Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

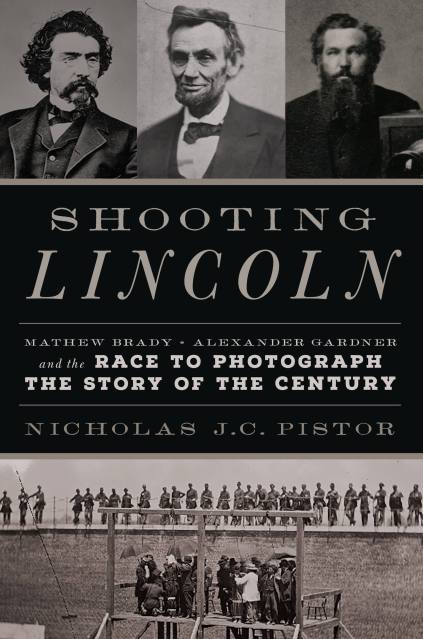

Shooting Lincoln

Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardner, and the Race to Photograph the Story of the Century

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 19, 2017

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306824692

Price

$28.00Price

$36.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 19, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner were the new media moguls of their day. With their photographs they brought the Civil War — and all of its terrible suffering — into Northern living rooms. By the end of the war, they were locked in fierce competition.

And when the biggest story of the century happened–the assassination of Abraham Lincoln–their paparazzi-like competition intensified. Brady, nearly blind and hoping to rekindle his wartime photographic magic, and Gardner, his former understudy, raced against each other to the theater where Lincoln was shot, to the autopsy table where Booth was identified, and to the gallows where the conspirators were hanged. Whoever could take the most sensational — or ghastly — photograph would achieve lasting camera-lens fame.

Compelling and riveting, Shooting Lincoln tells the astonishing, behind-the-photographs story of these two media pioneers who raced to “shoot” the late president and the condemned conspirators. The photos they took electrified the country, fed America’s growing appetite for tabloid-style sensationalism in the news, and built the media we know today.

-

"Shooting Lincoln is a fascinating look at a war within a war, when two rival photographers battled to chronicle the Civil War. Nicholas Pistor's gripping saga carries the reader onto battlefields and alongside the hangman's noose while chronicling the birth of modern photojournalism. A fascinating read that sharpens our focus on how much that war remains relevant today."--Scott McGaugh, author of the New York Times bestseller Surgeon in Blue: Jonathan Letterman, the Civil War Doctor Who Pioneered Battlefield Care

-

"Nicholas Pistor has written an engaging account of Civil War-era photographers Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner and the birth of American news photography. Pistor's riveting narrative of Abraham Lincoln's assassination and its aftermath is by itself well worth the read."--Joseph Wheelan, author of Terrible Swift Sword and Their Last Full Measure

-

"A remarkable history of Civil War era journalism."Midwest Book Review

-

"A gripping read...[written with] urgency and flair."Wall Street Journal

-

"An engaging read."Washington Independent Review of Books

-

"Pistor makes a convincing case that the efforts of Brady and Gardner consciously and often heroically documented history."Santa Fe New Mexican