Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

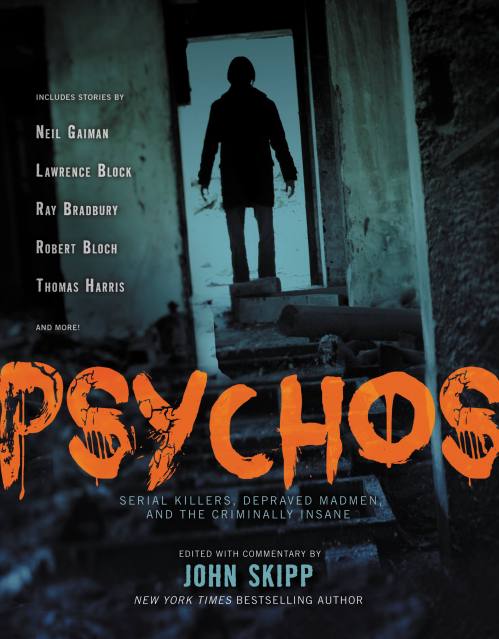

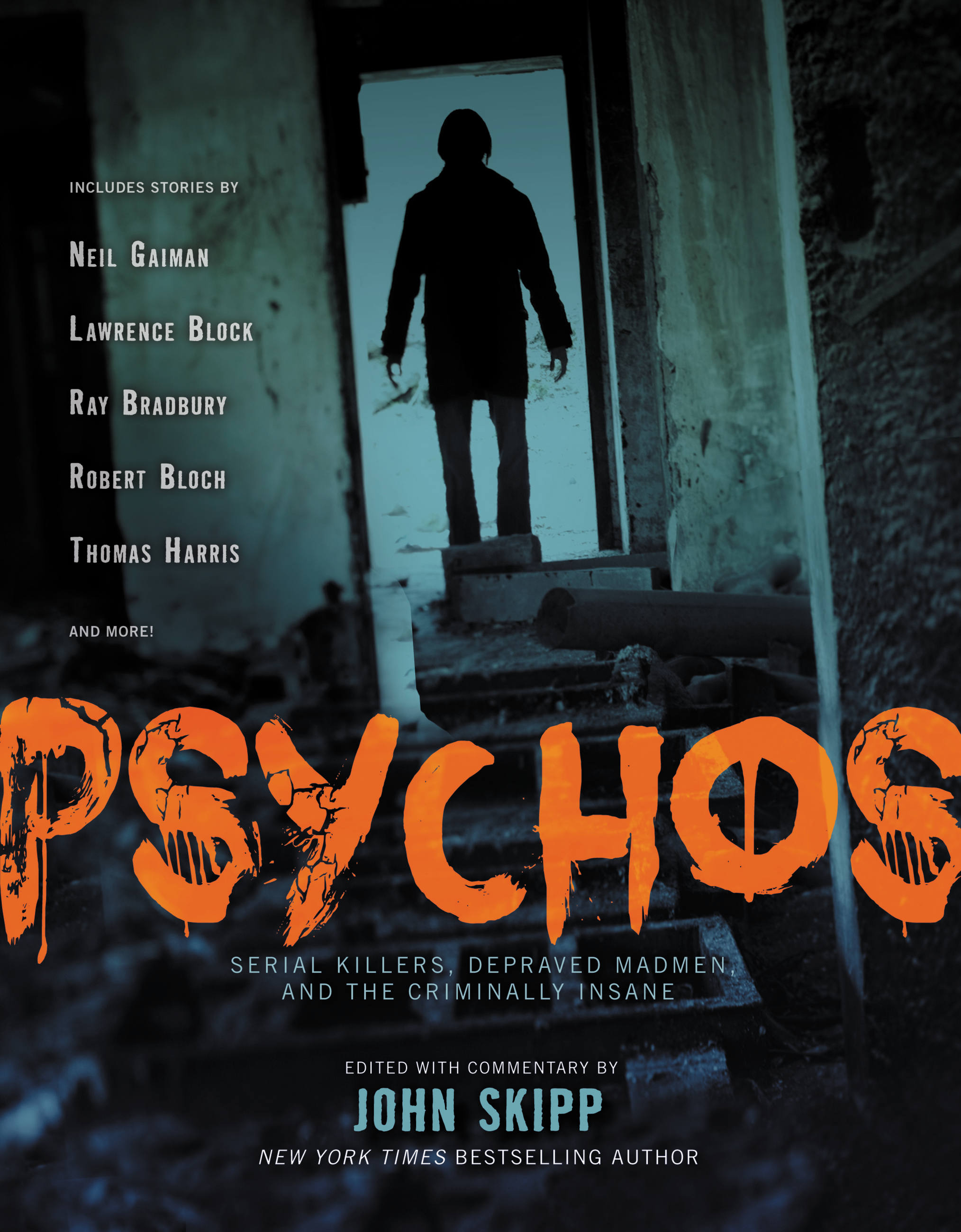

Psychos

Serial Killers, Depraved Madmen, and the Criminally Insane

Contributors

Contributions by Neil Gaiman

By John Skipp

Contributions by Lawrence Block

Contributions by Ray Bradbury

Contributions by Joe R. Lansdale

Contributions by Edgar Allan Poe

Contributions by Jim Shepard

Contributions by Richard Connell

Contributions by Amelia Beamer

Contributions by Joan Aiken

Contributions by Laura Lee Bahr

Contributions by William Gay

Contributions by Jack Ketchum

Contributions by Mercedes M. Yardley

Contributions by Steve Rasnic Tem

Contributions by David J. Schow

Contributions by Leah Mann

Contributions by Kevin L. Donihe

Contributions by Leslianne Wilder

Contributions by Norman Partridge

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $12.99 $15.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 25, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From Hannibal Lecter (The Silence of the Lambs) to Patrick Bateman (American Psycho), stories of serial killers and psychos loom large and menacing in our collective psyche. Tales of their grisly conquests have kept us cowering under the covers, but still turning the pages.

Psychos is the first book to collect in a single volume the scariest and most well-crafted fictional works about these deranged killers. Some of the stories are classics, the best that the genre has to offer, by renowned writers such as Neil Gaiman, Amelia Beamer, Robert Bloch, and Thomas Harris. Other selections are from the latest and most promising crop of new authors.

John Skipp, who is also the editor of Zombies, Demons and Werewolves and Shapeshifters, provides fascinating insight, through two nonfiction essays, into our insatiable obsession with serial killers and how these madmen are portrayed in popular culture. Resources at the end of the book includes lists of the genre’s best long-form fiction, movies, websites, and writers.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 25, 2012

- Page Count

- 608 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9781603763172

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use