By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

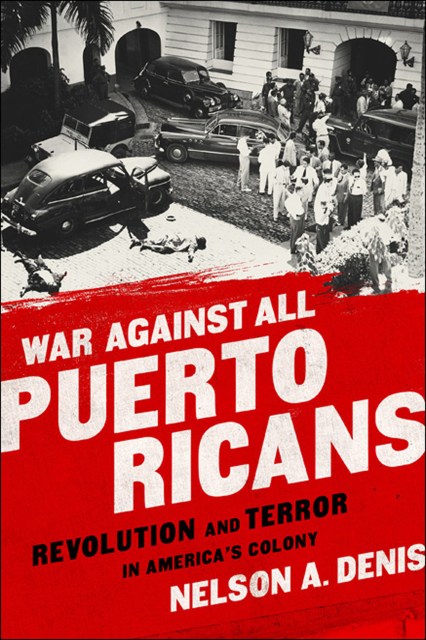

War Against All Puerto Ricans

Revolution and Terror in America's Colony

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 7, 2015

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568585024

Price

$11.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 7, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Nelson A. Denis tells this powerful story through the controversial life of Pedro Albizu Campos, who served as the president of the Nationalist Party. A lawyer, chemical engineer, and the first Puerto Rican to graduate from Harvard Law School, Albizu Campos was imprisoned for twenty-five years and died under mysterious circumstances. By tracing his life and death, Denis shows how the journey of Albizu Campos is part of a larger story of Puerto Rico and US colonialism.

Through oral histories, personal interviews, eyewitness accounts, congressional testimony, and recently declassified FBI files, War Against All Puerto Ricans tells the story of a forgotten revolution and its context in Puerto Rico’s history, from the US invasion in 1898 to the modern-day struggle for self-determination. Denis provides an unflinching account of the gunfights, prison riots, political intrigue, FBI and CIA covert activity, and mass hysteria that accompanied this tumultuous period in Puerto Rican history.

-

“Sometime in the not-too distant future, we will resolve the relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico. To understand where we are going, we must know our past—both good and bad. War Against All Puerto Ricans fills an important gap in that historical understanding. It is a book that every student of the US–Puerto Rico relationship should read.”Congressman José Serrano

-

"[Nelson Denis] provides scathing insights into Washington's response to Albizu Campos's nationalist party and its violent revolution in 1950 that still has broad implications...his perspective of largely overlooked history could not be more timely."The New York Times

-

"War Against All Puerto Ricans is a fascinating read...mind-blowing...women were sterilized, people were tortured, cities were bombed by US planes...A lot of Americans will learn a great deal from reading it. I know I did."Jerome McDonald, WBEZ Worldview

-

"In searing and well-researched prose, former New York assemblyman and El Diario editorial director Denis covers a much-neglected side of U.S. imperialist and colonial practice in Puerto Rico...The historical account he adeptly weaves unabashedly reveals the government's racist and often predatory actions toward its Caribbean colony...This timely, eye-opening title is as much a must-read as Juan Gonzalez's Harvest of Empire."Shelley Diaz, Library Journal

-

“Reveals the true face of American imperialism in its own backyard…Denis's meticulous research reveals an often overlooked element of American history and provides context to the current status of Puerto Rico as a U.S. territory.”Publishers Weekly

-

"A meticulous and riveting account of the decades-long clash between the Puerto Rican independence movement, led by Pedro Albizu Campos, and the commonwealth's U.S.-appointed stewards, national police force, the FBI and, ultimately, the U.S. Army"Ray Mondell, New York Daily News

-

"A pointed, relentless chronicle of a despicable part of past American foreign policy."Kirkus Reviews

-

"An enlightening and engaging read...a must-read for anyone interested in learning more about Puerto Rico. Denis provides a more detailed account, thanks to exclusive interviews conducted over a span of decades, as well as thousands of public records, including recently de-classified FBI documents."Andre Lee Muñiz, La Respuesta

-

"A patient, calibrated, fully-researched study of the mendacious, hypocritical way the United States treats its Caribbean colony, castrating its leadership, bombarding its villages, experimenting biologically with its population. Puerto Rico is, in a word, el calabozo. Denis knows the truth first-hand and refuses to sugarcoat it.”Ilan Stavans, author of Spanglish: The Making of a New American Language

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use