Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

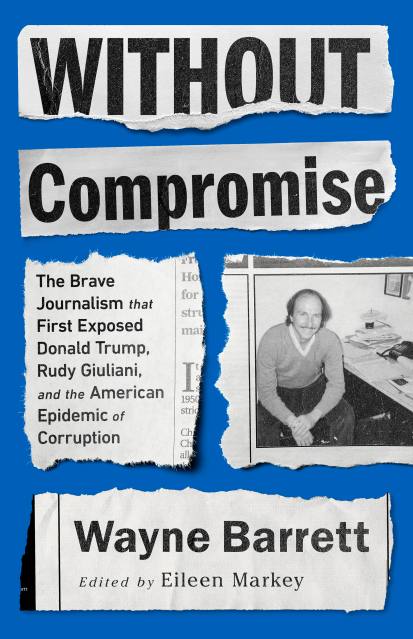

Without Compromise

The Brave Journalism that First Exposed Donald Trump, Rudy Giuliani, and the American Epidemic of Corruption

Contributors

Edited by Eileen Markey

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 29, 2020

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781645036531

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 29, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

With piercing moral clarity and exacting rigor, Wayne Barrett tracked political corruption in the pages of the Village Voice fact by fact, document by document for 40 years. The first to report on the scams and crooked deals that fueled the rise of Donald Trump in 1979, Barrett went on to expose the shady dealings of small-time slum lords and powerful New York City politicians alike, from Ed Koch to Rudy Giuliani to Michael Bloomberg.

Without Compromise is the first anthology of Barrett’s investigative work, accompanied by essays from colleagues and those he trained. In an age of lies, fog, and propaganda, when the profession of journalism is degraded by the White House and the industry is under financial threat, Barrett reminds us that facts, when clearly accumulated, are our best defense of democracy.

Featuring essays by:

Joe Conason

Kim Phillips-Fein

Errol Louis

Gerson Borrero

Tom Robbins

Tracie McMillan

Peter Noel

Adam Fifield

Jarrett Murphy

Andrea Bernstein

Jennifer Gonnerman

Mac Barrett

Genre:

-

"As Donald Trump rose to power no journalist busted him earlier or better than the late investigative reporter Wayne Barrett, whose indispensable work is gathered in Without Compromise. Barrett's pieces provide an x-ray into Trump's soul, and into the civic corruption that fueled his rise. These stories are essential reading, alive with fresh insights and information illuminating today's politics, and remind us that rigorous journalism is still democracy's best defense."Jane Mayer, author of Dark Money

-

"An instantly classic collection by one of the greatest reporters New York ever produced, and one of the greatest of his era. Few could combine righteous fury with dogged attention to detail like Barrett. This collection is a treasure and (somewhat maddeningly) a reminder that the fools, crooks, and wannabe strongmen that have our republic dangling over a precipice have been this way for a long, long time."Chris Hayes, author of A Colony in a Nation

-

"These pages bring Wayne Barrett back to life in all his investigative glory, his moral clarity, his righteous rage. Barrett was prescient, not just about Donald Trump and Rudy Giuliani, but also about how, time and time again, individuals and institutions would fail to rein in the greed of those who feed off the public trough and to address the racism that undergirds both public policy and private behavior. Wayne Barrett's life and work continue to inspire, especially at a time when truth and facts are under siege. He had a mantra: 'The job of our profession is discovery, not dissertation.' Journalists are paid to tell the truth, he said, and that he did, no matter who, no matter what."Sheila Coronel, dean of academic affairs and director, Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism, Columbia Journalism School