Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

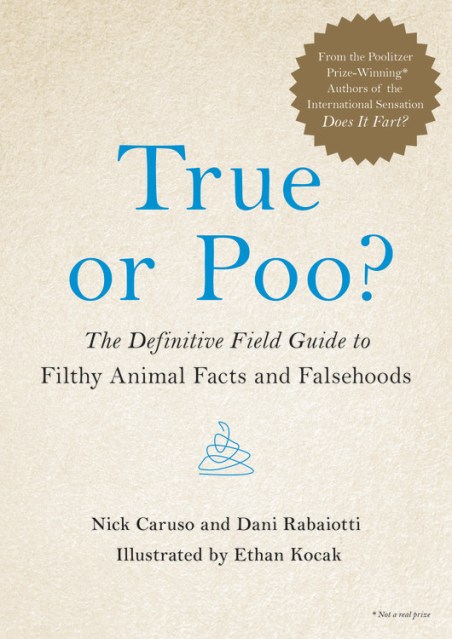

True or Poo?

The Definitive Field Guide to Filthy Animal Facts and Falsehoods

Contributors

By Nick Caruso

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 23, 2018

- Page Count

- 160 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316528122

Price

$16.00Price

$21.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $16.00 $21.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $14.98

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 23, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

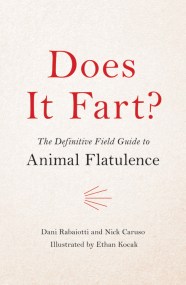

After Does It Fart? comes Number Two…a fully illustrated compendium of animal facts and falsehoods — the more repulsive the better.

Do komodo dragons have toxic slobber? Is it true that a scorpion that sheds its tail dies of constipation? Speaking of poo, do rabbits really have a habit of, err, eating their own? And can you really get high from licking toads, or is that…fake newts?

The answers to all these questions and more can be found in True or Poo?, a manual for disgusting and one-upping your friends and enemies for years to come.

Genre:

Series:

-

"A very necessary book."New York Post

-

"A book everyone can enjoy."Cheezburger

-

"Appropriately titled."BuzzFeed

-

"The only book on animal flatulence you'll ever need."The Telegraph (UK)

-

"Answers the important questions."Popular Mechanics

-

"It's time to embrace both your scientific curiosity and your inner 10-year-old."CNet

-

"The book is jam-packed with Fart Facts, giving time to the farters, the non-farters, and those where the fart-jury is still out.... Does It Fart? is the sort of book that reaches everyone."ScientificAmerican.com

-

"The topic of flatulence is richer and more varied than readers might expect.... Cheeky illustrations by Ethan Kocak add to the book's general irreverence... The book now occupies a place of honor in my house, next to the toilet, where it is always on call to satisfy the curiosity of my lucky guests when they need a bit of bathroom reading."Katie L. Burke, American Scientist

-

"Does It Fart? clearly makes the perfect gift for animal lovers, science geeks, and fart-obsessed teenage boys. Sniff one out for the special stinker in your life now."People.com

-

Praise for True or Poo?Mental Floss

"This breezy read will give you numerous unexpected insights into the animal kingdom.... With whimsical illustrations and an entire section on animal digestion and excretion, it's an educational book for the whole family."