By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

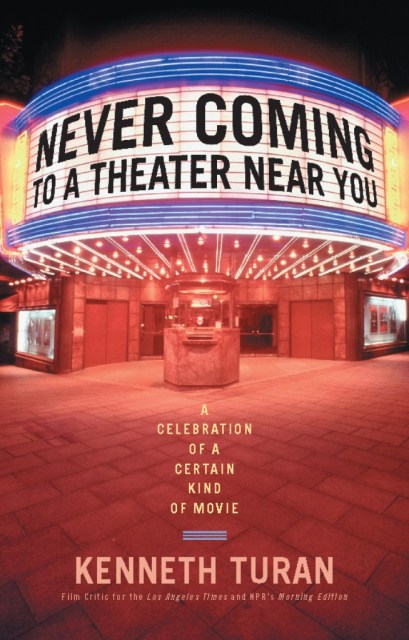

Never Coming to a Theater Near You

A Celebration of a Certain Kind of Movie

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 1, 2005

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786723942

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 1, 2005. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This selection of renowned film critic Kenneth Turan’s absorbing and illuminating reviews, now revised and updated to factor in the tests of time, point viewers toward the films they can’t quite remember, but should not miss.

Moviegoers know they can trust Turan’s impeccable taste. His eclectic selection represents the kind of sophisticated, adult, and entertaining films intelligent viewers are hungry for. More importantly, Turan shows readers what makes these unusual films so great, revealing how talented filmmakers and actors have managed to create the wonderful highs we experience in front of the silver screen.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use