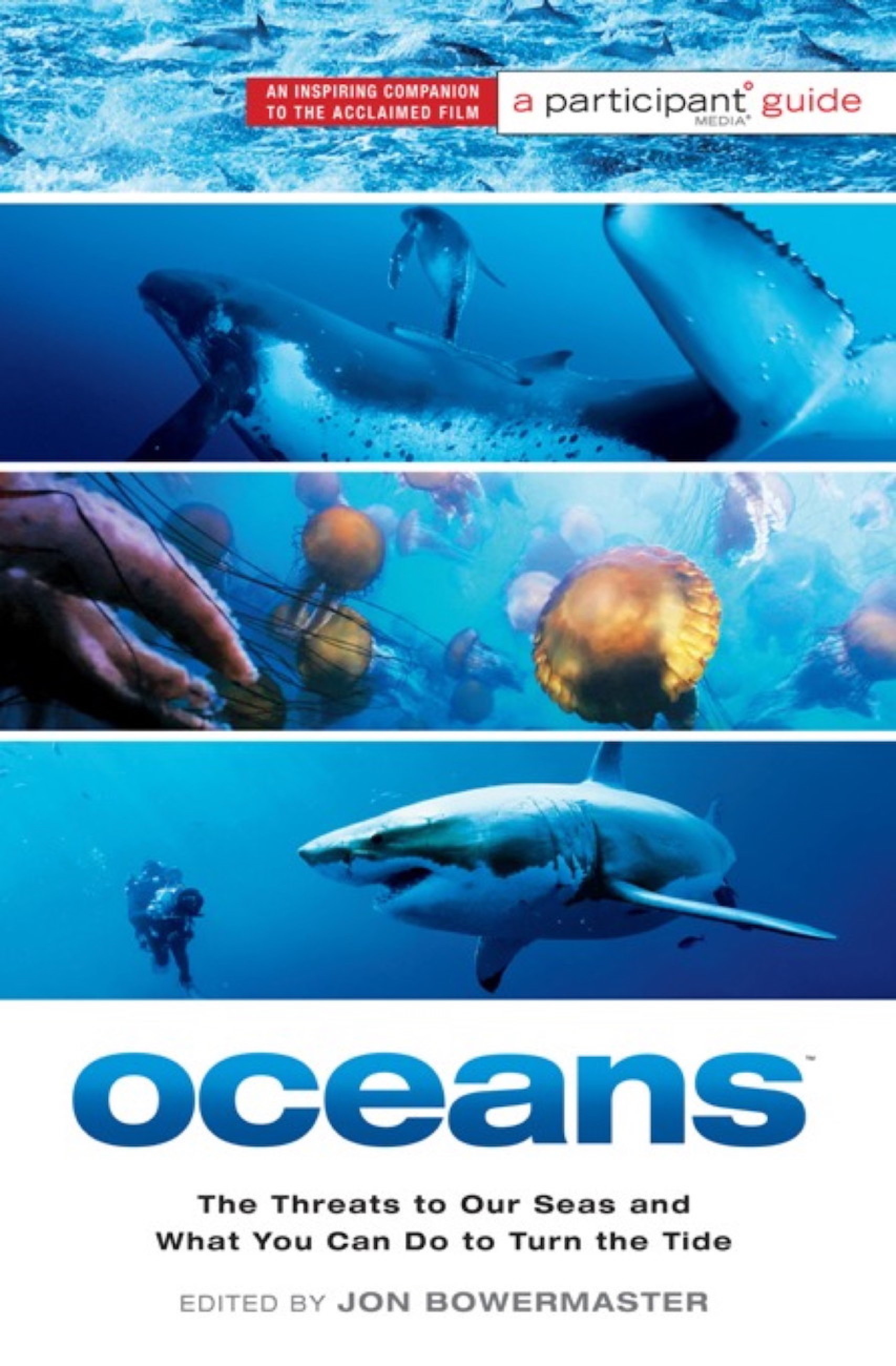

Oceans

The Threats to Our Seas and What You Can Do to Turn the Tide

Contributors

Edited by Participant

Edited by Jon Bowermaster

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 23, 2010

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586488420

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook (Media Tie-In) $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback (Media Tie-In) $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 23, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

More than 75 percent of the globe is covered by the oceans. It is sometimes difficult to understand why it is called Planet Earth rather than Planet Ocean. Since half the world’s human population lives within a stone’s throw of an ocean coastline, the oceans’ health is increasingly important. Rich with resources and potential — as a source of renewable energy, new drugs, drinking water — for years we have treated them as both infinite and undamageable. But they are not.

Over-fishing, climate change, pollution, acidification, and more have put the world’s oceans and marine life at great risk.

Oceans gathers some of the most insightful visionaries, explorers, and ocean lovers — marine biologists, politicians, environmentalists, fishermen, sportsmen, deep divers, and more — in a unique anthology, in which each speaks to a unique aspect of our world’s most dimly understood dimension.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use